Sugar Masters in a New World

Sevilla la Nueva, the first European settlement in Jamaica, is home to the bittersweet story of the beginning of the Caribbean sugar trade

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/sugar-factory-West-Indies-631.jpg)

Until the discovery of the New World in the late 15th century, Europeans hungered for sugar. So precious was the commodity that a medieval burgher could only afford to consume one teaspoon of the sweet granules per year. And even in Europe’s early Renaissance courts, the wealthy and powerful regarded the refined sweetener as a delicious extravagance. When Queen Isabella of Castile sought a Christmas present for her daughters, she chose a small box brimming with sugar.

The commodity’s preciousness came, of course, from its relative scarcity during this period. Sugar cane—the sole source of the sweetener—only really flourished in hot, humid regions where temperatures remained above 80 degrees Fahrenheit and where rain fell steadily or farmers had ample irrigation. This ruled out most of Europe. Moreover, sugar-mill owners required huge quantities of wood to fuel the boiling vats for transforming cane into sugar cones. By the early 16th century, sugar masters along the southern Mediterranean, from Italy to Spain, struggled to find enough cheap timber.

So European merchants and bankers were delighted by reports they received from Spanish mariners exploring the Caribbean. Jamaica possessed superb growing conditions for sugar cane, and by 1513, Spanish farmers in the island’s earliest European settlement, Sevilla la Nueva, tended fields bristling with the green stalks. But until very recently, historians and archaeologists largely overlooked the story of these early would-be sugar barons. Now a Canadian and Jamaican research team led by Robyn Woodward, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, has studied Sevilla la Nueva’s fledgling sugar industry and excavated its mill. “It’s the earliest known sugar mill in the New World,” says Woodward.

Woodward first walked the site in 1981 while searching for traces of Christopher Columbus and his fourth expedition: the mariner had spent nearly a year in the immediate region after beaching two of his ships in St. Ann’s Bay on Jamaica’s north coast. Columbus possessed a detailed knowledge of the eastern Atlantic’s Madeira Island sugar industry—he had married the daughter of a wealthy Madeira sugar grower—and he clearly recognized Jamaica’s rich potential for growing the crop. Moreover, at least 60,000 indigenous Taino farmers and fishers lived on the island, a potential pool of forced laborers. But Columbus died before he could exploit this knowledge. Instead, it was his son Diego who dispatched some 80 Spanish colonists to the north coast of Jamaica in 1509. There the colonists subjugated the Taino, planted sugar cane and corn, and founded Sevilla la Nueva, the island’s first European settlement that, in spite of its relatively brief history, tells a crucial story about the colonization of the Caribbean.

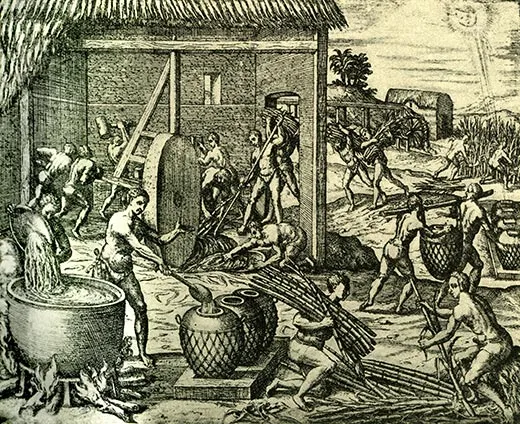

According to surviving records, the inhabitants of Seville la Nueva did not begin milling sugar until the arrival of their second governor, Francesco de Garay, in 1515. Garay, a former slave trader in the Bahamas, had made his fortune in Caribbean gold fields. He devoted part of this wealth to constructing a mill in Sevilla la Nueva capable of churning out 150 tons of sugar a year for European markets. He was in the process of building a second mill at the time of his departure for Mexico in 1523.

Troweling into the sediments, Woodward’s team uncovered the ruins of Garay’s large, water-powered sugar mill, complete with a brick-lined tank for holding cane-sugar juice and an ax and a stone block that workers had used for chopping cane. Almost certainly, says Woodward, Garay chose to house all the heavy equipment in simple, open-sided thatched sheds, as opposed to more permanent brick or stone buildings. “This is all very expedient,” she says. If Garay had been unable to make a go of it at the site, he could have moved the expensive equipment elsewhere.

Documents strongly suggest that Garay brought 11 enslaved Africans to Seville la Nueva, but excavators found no trace of their existence in the industrial quarter. Instead, Garay relied heavily on coerced Taino laborers. Woodward and her colleagues recovered pieces of Taino stone blades littering the ground near the mill, suggesting that the Taino were cutting and processing the tough cane stalks and doing heavy manual labor. In addition, the Spanish colonists compelled Taino women to prepare traditional indigenous foods, such as cassava bread, on stone griddles.

But while Garay and the colonists worked closely with Taino villagers and dined on native fare, they determinedly kept up Spanish appearances in public. They made a point, for example, of dining from fine imported Majolica bowls—rather than local Taino pottery—in the industrial quarter. “These were Spanish people wanting to show off their Spanishness,” explains Woodward.

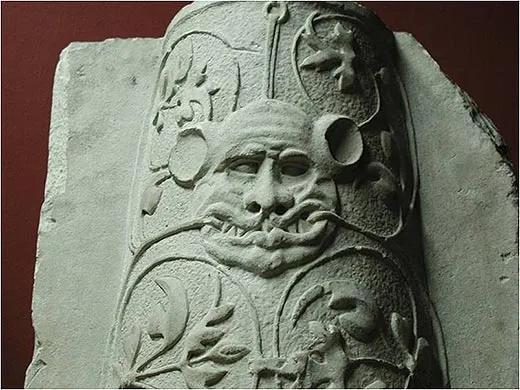

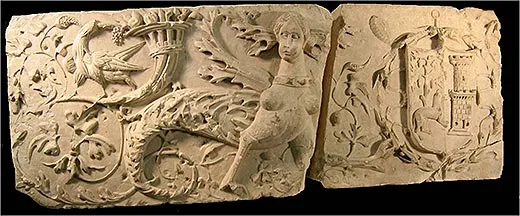

The excavations also reveal much about the grand ambitions of the early Spanish entrepreneurs. In Sevilla la Nueva’s industrial quarter, the archaeologists unearthed a massive sculptor’s workshop littered with nearly 1,000 carved limestone blocks of archangels, griffons and demons—the largest collection of Renaissance sculpture ever discovered in the Americas. These were destined for the altar of a magnificent stone abbey the settlers planned to build. Sevilla la Nueva, says David Burley, a historical archaeologist at Simon Fraser University, “is one of the best preserved early Spanish colonial settlements by a long measure.”

But the town never lived up to its founders’ great expectations. Its colonists failed to reap sufficiently large profits, and most abandoned the site in 1534, settling instead on the island’s south coast. Moreover, the sugar industry they founded in Jamaica took a tragic toll on human life. European germs and exploitation virtually extinguished Jamaica’s Taino in just one century. Without this large coerced workforce, Jamaica’s sugar economy faltered until the British seized the island in 1655 and set up a full-scale plantation system, importing tens of thousands of enslaved Africans. By the end of the 18th century, African-American slaves outnumbered Europeans in Jamaica by a ratio of ten to one.

Despite its short history, says Woodward, the Spanish colony at Sevilla la Nueva tells us much about the birth of the sugar industry in the New World, a global trade that ultimately had an immense long-term impact on the Americas. The growing and milling of sugar cane, she points out, “was the primary reason for bringing ten million Africans to the New World.”