The Women Who Fried Donuts and Dodged Bombs on the Front Lines of WWI

Even if they had to use shell casings as rolling pins, the donuts still got made

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e5/d2/e5d2244f-bdf8-4f46-b6ea-d111cd091e2f/donut_girl_2.jpg)

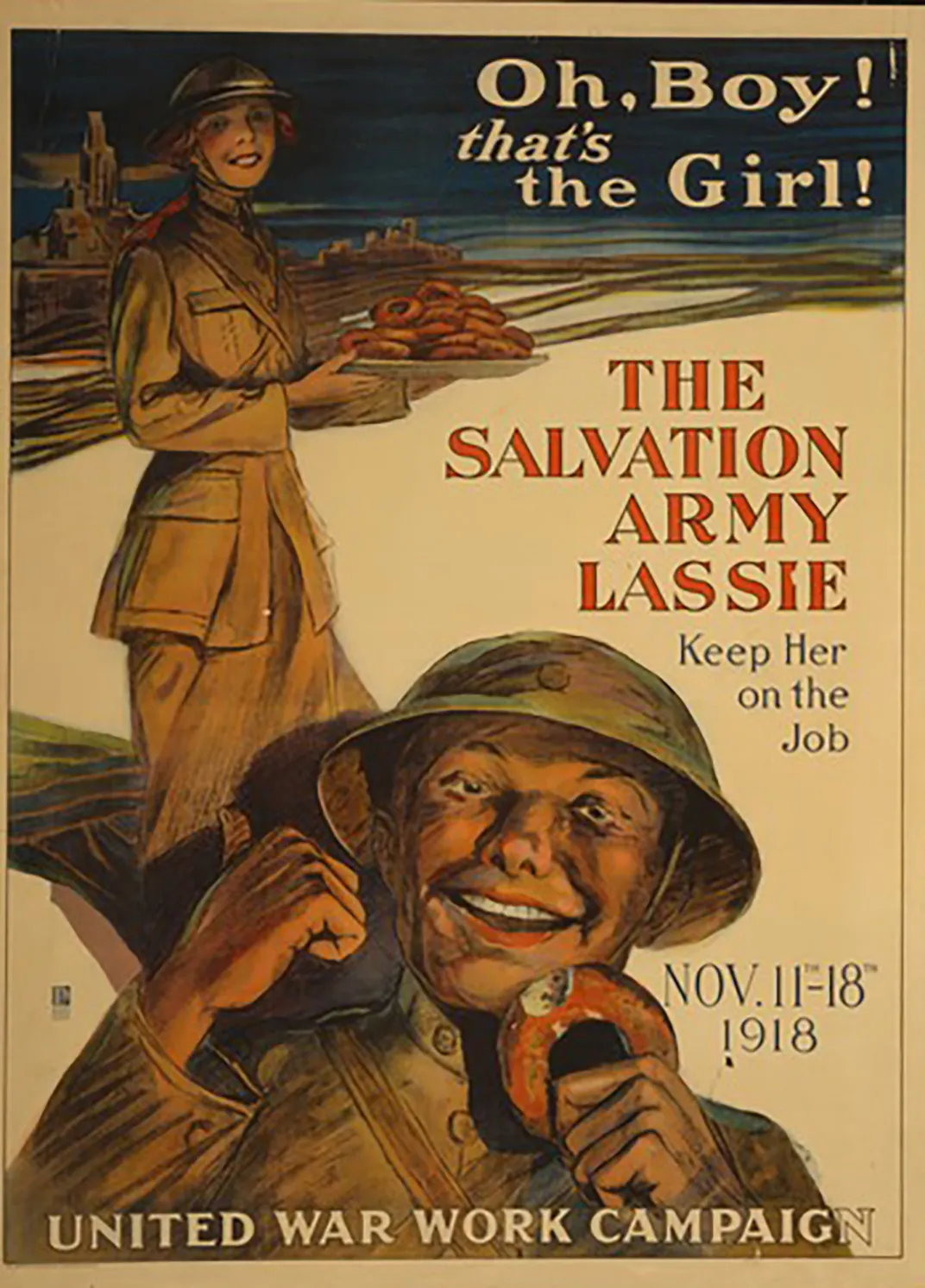

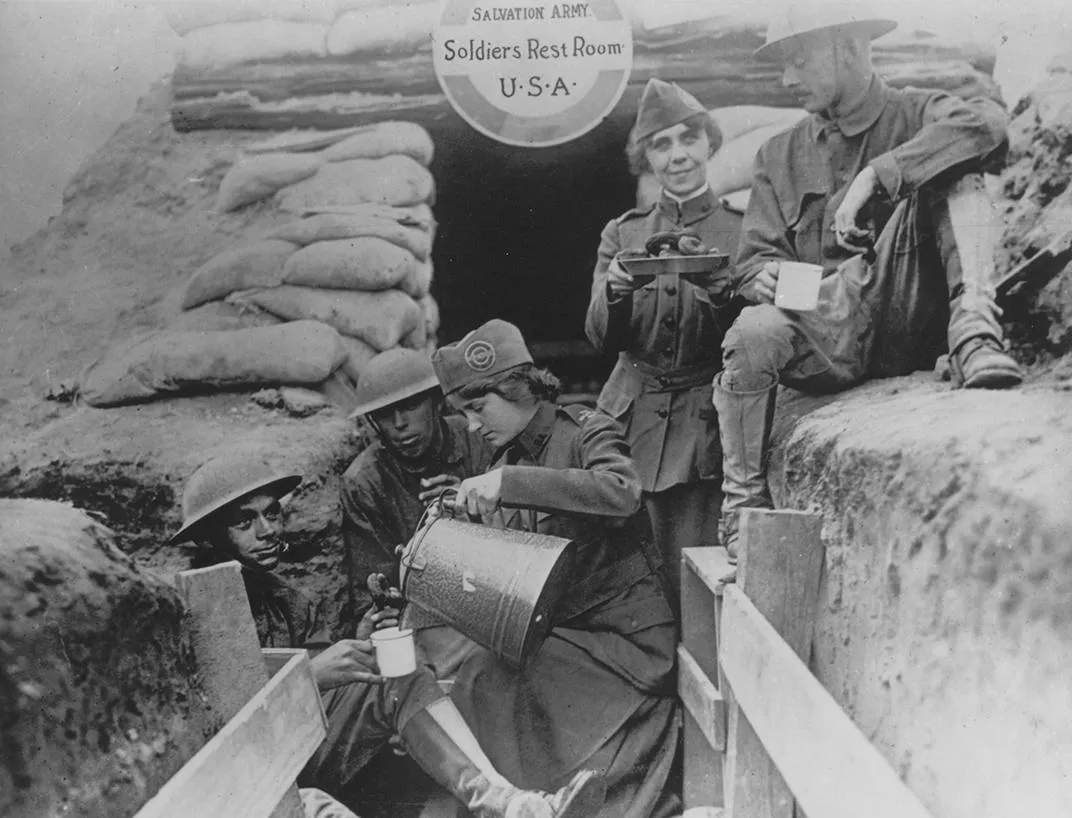

When women of Salvation Army volunteered to join the front lines of World War I to support the American Expeditionary Force, they were given a few obvious supplies: gas masks, helmets and .45-caliber revolvers. But it turned out what they needed most were things much harder for the Army to supply: rolling pins, cookie cutters, flour and sugar.

In September 1917, four women, all members of the evangelical Christian charitable organization, traveled to the camp of the 1st Ammunition Train, 1st Division, mere miles from the trenches of eastern France. Initially they provided the same wholesome activities they’d provided stateside: religious services, music played on a Victrola, and treats like hot cocoa and fudge. Then two of the women hit on a novel idea: what if they made donuts to remind the men of home? And so Margaret Sheldon and Helen Purviance collected excess rations for the dough and shell casings and wine bottles for makeshift rolling pins. They filled a soldier’s helmet with lard to fry the braided crullers. Later they improved their fried creations by combining an empty condensed milk can with a narrow tube of camphor ice to make a cutter in the true donut shape, wrote John T. Edge in Donuts: An American Passion. The treats were an immediate hit, and cemented the Armed Forces’ relationship with donuts, and the girls that served them.

The donuts were simple in flavor, but still delicious, made only with flour, sugar, baking powder, salt, eggs and milk, then dusted with powdered sugar after being fried. One soldier whose letter was reprinted in the Boston Daily Globe wrote, “Can you imagine hot doughnuts, and pie and all that sort of stuff? Served by might good looking girls, too.” And for one WWI reenactor who has experienced the donuts recreated with more modern implements, the treat is delicious—though much smaller than what we’ve come to expect with shops like Krispy Kreme, says Patri O’Gan, a project assistant at the National Museum of American History.

“Well can you think of two women cooking, in one day, 2,500 doughnuts, eight dozen cupcakes, fifty pies, 800 pan cakes and 255 gallons of cocoa, and one other girl serving it. That is a day’s work,” Purviance wrote in a letter home. Despite the Salvation Army sending only 250 volunteers to the front in Europe, the group and their “Donut Lassies” had an outsized impact on the soldiers’ psyche.

“Before the war I felt that the Salvation Army was composed of a well-meaning lot of cranks. Now what help I can give them is theirs,” wrote Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., son of the former president, after serving in France.

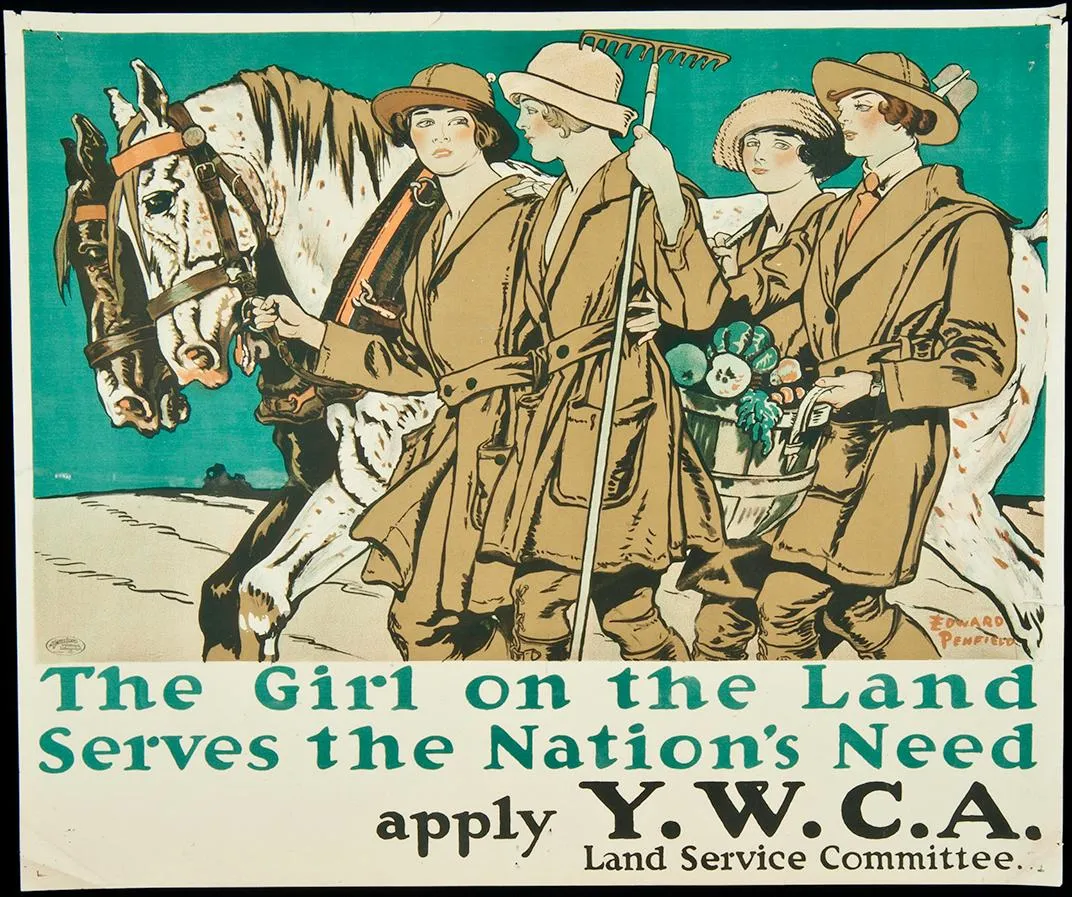

The Salvation Army bakers were just one small part of a larger female war effort. From religious volunteers working through groups like YWCA, the Jewish Welfare Board and Knights of Columbus, to society ladies who formed secular organizations (including Ann Morgan, daughter of J.P. Morgan, who offered the use of her Chateau Blérancourt for the American Fund for French Wounded), women played an important role in the American war effort—and often risked their lives to do so.

“This has continued to come up for 100 years or more. Women have said, we are in combat situations, we just don’t get the credit for being there,” O’Gan says.

One of the Donut Lassies, a 20-year-old woman named Stella Young, recounted her time near the Metz Front when firing was so intense that the Salvation Army supply wagons couldn’t reach them. At one point a piece of shrapnel ripped through their tent and tore through a donut pan just when she’d stepped away from the stove for another ingredient, Young told the Daily Boston Globe years later. Young, who became the face of the Donut Lassies when her picture was taken with a tub full of circular fried dough, recalled the dampness and the cold and the men marching three miles away to the frontline for 30-day stints in the trenches. “So many of them didn’t even belong over there. They were just 16 or 17 years old. They just wanted to serve their country so badly,” Young said.

And for members of religious organizations who may have objected to the war, such service was a way of helping the men caught up in it, O’Gan says. “The Quakers had an organization called the American Friends Service Committee. As conscientious objectors, this was a way for them to do their part for the war effort. You don’t necessarily support the war, but it’s a way to do your part to help your fellow man.”

The work done by all these groups fed into the larger push to get Americans involved in the war. After all, the United States waited until nearly the end to get involved. Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated June 28, 1914 and Germany invaded Belgium August 4, 1914—but the U.S. didn’t make a formal declaration of war against Germany until April 6, 1917. The first national draft registration was on June 5, and the military scrambled to win over (or silence) antiwar protestors. Raymond Fosdick, an attorney and social reformer, was appointed to head the Commission on Training Camp Activities and created a network of social services for the soldiers. Women jumped to play their part, either staying in the U.S. to open hostess houses on the military bases (where men could be visited by family or their sweethearts) or traveled to France as canteen workers.

“There were hundreds of thousands of women serving at home, and quite a bit who went overseas,” O’Gan says. For those who went overseas, uniforms were a particularly useful way of distinguishing themselves from civilians and also projecting an air of professionalism. It was the first time many women were filling roles that would’ve normally been reserved for men, O’Gan says, and the men took notice.

“[The women in combat zones] were providing such a helpful service, a nice break from the atrocities of war that [their presence] was a pretty powerful thing. The work of women in WWI really did lead to suffrage. The number of women in these organizations were doing really needed work and valuable work”—and proving their ability to do so.

Want to try making some Donut Lassies treats? Try the recipe below and then join Smithsonian curators for the program “American History After Hours: Women in World War I” on Thursday April 13, 2017. Attendees will also learn about the role women played in WWI, see the uniforms they wore, and even try some of their famous donuts.

Details about the event and ticket information can be found here.

Ingredients:

5 C flour

2 C sugar

5 tsp. baking powder

1 ‘saltspoon’ salt (1/4 tsp.)

2 eggs

1 3/4 C milk

1 tub lard

Directions:

Combine all ingredients (except for lard) to make dough.

Thoroughly knead dough, roll smooth, and cut into rings that are less than 1/4 inch thick. (When finding items to cut out donut circles, be creative. Salvation Army Donut Girls used whatever they could find, from baking powder cans to coffee percolator tubes.)

Drop the rings into the lard, making sure the fat is hot enough to brown the donuts gradually. Turn the donuts slowly several times.

When browned, remove donuts and allow excess fat to drip off.

Dust with powdered sugar. Let cool and enjoy.

Yield: 4 dozen donuts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)