How 12 Female Cookbook Authors Changed the Way We Eat

A new book examines the recipes of a dozen cooks who made groundbreaking contributions across the food industry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/72/df728cc7-f7b6-4b94-8243-81dc9578b3a9/fannie_farmer_watches_student_cook-main.jpg)

Of all the cookbooks that made their mark in the past 300 years, Fannie Farmer’s The Boston Cooking-School Cookbook—known today as The Fannie Farmer Cookbook—may have changed at-home cooking the most. When Little Brown & Company released the 600-page tome in 1896, the publisher expected minimal sales, and even made Farmer, then principal of the Boston Cooking School, pay for the first 3,000 copies. Yet, she ended up selling 360,000 copies of the book in her lifetime—and more than 7 million to date.

“She invented the style of recipe writing that is consistently followed today: a little header at the top, a short sentence that puts the recipe into perspective, a list of ingredients with quantities in order, and step-by-step instructions,” says Anne Willan, founder of LaVarenne Cooking School in Paris.

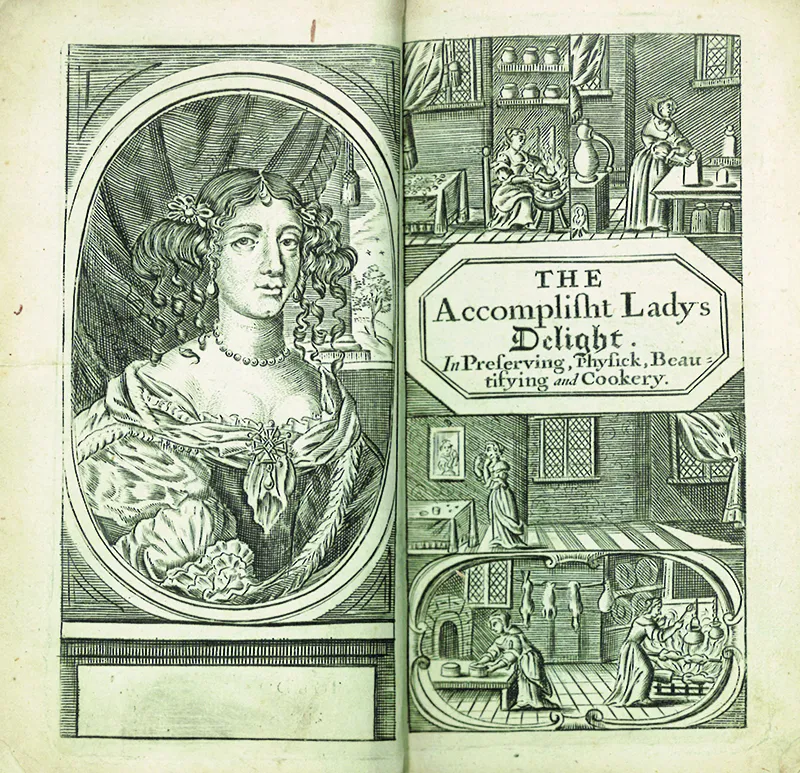

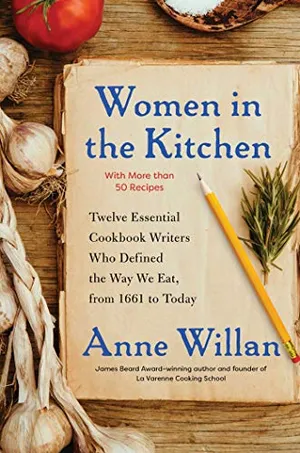

Willan’s new book, Women in the Kitchen, uncovers the ways that 12 female cookbook authors, spanning from 1661 to present day, redefined the way people eat and share recipes. She explores how these women—from both England and America—reshaped the practice of home cooking and broke barriers in the male-dominated food industry. Historically, while women were seen as unequal to their male chef counterparts, female cooks’ style transformed the kitchen; their dishes required less expensive ingredients, simpler tools and included step-by-step instructions. These personable recipes both influenced family tastes and encouraged the passing down of knowledge to aspiring cooks.

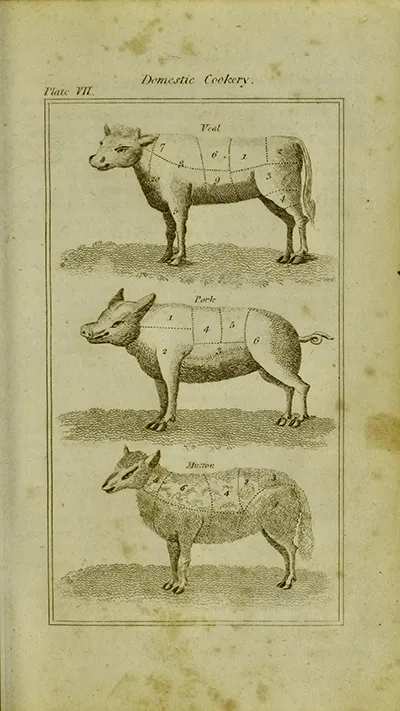

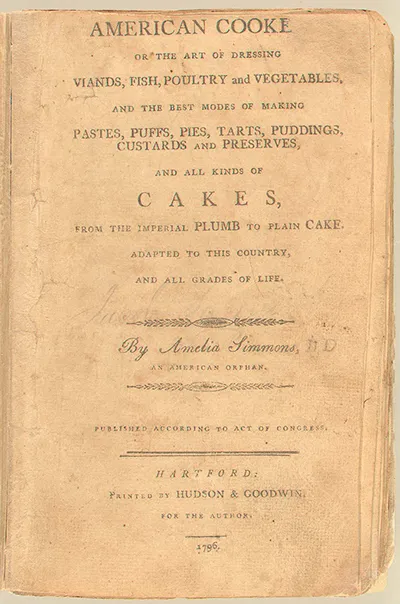

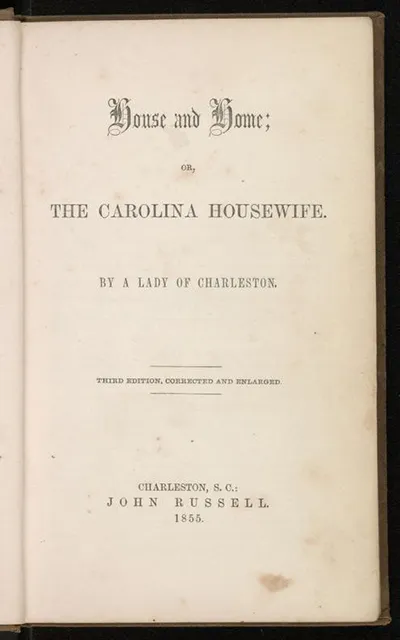

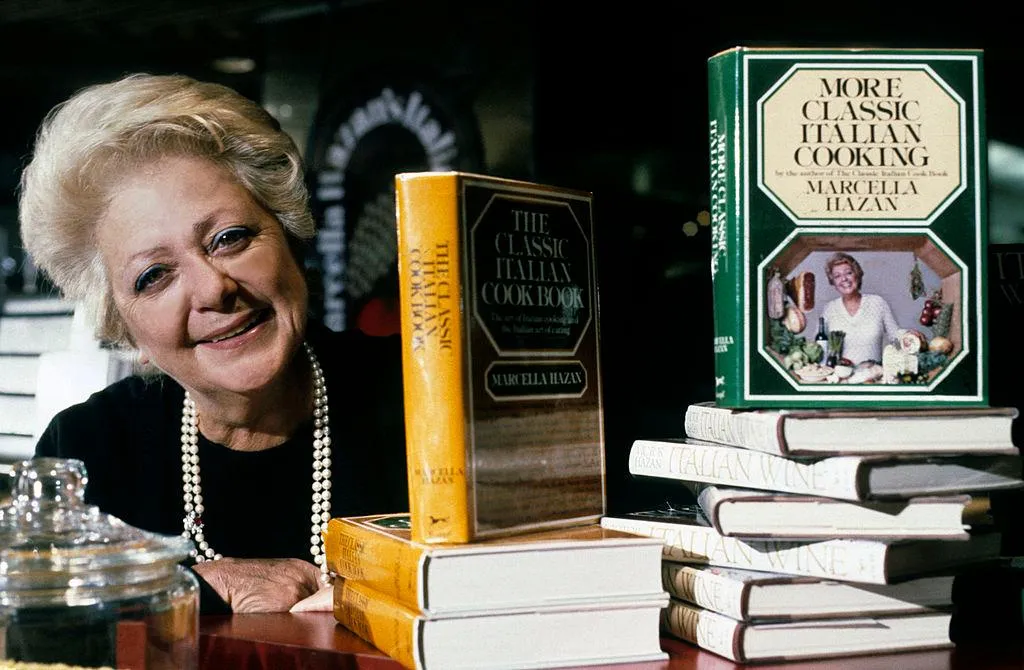

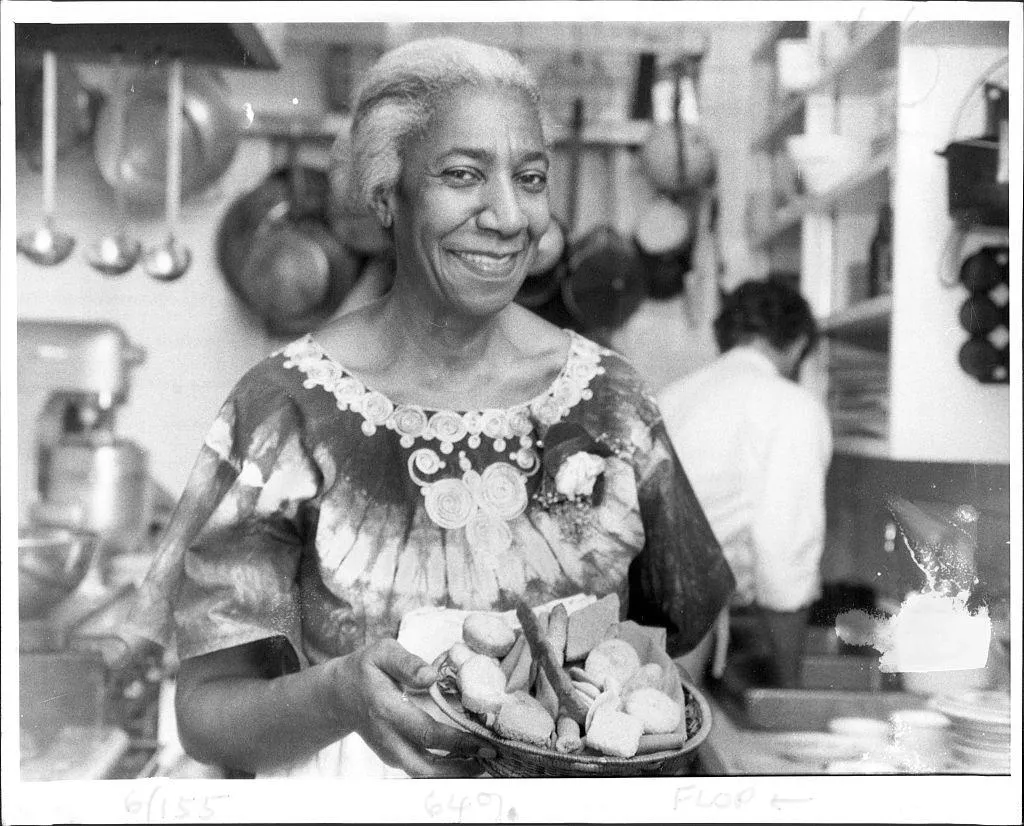

English cook Hannah Glass, for starters, penned The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, considered the most influential cookbook of the 1700s and printed in more than 20 editions. Amelia Simmons’ American Cookery was published across eight different New England towns between 1796 and 1822. Irma Rombauer’s Joy of Cooking, first published in 1931, circulated more than 18 million copies worldwide. Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking, which has sold 1.5 million copies since 1961, even had a resurgence in 2009, appearing on the New York Times bestseller list for nonfiction thanks to the film Julie & Julia. And Edna Lewis’ The Taste of Country Cooking—published in 1976 and chock full of pure and fresh ingredients, southern cultural traditions and childhood stories—was among the first cookbooks written by a black southern woman that did not hide the author’s true name, gender or race. Willan chronicles the lives of each of these cooks (as well as Hannah Woolley, Maria Rundell, Lydia Child, Sarah Rutledge, Marcella Hazan and Alice Waters), incorporating original recipes and offering updated dishes for modern home cooks.

Smithsonian spoke with Willan about the value of a cookbook and how these women found success across their careers.

What made these 12 female cookbook writers stand out for you?

They were all so different, and one fairly clearly led to another in each generation. The very fact that they wrote down and recorded what they are cooking means that they were intelligent women who thought about what they were doing and how they were doing it. This book looks back at the first women who were not just writing down their recipes, but had the initiative to turn their ideas into a reality.

Whoever was in the kitchen had enormous power in the household. For one thing, they were almost certainly buying the ingredients and feeding the family. But that means they were controlling a large percentage of the budget. Throughout history, there was an ongoing saying: “You are what you eat.” Cooking in a household feeds the family and influences them in subtle ways.

Tell me about some of the women in the book.

The women I picked were the ones who led the pack. They wrote the ‘go-to’ books of their generation. Hannah Woolley was writing magazine-style books about beauty and cosmetics for prosperous women. Hannah Glasse was wacky. She was an illegitimate young girl who ran away with a penniless soldier who went bankrupt. Glasse was also a dressmaker to the 18th century Princess Charlotte—which is the front piece of one of her books. She managed to convince a china shop to sell her book, which she wrote when she was in jail for bankruptcy. Her cookbook is special because it has lovely, funny remarks throughout.

Amelia Simmons, an astonishingly buried character, was an early New England semi-pioneer. While her date of birth and death are unknown, she was this sort of modern, liberated woman. Fannie Farmer spent the formative years of her youth as an invalid—she suffered paralysis that left her bed-ridden. But after she attended the Boston Cooking School, she flourished as a writer and was known for her recipes that used precise measurements. People still cook from Fannie Farmer today. And then Alice Waters is [part of] the new generation who most certainly led us into a new era.

You had a close relationship with featured cookbook writer Julia Child—describing her as a “second grandmother to my own children”. Can you tell me about your relationship?

She was a very good friend. She was around when my daughter, Emma, was born and was very fond of her. Our husbands, Paul and Mark, would also sit side by side while Julia and I did our stuff on the stage, also known as our kitchen. They would look at each other and roll their eyes when things went a bit too far.

Why does crafting a cookbook matter in the first place?

There's a nice little rhyme in the introduction of Hannah Woolley’s book:

Ladies, I hope your pleas’d and so shall I,

If what I’ve Writ, you may be gainers by:

If not: it is your fault, it is not mine,

Your benefit in this I do design.

Much labor and much time it hath me cost;

Therefore I beg, let none of it be lost.

‘Let none of it be lost’ is the whole reason for writing a cookbook. These women want their children and their grandchildren to be able to enjoy the tradition. For me, I have two grandchildren who come to my place once a week to make different recipes. Then they take what they make back to their homes so they can get an outsider's opinion. So my book is meant to be taken into the kitchen and enjoyed with younger generations.

Women in the Kitchen: Twelve Essential Cookbook Writers Who Defined the Way We Eat, from 1661 to Today

Culinary historian Anne Willan traces the origins of American cooking through profiles of twelve essential women cookbook writers—from Hannah Woolley in the mid-1600s to Fannie Farmer, Julia Child, and Alice Waters—highlighting their key historical contributions and most representative recipes.

How has the ever-changing kitchen—its expectations and societal norms—influenced the women you write about?

Today, the kitchen is easier and cleaner. You can turn the burner on and off, for example. But my mother, born in 1910, was brought up with the idea that food was never something you paid attention to or discussed at the table. Nowadays of course, it's very different. Julia Child had a lot to do with it because she made the practice of cooking food and enjoying the process so popular. But I think it really began with Irma Rombauer. She must've discussed the dishes she described with her friends. And Fannie Farmer just loved food—she loved going up to New York and eating in the newest restaurants.

How do these women pave the way for future budding female cookbook writers?

It’s now taken for granted that any female chef must have a cookbook—whether or not they've written it themselves. Now there’s a whole subset profession of writing cookbooks for other people. These women inspired future budding cooks to write down what they were doing, whether by hand or on a blog online.

Why do you find cooking and cookbooks so important?

Well, the one thing about cooking is that it’s about the people you're cooking for. It involves sitting down at the table with family and friends and talking about the food you’ve created. Cooking pulls in all sorts of people and new experiences, such as the butcher and the way you buy your ingredients. It involves a much wider world than just the kitchen.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)