How Archaeologists Are Unearthing the Secrets of the Bahamas’ First Inhabitants

Spanish colonizers enslaved the Lucayans, putting an end to their lineage by 1530

:focal(952x607:953x608)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/15/7c1533fb-a9d5-49a3-ba28-0be1987168d9/7.jpg)

When the Reverend Theophilus Pugh heard about a mysterious wooden stool discovered in a cave in the Bahamas around 1820, he bought it on the spot “for a trifle.” Uncertain of the object’s history, he nevertheless recognized it as a significant find, describing the centuries-old seat as “either a piece of domestic furniture of the Indians or one of their gods.”

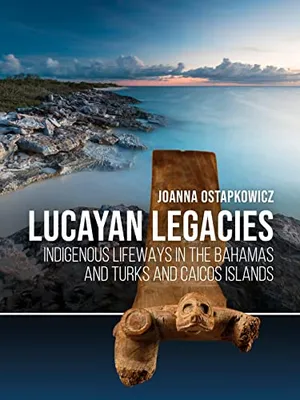

Over the next 150 years or so, collectors like Pugh stripped the region of its ancient past. “A large slice of the islands’ archaeological heritage was lost to building work, tourism and the mining of cave earth—valuable bat guano known as ‘black gold’—to fertilize fields,” says Joanna Ostapkowicz, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford and the author of Lucayan Legacies: Indigenous Lifeways in the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands.

In the late 19th century, a tramway on East Caicos fast-tracked guano to a coastal wharf for export. Later, developers used dynamite to clear land for banana trees, destroying even more traces of the original inhabitants of the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos. Archaeologists eventually transferred many of the artifacts linked to these Indigenous peoples, now known as the Lucayans, to cultural institutions like the American Museum of Natural History, the British Museum and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Lucayan Legacies: Indigenous Lifeways in the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands

This comprehensive study aims to foreground the material culture of the Lucayans, making it more accessible and reinstating it as an important part of the region’s archaeological heritage.

Also called the Lukku-Cairi—a name that translates to “people of the islands”—the Lucayans were part of the broader Caribbean-based Taíno civilization. They settled in the area no later than 700 C.E. and adopted a largely maritime lifestyle. The Lucayans were the first Indigenous group encountered by Christopher Columbus when he arrived in the New World, as well as the first to disappear from the continent in the early 16th century.

Contemporary chroniclers described the Lucayans in racist, colonialist terms, scorning them as people of “primitive simplicity [who] went about as naked as their mothers bore them.” Columbus, who anchored off the island of Guanahani on October 12, 1492, wrote of their “unpleasantly broad foreheads” (the result of deliberate cranial modification) and olive-colored skin, which he suggested gave them the appearance of “sunburnt peasants.” He also noted that the Lucayans painted their bodies with red, black and white pigments.

Gold doesn’t occur naturally in the Bahamas, so Spain categorized the archipelago as islas inútiles, or “useless islands.” Today, archaeological analysis is redefining this characterization, revealing the rich culture of the now-vanished Lucayan people.

How the Lucayans lived

In Freeport, a city on Grand Bahama Island, white sands backed by turquoise waters stretch as far as the eye can see. Local restaurants serve up specialty fritters made from conch, a giant sea snail that’s local to the Bahamas. Humans have enjoyed this idyllic paradise for 1,300 years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/65/26/6526ace7-13dd-4cf8-81a9-ad111d3afb19/011700x700.jpg)

Ostapkowicz speculates that lush woodlands, rich soils, abundant marine resources and steady rainfall ideal for horticulture encouraged people to migrate from Hispaniola and Cuba to the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos in waves, starting around 700.

The Lucayans lived in villages made up of 12 to 15 houses called bohios. Families of up to 15 people slept on cotton hammocks in these round structures; fire pits kept pesky mosquitoes at bay.

Tending gardens filled with manioc, maize, sweet potato and chili peppers was a daily ritual for these Indigenous people. The Lucayans hunted large rodents known as hutias and trapped exotic birds. (Parrot feathers were highly valued as accessories in hair ornaments and headdresses.) Dogs walked alongside their owners at home and in huge forests of pine, cedar and ironwood, the “loveliest groups of trees that I have ever seen,” according to Columbus.

The Lucayans loved their dogs, which looked like large mastiffs or small terriers, research led by the late Jeffrey P. Blick shows. They even wore dog molars as pendants, suggesting the animals’ symbolic significance in Lucayan culture. One possible explanation for this tenderness is the belief that dogs were divine: After all, the four-legged spirit Opiyelguobirán was said to guard the dead in the afterlife.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e6/b8/e6b8589c-3900-4da4-a72f-5e77cb02088a/2.jpg)

If the Lucayans lived, slept and dreamed on land, then the ocean was their larder and inspiration. “You find bones from marine animals everywhere on land digs,” says Michael Pateman, a Lucayans expert and the director of the Bahamas Maritime Museum. “Archaeology shows that over 80 percent of the Lucayans’ meat came from marine fish. And the menu was long. On Grand Turk island, 32 species of fish were dug up in Coralie alone.”

Grunts, parrotfish, groupers, snappers and jacks were particularly popular seafood species. From the shallows, the Lucayans harvested fish by hand. Elsewhere, they used basket traps and weirs to catch sea urchins, spiny lobsters and blue crabs. In deeper waters, they fished with hooks, lines and spears topped with stingray spines. To catch turtles—prized for their meat and shells, which could be turned into cooking vessels and adornments—the Lucayans used spears that looked like wooden lances and nets.

“Working day in, day out in the sea, especially harvesting conch shells, made the Lucayans the Caribbean’s greatest free divers,” says Pateman. Protein-rich conch could be eaten raw, steamed, boiled or roasted. Dried and preserved, the snail’s meat stayed fresh for up to six months. The Lucayans recycled conch shells as trumpets, tools and insulation for cooking hearths. “Broken shells littering archaeological sites in the Bahamas are a virtual calling card of the Lucayan past,” Pateman adds.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7b/65/7b65df4b-487e-4ad2-b0a9-223d7bd3342f/6.jpeg)

Canoes were key to the Lucayans’ maritime success. The transportation method even impressed Columbus, who deemed the vessels “very wonderfully carved” in one piece. Propelled with paddles, the canoes were large enough to hold around 45 men and could travel at fast speeds.

The Lucayans also used canoes for trade, exchanging such goods as raw cotton, hammocks, shell beads, parrots, conch and salt. On their return journeys, Lucayan crews brought home gold, ceramics and stone artifacts from Hispaniola, Cuba and other trading partners.

Excavating the Lucayans’ history

In 2007, Pateman participated in an excavation at Preacher’s Cave on the Bahamian island of Eleuthera, where a group of Puritan English settlers expelled from Bermuda due to their religious beliefs found themselves shipwrecked in 1648. The dig team discovered the ends of tobacco pipes smoked by the Eleutheran Adventurers. But the would-be migrants’ garbage masked a far older prehistory: the remains of several Lucayans, including a 25- to 30-year-old man who was laid to rest with an Atlantic triton shell (probably used as a drinking cup) on his chest. Behind his left shoulder was a charm made up of 29 iridescent sunrise tellin shells, a lump of red ocher and a fish bone tool used to scratch designs into human skin. The bones of a sea turtle lay at his feet.

“These unusual grave goods were all instruments of power and faith,” Pateman says. “Our best thinking is that this was a shaman or cacique, a local ruler, buried with his wife and matriarch of the community, maybe as early as 1050.”

Spanish clergyman Bartolomé de las Casas believed the Lucayans were simple people who had a “confused knowledge” of God. But data from around 120 burials spanning the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos suggests the group engaged in religious rituals, some of which centered on water. In a world where dying young was the norm, says Pateman, “the Lucayans felt very vulnerable, so guidance from the ancestors and spirits was an essential reassurance.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/93/9b/939b435b-7c9d-46d5-8586-b577396358c3/duho.jpg)

Lucayan leaders “met” their ancestors with a little hallucinogenic help. In caves adorned with rock art, archaeologists have found pestles, a vomiting spatula and a hollow bird bone snuff tube—paraphernalia associated with attempts to commune with the spirit world.

According to Ostapkowicz, all of the surviving duhos, or ceremonial stools like the one acquired by Pugh in the mid-19th century, come from caves in the Bahamas. The low-standing seats depict part-human, part-animal figures on all fours. Many were carved from lignum vitae, one of the world’s hardest woods. The tree’s sacred reputation even inspired the Spanish to grind its wood into a treatment for syphilis. Slumped on these seats, Lucayan caciques, or “big men,” went into drug-induced trances. The furrowed brows of the creatures on the stools, with their sunken eyes, plump cheeks, and mouths once inlaid with gold and shells, are the faces of the ancestors staring back through time.

Preserving Lucayan heritage

Beginning in 1998, the Antiquities, Monuments and Museum Act made it illegal to excavate or remove artifacts from the Bahamas without a permit. But the law arrived too late to save much of the Lucayans’ heritage. “An unimaginable amount of finds are long gone,” says Ostapkowicz. “Many artifacts documented in the 19th century have simply disappeared; others, like the wooden canoes found in caves, have been destroyed. Of the 26 duhos discovered, 15 survive—with only 4 remaining in the Lucayan Archipelago itself.”

Is this the end of the line for exploring the Lucayans’ history in the Bahamas? Pateman thinks not. Rising sea levels destroyed many eighth- and ninth-century sites, but others remain. “There are more than 850 caves in the Lucayan Archipelago, running miles underground. And in some of them lie precious archaeology,” Pateman says. “Take Stargate Blue Hole Cave on Andros Island, where a wooden canoe burial offering has turned up. Who knows how many similar time capsules are in these underwater caves?”

What survives below is important because archaeology is the only witness left to make sense of a lost civilization. In 1509, Spanish slave raiders started kidnapping the people of the “useless islands” of the Lucayan Archipelago and putting them to work in Hispaniola’s gold mines. Later, the Spanish exploited the Lucayans’ skill at diving for conch shells by sending them to the lucrative pearl fisheries off the coast of Venezuela.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/63/61/6361b425-89ce-4a7a-99a0-11e0cc4e2198/14.jpg)

The situation was so dire that las Casas, appointed the “protector of the Indians” by the church, observed that the Spanish could sail to Hispaniola simply by “following the trail of bodies in the water.” He added, “There was never a ship went slaving in the Lucayans … that did not throw into the sea a quarter or a third of those it caught and embarked.”

In total, the Spanish enslaved an estimated 40,000 Lucayans, driving the islanders to near- extinction by 1530. “There is certainly no more eloquent statement of the thoroughness of Spanish slave trade in the Bahamas than the mute testimony of 600 uninhabited islands at the arrival of the first British settlers in the late 1500s,” wrote anthropologist Julian Granberry in 1981.

“The early Spanish writers spoke about the Lucayans as simple innocents,” says L. Antonio Curet, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. “The lack of signs of warfare, also in the archaeological remains, was seen as a lack of sophistication. This was an unfair take that dehumanized the reality of a mosaic culture of well-connected peoples with a rich kinship.”

DNA studies confirm the genetic diversity of the modern Bahamas’ inhabitants. But no descendants of Lucayan heritage are known to survive today. As Pateman says, “If we don’t make use of DNA, phenotypic morphometrics, stable carbon and nitrogen isotope to reconstruct diet, strontium isotope to assess origins, and accelerator mass spectrometry to figure out how humans migrated across the Bahama archipelago, then the Lucayans’ hard drive will be wiped clean forever.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.