Ben Franklin May Be Responsible for Bringing Tofu to America

How a letter of 1770 may have ushered the Chinese staple into the New World

:focal(2143x1408:2144x1409)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/5f/7f5f78d5-f722-46bf-85e2-da09ae47fc1b/tofu4.jpg)

When you picture Benjamin Franklin, what do you see? A lovable mad scientist flying a kite in the rain, perhaps, or a shrewd political strategist haggling at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Maybe you imagine Franklin schmoozing with the French, brokering deals, or hurriedly setting type in the offices of the Pennsylvania Gazette. What you likely do not envision is Franklin the gardening whiz and gourmet, writing excitedly from London on the subject of a mysterious Chinese “cheese” called “tau-fu.”

The letter in question, preserved for posterity by The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, dates to January 1770, and was addressed to Franklin’s Philadelphia bosom buddy John Bartram. “I send some dried Pease, highly esteemed here as the best for making pease soup,” Franklin wrote, “and also some Chinese Garavances, with Father Navaretta’s account of the universal use of a cheese made of them, in China…” This unassuming letter, one of countless thousands to make its way across the Atlantic in the years leading up to the Revolutionary War, is the earliest known description of tofu—the Chinese “cheese” in question—to reach American soil.

Together, Bartram and Franklin had founded the American Philosophical Society in 1743, and both were prominent members of the intellectually minded community betterment club known as the Junto, which Franklin had created in 1727 at 21 years of age. Living in the same city, the two friends had no need to write each other letters. But once Franklin’s political maneuvering brought him to England, a line of correspondence quickly opened up. In brief, amiable messages, the two thinkers discussed whatever fresh projects were on their minds. More often than not, these projects had a horticultural bent.

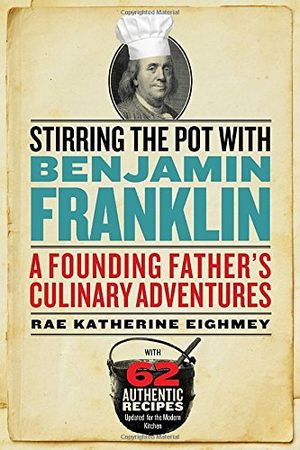

Bartram had his own claims to fame in colonial America. Among other things (including an avid amateur fossil hunter), he was “America’s premier botanist,” says Rae Katherine Eighmey, author of the recently released colonial kitchen odyssey Stirring the Pot With Benjamin Franklin. “He tromped—literally tromped—from Canada to Florida seeking new and unusual plants, which he would then package up and send to people in England.” And not just anyone, Eighmey says, but “the social folks, and the scientifically inclined people”—the cream of the crop.

Both Bartram and Franklin forged their wide-ranging social connections with the aid an eminent London patron named Peter Collinson, who would eventually secure Franklin his place in England’s Royal Society. It was via Collinson’s network of European intelligentsia that the two friends learned of and shared botanical discoveries and specimens.

Stirring the Pot with Benjamin Franklin: A Founding Father's Culinary Adventures

Stirring the Pot with Benjamin Franklin conveys all of Franklin's culinary adventures, demonstrating that Franklin's love of food shaped not only his life but also the character of the young nation he helped build.

There was an element of curiosity behind the worldwide interest in novel agriculture, but more important, says historian Caroline Winterer, author of American Enlightenments, was the element of necessity. “There’s just not enough food,” Winterer says, “and there’s no refrigeration until the middle of the 19th century, so a lot of food perishes before it reaches its destination.” The solution? Import seeds from afar, then grow locally.

Bartram’s distinguished recipients would grow his seeds in their personal greenhouses, Eighmey says, and pen reciprocal letters back to the States reporting on results—often with enclosures of their own. “Everybody’s sending stuff back and forth.”

Winterer sees Franklin and Bartram’s epistolary relationship as part of a broader picture of agricultural fervor in the 18th century, what she describes as “a larger, global seed network.”

“This is a great age of food transport,” Winterer says. “Potatoes, corn, all kinds of American plants are brought into Europe.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/76/eb76d86a-16b8-4fb9-a14f-90dbfa2993ac/tofu2.jpg)

The transfer of agricultural knowledge didn’t always begin in the New World, however, as evidenced by the writing of Dominican friar Fernandez Navarrete, whom Franklin cites (as “Father Navaretta”) in a 1770 missive to Bartram. Navarrete, visiting Asia, “learned about all the ‘strange things people in China eat,’” Winterer explains, quoting the mendicant’s logs, and published his discoveries in Spanish in 1676. Among these was a method for preparing a popular Chinese foodstuff, which Navaretta termed “teu-fu.” Franklin presumably came across the reference in translated form—the friar’s logs were republished multiple times in English in the early 18th century.

“He basically says they’re making cheeses out of what he calls kidney beans—what we would call soybeans,” Winterer says.

This “cheese” verbiage is preserved in Franklin’s letter, which calls Bartram’s attention to Navarrete’s field research as well as a recipe Franklin managed to procure from a British buttonmaker buddy called “Mr. Flint.” Franklin included with his written note some “Chinese Garavances,” by which he also undoubtedly meant “soybeans” (“garavance” is an Anglicization of the Spanish “garbanzo”). In addition, he enclosed rhubarb seeds for Bartram to play with, and dry peas for making soup.

What Bartram did with Franklin’s information is uncertain. “I don’t think anyone would know whether they actually themselves made the tofu,” says Winterer—the historical record simply isn’t clear enough to draw such conclusions definitively. “But they’re clearly aware that there is tofu.”

Whether or not Bartram produced the first-ever American tofu, Franklin’s letter is a fascinating snapshot of the global 18th-century agriculture boom that paved the way for our modern food economy.

“Today,” Winterer says, “[mailed plant matter] would be stopped ruthlessly at the border. But back then it was like a sieve. ‘Try this! Try planting this in your garden. See what happens.’” This spirit of experimentation and collaboration ultimately led to the spread of exotic crops and foods all over the globe. “The result,” Winterer concludes, “is the world we have today.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)