This Tiny French Archipelago Became America’s Alcohol Warehouse During Prohibition

Before the 21st amendment was ratified, remote islands off Canada’s Newfoundland province floated on a sea of whiskey and wine

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/89/00891603-7017-4bd3-b1e8-bdbe43f9367b/img_20180104_0001.jpg)

The tiny islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon—cold, fogbound and windswept specks in the North Atlantic midway between New York City and Greenland—lie far closer to polar bears and icebergs than the speakeasies and clubs where Americans tippled during Prohibition. But thanks to quirks of geography, history and law, the French archipelago served up much of the booze that Prohibition was supposed to keep Americans from drinking.

The remote islands imported a total of 98,500 liters in all between 1911 and 1918. That was before Prohibition began on January 16, 1920. A decade later, with the ban on the production, importation and sale of alcohol in full swing, more than 4 million liters in whiskey alone flowed into the islands’ warehouses—along with hundreds of thousands of cases of wine, Champagne, brandy, and rum—and then flowed right back out. Almost every drop went aboard rumrunners—smugglers’ ships sailing south with their costly cargo to quench an insatiable American thirst for the prohibited booze.

During Prohibition, the port in St. Pierre, about a thousand nautical miles north of New York City, became a wholesale trading post for the alcohol Americans craved. Although 2,400 miles from the homeland, the French colonial possessions sit just 16 miles off Canada’s Newfoundland province; nonetheless, they remain the last vestiges of French territory from the wars that long ago divvied up North America. For centuries, the hearty islanders—about 4,000 inhabitants in 1920 and a little over 6,000 today— made their living off the sea, mainly by fishing for cod. Prohibition changed everything. Fishermen pulled their dories up on land and hung up their nets and lines while their home islands floated on a veritable sea of whiskey, wine and money.

Despite the ban on booze, millions of Americans still wanted to drink. Canadians were willing to supply their needs, and when the Canadian government tried to halt the bootlegging trade with its southern neighbor, the French citizens of St. Pierre and Miquelon sailed to the rescue.

Canadians actually faced a mixed bag of alcohol restrictions themselves; no laws prevented them from making liquor, just selling it, and when U.S. production ended, the volume of whiskey Canada’s distilling industry produced exploded. All of those millions of gallons of high proof alcoholic drinks should have remained in their distilleries, because, by law, nobody could purchase it almost anywhere in North America. Yet eager hands were willing to fork over lots of dollars to purchase the Canadian products and smuggle bottles and barrels of whiskey, vodka, bourbon and rye south over the border. The problem was how to get the valuable contraband across the line and into American drinkers’ hands. At first, the 3,987-mile boundary between the two countries proved little more than a line on a map. Smugglers departed Canada for the U.S. in cars and trucks with secret compartments filled with booze. Far more motored in fast boats plying the Detroit River from Windsor, Ontario, a major distilling center, through what became known as the “Detroit-Windsor Funnel.”

Big money was made bootlegging; north of the border fortunes were also being made. While entirely dependent on American gangsters like the notorious Al Capone for their delivery, distribution and sales networks, Canadian distillers flourished like never before. Many of today’s well-known brands became part of the American speakeasy scene during Prohibition, including The Hiram Walker Company’s immensely popular Canadian Club and Samuel Bronfman’s Distillers Corporation’s North American distribution of Scotland’s Haig, Black & White, Dewar’s, and Vat 69 whiskey brands and, after a 1928 merger, production of Seagram’s ‘83 and V.O.

Nobody knows just how much booze flowed across the border, but many profited. Revenues from liquor taxes to the Canadian government increased fourfold during Prohibition despite statistics that suggest Canadians’ own drinking fell by half.

However, overland transport grew more and more risky as a result of crackdowns by federal agents and battles among gangsters for a piece of the lucrative trade. Bootleggers looked to the immense Eastern seaboard coastline, with its many ports, small inlets and hidden docks. A single “bottle-fishing” schooner could carry as many as 5,000 cases of liquor bottles.

Those ships sailed to just beyond the U.S. three-mile territorial limit, the “rum line.” Once there, by international law, they were outside the reach of the Coast Guard. They anchored at predesignated spots, “rum row.” Business was open at what Daniel Okrent, author of the lively and comprehensive Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, describes as long rows of “wholesale liquor warehouses” anchored offshore. “Someone said,” Okrent told me, “that when viewed from the Truro Lighthouse on Cape Cod, rum row looked like a city out there because there were so many lights from the boats.” Rum rows flourished off virtually every coastal metropolitan center from Florida to Maine.

However, almost all of this illegal commerce came crashing down in 1924. That’s when St. Pierre and Miquelon took center stage in the Prohibition story.

Even in the first years of Prohibition, St. Pierre and Miquelon had taken advantage of its “wet” status as a French territory. At first, several bars opened in St. Pierre’s harbor port to serve sailors who came from St. John’s, Newfoundland, and Halifax, Nova Scotia, as well as off fishing schooners in from the Grand Banks. They got drunk and staggered away with a few bottles to bring back to their ships.

But rumrunners saw far more potential in the “foreign” port. The islands, so close to Canada and a few days’ sail to New England, offered a new way to bring booze to their U.S. customers. According to Okrent, bootlegger Bill “the Real” McCoy, already running rum and gin and French wines from the Caribbean, was among the first to realize the advantages of St. Pierre. He arrived in port with a schooner, took on a load of imported Canadian whiskey, and started regular runs to New England.

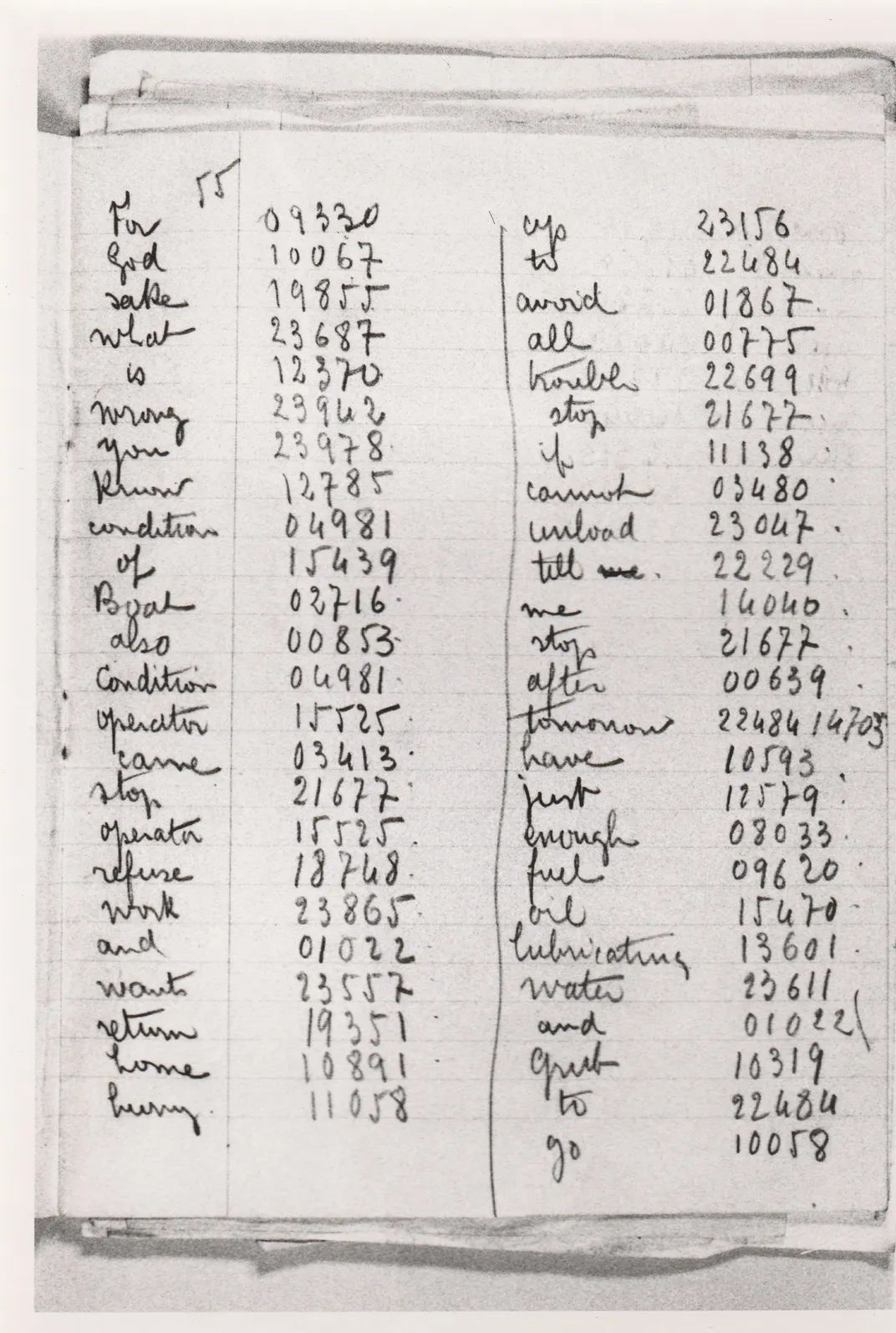

Jean Pierre Andrieux now lives in St. John’s, Newfoundland, but lived much of his life in St. Pierre where, among other businesses, he operated a hotel for many years. He has written numerous histories of the islands, including Rumrunners: The Smugglers from St. Pierre and Miquelon and the Burin Peninsula from Prohibition to Present Day, an illustrated history drawing on his personal archives of thousands of photographs and other documents from the Prohibition era. Andrieux says that an old rumrunner gave him much of the material and told him how the business worked. “He kept all his records and letters from people buying products from him. He even had the code books he used to send secret messages to buyers to avoid Coast Guard patrols and pirates,” says Andrieux.

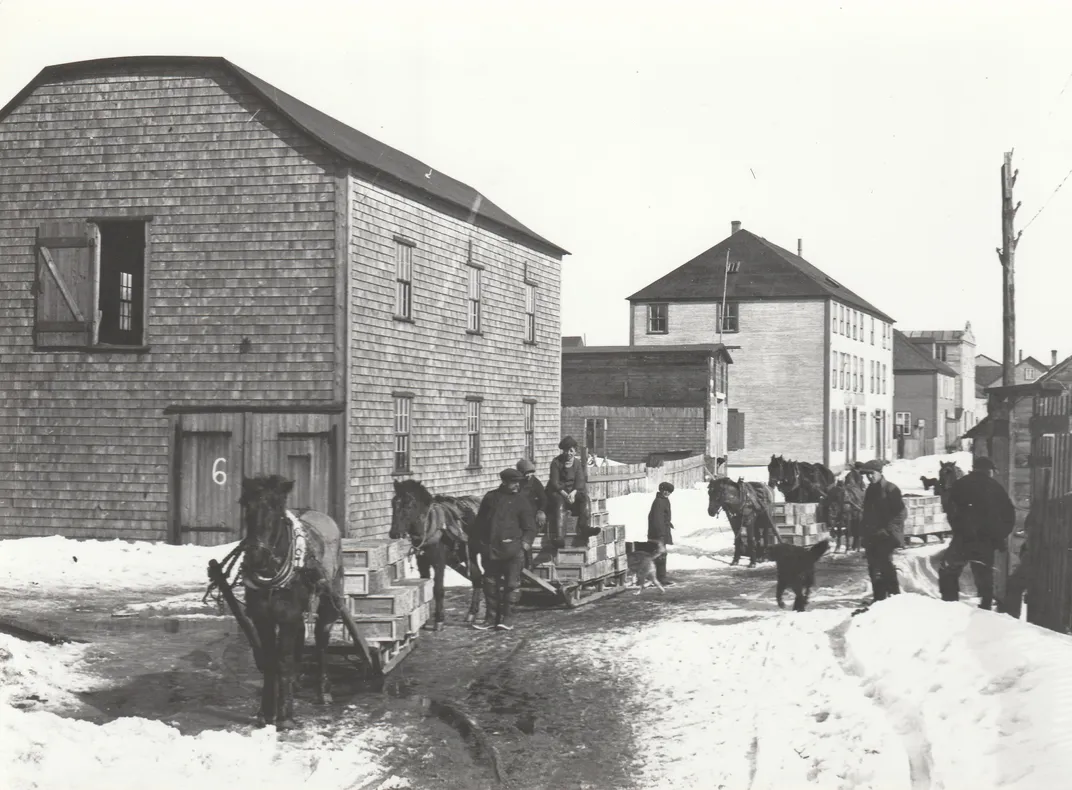

The tiny island of St. Pierre, the commercial center of the archipelago, though just a tenth the size of Nantucket, is blessed with a large and deep harbor. Booze, money and bootleggers surged in like a vast rising tide. Large concrete warehouses went up along the waterfront. “Seven or eight are still standing,” Andrieux says. The biggest warehouses belonged to Bronfman’s Seagram’s Northern Export Co., which, according to a French government report, by 1930 accounted for around 40 percent of the whiskey trafficking that came into the St. Pierre, four times more than any other competitor. Those warehouses brimmed with stockpiles of wine, Champagne, and spirits, above all Canadian whiskey and rye, legally shipped directly to “France.”

The islanders could credit their liquor-trading success to Canada’s desire to curtail illegal exports. In 1924 Britain and Canada made a concerted attempt to honor American Prohibition law, the two nations agreeing to ban export of alcohol to the U.S. Canada would, supposedly, no longer turn a blind eye to where those millions of gallons of whiskey pouring out of its distilleries were going. However, France refused to sign on to what was known as the Liquor Treaty.

Andrieux explains, “By law, Canada now required that all vessels carrying alcohol be ocean-worthy and receive a stamp from the receiving port certifying the cargo’s arrival.” That was intended to prevent Canadian booze getting smuggled into the U.S. market next door. But French St. Pierre and Miquelon offered an easy and entirely “legal” way around the ban on export to the southern neighbor. The French islanders were happy to have their big harbor transformed into a way station for southbound booze.

They gave up cod fishing to earn better wages as stevedores, drivers and warehouse workers. The quiet harbor was suddenly ablaze with light, noise, ships and workers at all hours of the day and night. Ships arrived and the island workers sprang into action, unloading the crates and barrels of booze from as far away as Europe and Vancouver, but mostly from distilleries in Windsor and Montreal. Once offloaded, the cases of whiskey and wine were brought from the docks to the warehouses, where they were quickly opened. According to Andrieux, workers carefully slipped individual bottles into burlap sacks, then packed them with straw and finally gathered the outbound orders into larger sacks for export, muffling the telltale clank of rattling bottles against any prying eyes on the tossing sea.

The discarded wooden crates got broken up for firewood or used as building materials, he says. One house on St. Pierre is still known as the “Villa Cutty Sark” thanks to the recycled whiskey crates that went into its construction.

Orders came by mail, telegraph and telephone. American gangsters came to the warehouses, too, to inspect the goods and place their orders for shipments to the U.S. Andrieux’s family lore has it that Capone himself visited St. Pierre, but Okrent insists, “There’s no evidence to support that Al Capone ever went anywhere near Saint Pierre.”

At first old freight schooners were used to transport the repackaged bottles down to the Atlantic seaboard’s rum rows. According to Andrieux, determined bootleggers wanted bigger and faster ships for their valuable stock. After a surplus sub chaser left from World War One proved its worth as a rumrunner, shipbrokers commissioned Nova Scotia shipyards to build dedicated versions for rumrunning. Loaded up, with customs papers showing a cargo bound for the high seas or supposed Caribbean destinations, Andrieux says that some 80 such vessels—often with faked registry papers—made regular runs from St. Pierre to East Coast rum rows and back for more cargo. “When the world went into the Great Depression” in 1929, says Andrieux, “Saint Pierre was booming.”

In 1930, the French Foreign Ministry sent a special inspector to St. Pierre and Miquelon to study the effect of the massive bootlegging trade on the islands. He met with local officials, observed conditions, and reported on legal and international issues, tax revenues and the economic and social impact of smuggling alcohol on the islands. He wrote that in all the time between 1911 and 1918, just 11,000 cases of alcohol in total were imported into St. Pierre and Miquelon. In the second year of Prohibition, 1922, the islands imported 123,600 cases of whiskey; the following year that more than tripled, to 435,700 cases, more than a 40-fold increase over the entire previous decade.

According to his report, though, the demand for whiskey seemed virtually insatiable. In 1929, 5,804,872 liters of whiskey—that’s 1,533,485 gallons of the hard stuff (equivalent to two overflowing Olympic-size swimming pools)—poured into the islands, worth some $60 million, equal to almost $850 million today. He projected that close to 2 million gallons of high-proof whiskey would flow through St. Pierre in 1930. That’s enough to fill better than 220 large tank trucks.

That business proved a phenomenal boon to the island economy. The islanders had previously lived from what the French inspector called the “hard craft” of bringing cod in from the ocean while depending on the distant French government’s assistance to stay afloat. Thanks to soaring taxes, customs revenues and export fees—“unhoped for riches,” he wrote—the island government now ran a huge surplus, allowing it to build new roads, schools and other public facilities. Seeing the islanders’ newfound prosperity, he considered the alcohol trade “only a crime in the Americans’ eyes.”

He concluded his 1930 report with an ominous warning to the French government that passing laws to halt or otherwise control the smuggling of alcohol would prove “catastrophic” for the islands. He feared that without rumrunning the islands would spiral into decline.

He was right. Three years later catastrophe struck. The American government finally acknowledged the obvious. Thanks in part to St. Pierre’s intrepid, relentless and entirely legal import-export trade in booze, Prohibition had failed. On December 5, 1933, it officially ended.

For St. Pierre and Miquelon, the high life had ended, too. Andrieux told me that Hiram Walker, Seagram and other distillers sent thousands of empty barrels to St. Pierre. As a last, depressing task in the alcohol business, islanders poured the warehouses’ remaining pints and liter bottles of whiskey, one by one, into the barrels which were shipped back to Montreal and Windsor for reblending and future legal sale throughout North America. In a final acknowledgment that the party was over, thousands of empty whiskey bottles were dumped unceremoniously off shore.

For the people of St. Pierre and Miquelon, an economic hangover remained. Okrent says, “Fathers and sons had worked alongside as they loaded and unloaded liquor. They had forgotten how to fish. The islands endured much economic suffering and uncertainty.” Andrieux says there was even an uprising as islanders struggled to cope with the abrupt end to the good times.

Many islanders departed their homeland, but most returned gradually to cod fishing. Things perked up after World War Two when a fish-packing plant opened, bringing an influx of foreign fishing vessels from the Grand Banks to St. Pierre’s port. Tourism also became an important business. Few traces of Prohibition remain, but today visitors come to St. Pierre and Miquelon expressly seeking out the reminders of those few glorious years.