What Does the Future of the Euphrates Spell for the Middle East?

In the wake of the war against Isis in Iraq, an ominous journey along the once-mighty river finds a new crisis lurking in the shallows

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/9b/ae9ba9a5-4534-400b-910c-eff6cdbfae35/dec2017_b08_euphrates.jpg)

Mohamed Fadel led me in the 110-degree heat through the Ishtar Gate, a soaring blue replica of the original made of blue enamel-glazed bricks and covered with bas-reliefs depicting dragons and bulls. We descended a stone staircase and walked along the Processional Way, the main promenade through ancient Babylon. Fifteen-foot-high mud-brick walls dating back 2,600 years lined both sides of the crumbled thoroughfare, ornamented by original friezes of lions and snake-dragons, symbol of the god Marduk, and carved with cuneiform inscriptions. “They brought down the building material for the promenade by boats along the river,” Fadel, an archaeologist, told me, mopping his forehead in the torpor of the July afternoon. The Euphrates cut right through the heart of the ancient city, he explained. Steep embankments on both sides provided protection from seasonal flooding. Just north of the metropolis flowed Iraq’s other great river, the Tigris, joined to the Euphrates by a latticework of waterways that irrigated the land, creating an agricultural bounty and contributing to Babylon’s unparalleled wealth.

It was here, 3,770 years ago, that King Hammurabi codified one of the world’s earliest systems of laws, erected massive walls, built opulent temples and united all of Mesopotamia, the “land between the rivers.” Nebuchadnezzar II, perhaps the city’s most powerful ruler, conquered Jerusalem in 597 B.C. and marched the Jews into captivity (giving rise to the verse from the 137th Psalm: “By the rivers of Babylon / There we sat down and wept / When we remembered Zion”). He also created the Hanging Gardens, those tiered, lavishly watered terraces regarded as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. “In magnificence, there is no other city that approaches [Babylon],” the Greek historian Herodotus declared.

Back in Babylon’s prime, this stretch of the river was a showpiece of water management. “In marching through the country of Babylon,” the scholar Edward Spelman wrote, describing the campaigns of Persia’s Cyrus the Great, “they came to the canals which were cut between the Tigris and the Euphrates, in order, as most [ancient]authors agree, to circulate the waters of the latter, which would otherwise drown all the adjacent country, when the snows melt upon the Armenian mountains.” Edgar J. Banks, an American diplomat and archaeologist, writing of ancient Babylon in 1913, noted that “great canals, as large as rivers, ran parallel with the Tigris and Euphrates, and scores of others intersected the valley, connecting the two streams. There was scarcely a corner of the entire country,” he continued, “which was not well watered; and more than that, the canals served as waterways for the transportation of the crops.”

These days, though, there’s barely enough water to float a canoe. “There are bridges, there is garbage,” said Oday Rais, a major in the Iraqi River Police, as he revved up the outboard motor of his 15-foot patrol boat and steered us toward the center of the stream, nearly running aground in the mud. The waterway was barely 100 feet wide, murky green and sluggish, and the extreme summer heat and absence of rain had reduced it even more than usual. “It is not clean, and the water level is way down. It is not good for navigation.”

This was vivid confirmation of a growing crisis. A recent NASA-German government satellite study found that the Tigris-Euphrates basin is losing groundwater faster than any other place on earth except India. The World Resources Institute, the U.S.-based environmental group, has ranked Iraq as among the nations predicted to undergo “extremely high” water stress by 2040, meaning more than 80 percent of the water available for agricultural, domestic and industrial use will be taken out each year. “By the 2020s,” Moutaz Al-Dabbas, a professor of water resources and the environment at the University of Baghdad, told me, “there will be no water at all during the summer in the Euphrates. It will be an environmental catastrophe.”

For thousands of years Iraq’s fate has depended on the Euphrates, and that is still true, though this simple historical reality is easy to forget after the last few decades of despotism, war and terrorism. The serious problems that increasingly beset the Euphrates receive little attention, as if they were minor annoyances that could be faced later, once the shooting is over.

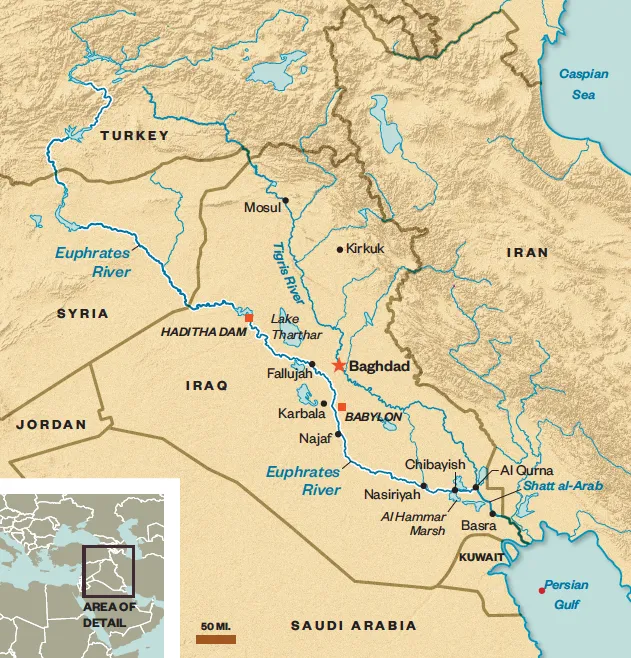

But if there’s a new frontier in political science, it’s the realization that environmental problems, particularly water shortages, not only worsen conflict but may actually cause it. The Euphrates is Exhibit A. In Syria, a devastating drought in the Euphrates Valley beginning in 2006 forced farmers to abandon their fields and migrate to urban centers; many observers believe that the migration fed opposition to Bashar al-Assad and sparked the civil war, in which nearly 500,000 people have died. “You had a lot of angry, unemployed men helping to trigger a revolution,” says Aaron Wolf, a water management expert at Oregon State University, who frequently visits the Middle East. Iraq, like Syria, depends on the Euphrates for much of its food, water and industry. The Haditha Dam in the vicinity of the Syrian border supplies 30 percent of Iraq’s electricity; the Euphrates accounts for 35 percent of the country’s water resources.

I went to Iraq this past summer to find out what kind of shape the nation and its people were in after ISIS was pushed out of the northern city of Mosul, its last major stronghold in Iraq. I decided to use the Euphrates as my guide, since the river had shaped the nation’s history and would literally take me to key places—past the holy Shia cities of Najaf, Karbala and Kufa, through Fallujah and Babylon, down to Basra, a center of oil production.

The more I traveled, the more the river asserted its importance. What did its decline mean for the nation’s future? To Americans, the question might seem impossibly distant. But if the Euphrates continues to deteriorate, the resulting economic stress, dislocations and conflict are all but certain to draw in the United States.

The longest waterway in Western Asia, the Euphrates runs 1,700 miles from the mountains of eastern Turkey to the Persian Gulf. It winds through Iraq for 660 miles. From the Syrian border to the Haditha Dam, a nearly 100-mile stretch, the river traverses dangerous territory harboring ISIS cells that managed to escape the Iraqi Army. And so I began in a city that haunts my memory—Fallujah.

**********

The Euphrates has been central to Fallujah’s identity for millennia. The city’s strategic position on the river drew a procession of invaders, from the Persians to the Romans, who attacked Fallujah in the third century A.D. Caravans from Arabia stopped in Fallujah to water their camels in the river en route to the Mediterranean. Uday and Qusay Hussein, sons of the Iraqi despot, built villas near the Euphrates and constructed an artificial lake drawing water from the river. In 1995, Saddam Hussein built one of his 81 palaces in Iraq overlooking the Euphrates in Fallujah.

In the years after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq and the installation of a Shia-dominated government, Fallujah, a deeply religious city of 300,000 in the Sunni heartland 200 miles southeast of Syria and 40 miles west of Baghdad, became a stronghold of the anti-U.S. insurgency. On March 31, 2004, four American contractors from the military security company Blackwater lost their way in the city while escorting a convoy of food trucks. A mob dragged the contractors from their vehicle, killed them and strung at least two of their burned bodies from the girders of a bridge spanning the Euphrates. The widely disseminated photographs of the victims became symbols of an American quagmire. Over the next eight months, U.S. Marines invaded Fallujah twice, taking hundreds of casualties and nearly leveling the city.

As a Newsweek correspondent, I visited the bridge weeks after the murders, lingering for several minutes before my driver warned me that insurgents were in the area. A week later, I foolishly returned, was seized at gunpoint, accused of being a CIA agent and threatened with execution. My captors, local militants outraged by civilian deaths resulting from American military operations in the city, drove me from safe house to safe house and interrogated me. I was warned that Al Qaeda terrorists were in the neighborhood and would slaughter me if they learned I was here. My Iraqi driver and fixer were forced to bathe in preparation for their executions. At last, after nine hours, a Palestinian journalist I knew who had close relationships with the insurgents vouched for me, and my captors set me and my Iraqi staff free.

Thirteen years later, I wanted to see the bridge again. As I walked along the riverbank at sunset, on the day before the end of Ramadan, the scene of my recurring nightmare couldn’t have been more tranquil. Dozens of boys and teenagers were massed on a steep stone-and-concrete embankment, leaping into the olive-green Euphrates and letting it sweep them downstream. One boy climbed atop the bridge and, as soldiers looked on, jumped into the water 20 feet below.

I chatted with a 12-year-old and asked him about life during the two and a half years the city was controlled by the Islamic State, which seized Fallujah in January 2014, executed soldiers and police, and enforced Sharia law. The boy showed me scars on his back from a whipping he’d received because his uncle was a police officer. “They couldn’t find him, so they found me,” he said. The river, he said, was a no-go area in those days: “Daesh [a disparaging Arabic term for the group] considered swimming a waste of time, a distraction from God,” the boy said. During their occupation, the terrorists did find plenty of uses for the river, however. They sealed off a dam 30 miles upstream to cut water to the rest of Anbar Province, and then opened the dam to flood fields and inflict punishment on civilians. Iraqi security forces, backed by Shia militias, finally drove the Islamic State out of Fallujah in the summer of 2016. Hundreds of Iraqis braved the current to escape ISIS in the battle’s final days, and several of them drowned.

Sheik Abdul-Rahman al-Zubaie, a tall, distinguished-looking Sunni leader in Fallujah who fled when ISIS took over and returned this past April, told me that the quality of life has improved immeasurably. “The people are out in the streets, the kids are jumping in the river. It is a huge change, it’s incomparable with Daesh’s time,” he told me, watching the boys playing on the riverbank at sunset. But al-Zubaie remained deeply distrustful of the Shia-dominated government, which, he says, has neglected Fallujah and abused its citizens. “We are trying to create this [rebirth] by ourselves,” he said. “We’re not getting much help from Baghdad.”

The Iraqi security forces guarding the town, most of them Shias, don’t feel comfortable here either. A year after the Islamic State fled the city, the Euphrates remained closed to boat traffic—partly because the troops fear that Islamic State sleeper cells could launch a sneak attack from the river.

**********

The river was a conduit for the religious warriors who spread Islam across the Middle East. In A.D. 656, Ali ibn Abi Talib, the son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad, moved the capital of his caliphate from Medina to Kufa, on the Euphrates south of Babylon. Kufa abounded with fertile fields of wheat, date palms, rice and other crops extending for miles from both banks. “The Euphrates is the master of all rivers in this world and in the hereafter,” Imam Ali declared.

In Kufa, I met Mohammed Shukur Mahmoud, a grizzled former merchant marine who operates a water taxi among a handful of villages along the river. He steered his outboard boat into the Euphrates toward the Imam Ali Bridge. The two branches of the Euphrates join a few miles upstream from here, but if anything, the river’s flow is even weaker than it was in Babylon. As he neared the bridge’s concrete supports, he abruptly turned the boat around; the river was too muddy and filled with silt to continue. “In the past, it was a lot clearer and a lot deeper. I remember we could freely go anywhere,” he said, returning the boat to the dock after a 45-minute cruise. Shukur recalled the “better times” before the First Gulf War in 1990, when he served as an officer in the Iraqi merchant marine, piloting “big ships that stopped in ports all over Europe.” Those Saddam-era vessels were in ruins now, he says, and he has been eking out a living in a stream that has been drying out before his eyes. “I wish I could take you longer, but I don’t trust the river,” he told me apologetically as he dropped me at the dock.

The Euphrates’ problems begin more than 1,000 miles upstream, near the river’s catchment area below the Taurus Mountains in eastern Turkey. In a headlong rush to generate electricity and create arable land, the Turkish government has been on a dam-building boom for two generations. In 1974 the Keban Dam was opened on the Upper Euphrates. The Ataturk Dam was finished in 1990. The ongoing Southeastern Anatolia Project, a $32 billion scheme to build 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric plants on both the Tigris and the Euphrates, will eventually provide nearly one-quarter of Turkey’s electricity. Syria, meanwhile, built the Tabqa Dam upstream from Raqqa in the 1970s, and added a few more dams on the Euphrates and its tributaries before the civil war ground development to a halt. Since the Turkish and Syrian dams began operating in the 1970s, the water flow into Iraq has dropped by nearly two-thirds.

For decades Iraq has been squabbling with both neighbors about getting its fair share of the water. The dispute nearly flared into violence in the early 1970s, after Turkey and Syria diverted the Euphrates into a series of reservoirs and nearly dried out the river downstream in Iraq. In response the Iraqi government constructed a series of canals linking the Euphrates to Lake Tharthar, a reservoir northwest of Baghdad. With talks long frozen, Iraq has been dependent on oft-disputed arrangements with its upstream partners. “Turkey will give us some water, but it’s mostly wastewater and irrigation spill-off,” says Moutaz Al-Dabbas, the Baghdad University water resources expert. “The quality is not the same as before.”

Global warming is adding to Iraq’s woes. Decreased rainfall totals have already been recorded throughout the Euphrates Basin. By the end of this century, according to some climate models, the average temperature in the river basin is likely to increase by 5 to 7 degrees Fahrenheit, which would cause higher rates of evaporation and an additional 30 to 40 percent decline in rainfall. (Iraqis I met along the river complained that the summers have grown noticeably less bearable in recent years, with the midday temperature rarely dropping below 111 degrees Fahrenheit between June and September.) A 2013 study by the World Resources Institute projected that by 2025, Iraq’s water outlook will be “exceptionally more stressed.” In other words, the researchers said, “basic services (e.g. power, drinking water distribution) are likely at risk and require significant intervention and major sustained investments.”

**********

It was not far downstream from where we docked the boat that Imam Ali was killed in 661. While Ali was saying the dawn prayer at Ramadan at the Grand Mosque of Kufa, an assassin from the Kharijite sect cleaved his skull with a poisoned sword. A new caliph claimed power in Damascus—Muawiya, the aging scion of the Umayyad clan—but Ali’s son, Imam Hussein, insisted that the right to lead the caliphate belonged to the descendants of the prophet. Hussein’s adherents, the Shias, and those loyal to the caliph in Damascus, the Sunnis, have been at odds ever since, a conflict that continues to divide Iraq, and much of the Middle East, to this day.

I reached Najaf, one of the most sacred cities in the Shia world, on the first morning of Eid al-Fitr, the several days-long celebration of the end of Ramadan. Three miles southwest of Kufa, Najaf now displays ubiquitous signatures of its blood-soaked past. Posters displaying Shia militiamen killed in battles against the Islamic State hang from nearly every utility pole. Suspended alongside them are placards showing spiritual leaders who died martyrs’ deaths: Muhammed Bakr al-Sadr, an influential cleric executed by Saddam Hussein in 1980; his cousin, Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Sadeq al-Sadr, gunned down with two sons as he drove through Najaf in 1999; and Ayatollah Mohammad Baqir al-Hakim, blown up with 100 others in an Al Qaeda car bomb attack in front of the Imam Ali Shrine in August 2003.

Just before I arrived in Najaf, a Daesh suicide bomber had been shot dead at a checkpoint. With the temperature nearing 115, we entered the old city, a maze of alleys packed with pilgrims heading for the shrine, where the first Shia martyr, Imam Ali, lies buried. Women in black abayas and men in white dishdashas gulped down water at roadside stands; hundreds were lined up to see Ayatollah Sistani, whose home stands just outside the shrine. As I walked amid the crowds in the sizzling heat, I felt a wave of fear: The holiest Shia city in Iraq on one of the most sacred days of the Muslim calendar seemed an inviting target for a terrorist attack.

We entered the complex through the Al-Kibla Gate, a Moorish-style archway adorned with blue mosaics. As I passed through a metal detector, I looked up to see the gold-covered dome and minaret of the tenth-century shrine looming in front of me. I removed my shoes, walked across an inner courtyard filled with resting pilgrims, and, along with a throng of celebrants, passed through another arch into Imam Ali’s tomb. Crystal chandeliers cast a dazzling light on the gold-and-silver crypt that contained his marble coffin. Hundreds of worshipers pressed their faces against the screened crypt, murmured prayers and raised their hands in supplication. I stepped back into the street, cast a wary eye around me and rushed to our car, relieved that the visit had gone off without incident.

Najaf was nearly abandoned in the 17th century after the Euphrates shifted course, but in the early 1800s Iraq’s Ottoman rulers dug the Hindiya Canal, which channeled the river back to Najaf and restored the city’s fortunes. Its holy men began to wield great power in the area, and Najaf asserted itself as one of the most important centers of Shia Islam.

One of the lessons of the Euphrates in Najaf is that Iraq’s own wasteful water practices bear some blame for the river’s dangerously diminished condition. The government of Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has begged farmers around the holy Shia city to stop planting rice, which grows in flooded fields between June and November and requires up to three times the water used for maize and barley. But the farmers, says Moutaz Al-Dabbas, “have ignored him.” Now, as the river declines, Najaf’s dependence on rice is looking increasingly like a bad bet: In 2015, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Iraq’s rice output, nearly all of it around Najaf, plummeted by almost 60 percent from the year before. Many irrigation channels from the river had run completely dry.

**********

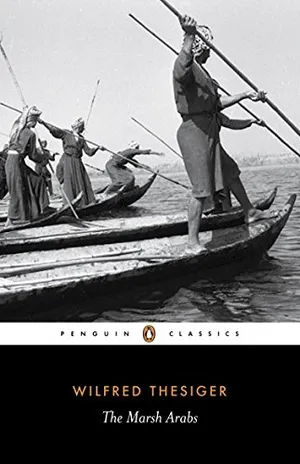

South of Nasiriyah, the site of a bloody battle between Saddam’s fedayeen and U.S. forces in March 2003, the Euphrates divides into dozens of narrow branches. This is the Al Hammar Marsh, a 7,700-square-mile aquatic zone in the desert that the British travel writer Wilfred Thesiger described in his 1964 classic The Marsh Arabs. He wrote of “stars reflected in dark water, the croaking of frogs, canoes coming home at evening, peace and continuity, the stillness of a world that never knew an engine.” After the 1991 Shia revolt, Saddam in retaliation erected dams that diverted the Euphrates and starved the marshes; the population fled, resettling in Iran and southern Iraqi cities.

After the dictator’s fall, locals removed the obstructions and the water flowed back in. I had visited the marshes in 2003 and again in 2006, when the place was just being settled again. At the time, the water level was still low, infrastructure was nonexistent, and the Mahdi Army, the Shia militia organized by Muqtada al-Sadr, the son of the murdered Grand Ayatollah al-Sadr, had declared war on the U.S. and Britain, making travel dangerous.

Now, a decade later, I wanted to see whether anything had improved. A large poster showing the decapitated, blood-soaked head of Imam Hussein greeted us as we entered the town of Chibayish, in the heart of the Al Hammar Marsh. We arrived at the main canal marking the town’s eastern border. “This channel was dry before 2003,” Khalid al-Nasiri, a local official, told me. “You could walk across it. And now it’s four meters deep.”

With al-Nasiri and two other municipal officials, we set out from the dock in two 20-foot-long motorboats, passed beneath a bridge, then picked up speed. Water buffaloes lolled in the milky water. A fisherman casting his net looked up in surprise. “Where are you going in this heat?” he asked. The channel narrowed, human settlement disappeared, and thick groves of reeds rose on both sides. Pied kingfishers, Basra reed warblers, African darters, sacred ibises and other colorful water birds exploded out of the foliage as our boat skipped past.

After five days in the dry, dusty landscapes of central Iraq, I was elated to be in this lush and seemingly pristine water world. We followed channels through the tall marsh grass for an hour, stopping briefly in a lagoonlike cul-de-sac for a swim. A cluster of mudhifs—slightly curved marsh dwellings made of woven reeds—appeared on the muddy shore, alongside a herd of snorting water buffalo, nearly submerged in the water. We moored the boats and clambered out. In the stillness and shadelessness of the afternoon, the 120-degree heat assaulted me like a blast from a furnace.

The Marsh Arabs (Penguin Classics)

Wilfred Thesiger's magnificent account of his time spent among them is a moving testament to their now threatened culture and the landscape they inhabit.

Haider Hamid, a rail-thin man in a white dishdasha, stood on the shore watching our arrival, wiping the sweat from his face. At first he said he was too fatigued to talk, but he soon reconsidered. He was 5 years old when Saddam drained the marshes, he recalled, forcing his family to resettle in Amarah. A year later his father, a Shia activist, was gunned down by a Saddam hit squad while praying in a mosque, leaving Hamid and his four brothers to be brought up by their mother. In 2003, they returned to the marsh, raising water buffalo, which they sell to merchants who drive to their settlement along a pitted asphalt road through the reeds.

Inside the mudhif, soft light filtered through the thatch, illuminating half a dozen boys sitting on the floor. They were eating from a communal plate of rice and buffalo meat. A generator powered a flat-screen television set, which was airing a daytime soap opera. Beneath a colorful poster of Imam Hussein, against the rear wall, a cooler hummed. In this isolated corner of Iraq, modernity was creeping in.

But development fell far short of Hamid’s expectations. None of the boys in this small settlement were in school; the nearest school was in Chibayish, an hour away, and they had no means of getting there. “People left the marshes, joined the Hashd al-Shaabi, got government jobs, because life conditions here are very hard,” he said.

Al-Nasiri, the local official, explained that the marsh population was too scattered to make electrification and local schools practical.

A larger issue for the viability of this way of life is the condition of the river itself. In the five years after Saddam’s fall, the wetlands regained 75 percent of their original surface area, but now that has shrunk to about 58 percent, and it is continuing to constrict. Severe droughts in 2008 and 2015 nearly dried out the marshes, and erratic water flows have greatly reduced fishing stocks. “Last year they opened the Mosul Dam, and people said, ‘We have so much water.’ But when the summer comes, there’s almost no water,” Moutaz Al-Dabbas, the environmental expert, had told me. “You need a constant flow, and that doesn’t exist.”

Plenty of other problems threaten the wetlands: Evaporation and the dumping of irrigation runoff into the river have greatly increased salinity levels, sapping marsh grass of nutrients and cutting the productivity of water buffalo for milk and meat—a critical income source for much of the population here. Valuable fish species, such as gatans, have vanished. Many local residents now cook with and drink bottled water, rather than water taken directly from the marshes.

Hamid was determined to stay put. “Although I moved to the city [after Saddam drained the marshes], this is how we grew up, how we were raised by our father,” he told me, as we boarded the boats for the return journey to Chibayish. “We are trying our best to keep it alive.”

**********

The Euphrates meets the Tigris in the dusty town of Al Qurna, 30 miles east of Chibayish. Here the two great rivers become the Shatt al-Arab, which gains force and breadth as it flows to the Persian Gulf. I sat on the deck of a slender wooden skiff in Basra, motoring down the quarter-mile-wide waterway past fishing boats and pleasure craft. It was dusk and the multicolored lights of Basra’s sheeshah bars reflected off the water. We passed the illuminated sand-colored gate of Saddam’s riverfront palace, controlled by the Hashd al-Shaabi, the most powerful force in Iraq’s second city. Our boatman, Ali Saleh, gunned the engine and raced between the supports of a new concrete bridge, kicking up a wake. “In the 1970s my father used to take a big metal boat to transfer wheat and seeds to Baghdad up the Shatt,” he told me. The shrinking of the Euphrates upstream made such long journeys impossible, but Saleh had often cruised downstream to the mouth of the river, a nine-hour trip.

Yet the relative health of the river here is illusory. A few years ago, Iran blocked off both tributaries that flow into the Shatt al-Arab. That prevented fresh water from washing out salt tides from the gulf and dramatically raised the river’s salinity. The salt water destroyed henna plantations in Al-Faw, once a major income source, and killed off millions of date-palm trees. Fish species on the river have changed, and a coral reef has grown at the entrance to the Shatt al-Arab. “When they changed the salinity, they changed the whole environment,” Al-Dabbas told me.

Basra, too, presents a disquieting picture. The province’s oil wells are pumping three million barrels a day, up more than 60 percent from 2011. Iraq ranks second among OPEC producers, and 780 oil companies, ranging from giants like Royal Dutch Shell and British Petroleum to small service firms, are doing business here. The oil boom has financed hotels, shopping malls and McMansions. But corruption is endemic, and the gap between wealthy and poor is widening. Crime syndicates tied to Shia parties and militias have siphoned away billions of dollars by extorting bribes, taking kickbacks on contracts and stealing oil. A few years ago, according to watchdog groups in Basra, the mafias ran 62 floating docks at the Basra port, using them to loot half the total oil production. The government has hired extra guards and tightened security. “Now billions aren’t being wasted, just tens of millions,” said Ali Shadad Al Fares, head of the oil and gas committee in the Basra provincial council, who acts as a liaison to the big oil producers. “So things are improving.”

For most, they’re not. Countless migrants who have flooded to Basra in recent years in search of economic opportunities have been disappointed. The outskirts of the city are now covered with squatter camps—an unbroken sea of cinder-block huts and fetid, garbage-strewn canals, afflicted by frequent power cuts and baking in a miasma of summer heat. The taxi driver who took me past the makeshift settlements called Basra “the richest town in the world, and nothing for us has improved.”

These same squatter camps provided the cannon fodder for the war against the Islamic State: thousands of young Shias filled with frustration and inspired by Ayatollah Sistani’s call for jihad. As I walked past the placards of Shia martyrs on Basra’s streets, I realized that the war against Daesh, seemingly distant, was a trauma that had damaged the whole country. Sunnis fear the Hashd al-Shaabi and believe that the war against Daesh has given them unchecked power to commit abuses. The Shia tend to view the entire Sunni population as complicit in Daesh’s war. It was an “ideological battle under the name of Islam to eliminate the Shia and destroy their holy sites,” Fadel al-Bedeiri, the Shia leader, had told me as we sat in his office on a back alley in Najaf. “Iraq’s problem is the Shia struggle for power, a fact [challenged] by Sunnis. As long as this struggle exists, Iraq will never be healed.”

**********

Al-Bedeiri’s words proved prophetic. Two months after I met with him, he survived an assassination attempt after unidentified men attacked his convoy with hand grenades as he was leaving evening prayers at a mosque in Najaf. The militiamen, believed to be affiliated with Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shia militant group and political party, were apparently out to punish al-Bedeiri, sources told me, because he had opposed a deal between Hezbollah and Syria to give safe passage to ISIS prisoners to a sanctuary near Syria’s border with Iraq. Al-Bedeiri thought that the deal—which Syria and Hezbollah had agreed to in exchange for the hand-over of the remains of nine Lebanese soldiers killed by ISIS in 2014—would endanger Iraq’s security. His close call was another reminder of the turbulence and sectarian strife—and even Shia-on-Shia violence—that continues to convulse the region.

The seemingly endless fight against ISIS, and the massive psychic and physical damage inflicted on Iraq over years of conflict, mean that seemingly less urgent challenges—such as saving the Euphrates—are likely to remain neglected. “The people are not thinking about the water, they are thinking about the war,” Al-Dabbas acknowledged sadly as we sat in the lobby of my hotel in Baghdad, an air-conditioned sanctuary from the 123-degree heat. It was time, he said, for the government to swing into action. The Euphrates needed “good management, legislation and enforcement,” he told me, if it was to be saved. It needed “a third party, like the USA,” to help drag Turkey and Syria to the bargaining table to work out a deal for equitable distribution of upstream water.

Without these things, he fears, the Euphrates will soon be reduced to a barren, dusty riverbed, and the countless Iraqis who depend on it will find their very survival jeopardized. “This is a crisis,” he said, “but nobody is paying attention to it.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)