The Brain-Freezing Science of the Slurpee

More than 60 years ago, a broken soda fountain led to this cool invention

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/f4/64f4e50f-b8d2-4508-b0c3-2794d3aa334f/slurpee_copy.jpg)

It’s cold. It’s fizzy. It’s sickly sweet. It’ll make you grab your head in pain if you drink it too fast. It’s the Slurpee (or ICEE, depending on where you purchase it).

These frosty concoctions came about one hot day during the late 1950s when Dairy Queen owner Omar Knedlik was desperate for cold beverages to serve. Omar was a World War II veteran and had a strong entrepreneurial sense. When he returned from the war, he used his military pay to purchase his first ice cream shop in Belleville, Kansas. Several business ventures later, he bought the Dairy Queen in Coffeyville, a city in the state’s southeast corner.

But the store didn’t come without its kinks—his soda fountain broke, leaving Knedlik without cold drinks in the Kansas heat. So he sent away for bottles of soda and plunged them into the frosty depths of his freezer to chill for his thirsty customers. When he popped the lids, the sodas instantly turned slushy, says Phil Knedlik, one of Omar’s two sons.

Though it sounds like a party trick, this actually involves some flashy chemistry. There are likely a few factors at work here, but one of the most important is the formation of what is known as a supercooled liquid. This means, that the drink is actually colder than the point at which the solution transforms into ice—but not frozen yet.

This can happen because for ice to form, it needs somewhere to start—a rough spot in the glass or even a flake of dust. Without it, the water just keeps chilling. When you open a bottle of supercooled soda, the bubbles of carbon dioxide begin to fizzle out, providing plenty of surfaces for ice to form, creating a refreshingly light and slushy beverage. Try it for yourself.

The slushy sodas made a splash. “A lot of people said, ‘hey, I’d like to have one of those [sodas] that when you pop the lid the whole thing freezes,’” says Phil.

Though Omar replaced his soda fountains, the idea of frozen sodas still brewed in his head. “He kept thinking about that old soda pop machine breaking down,” says Phil. “And that gave him the idea.”

Omar fiddled with an old Taylor ice cream maker to recreate the frosty brew. Soon, he came up with a basic machine for making frozen soda, says Phil. But he continued to tinker with it for several years to get the fluffy slush just right. Omar hired the artist Ruth Taylor to dream up the brand. She named the drink “ICEE” and created a logo. His first flavor: cola.

The chemistry of these frozen concoctions is actually more complex than you may think. The solution of flavor syrup, water and carbon dioxide starts out in a barrel, where it is chilled under pressure. An auger churns the solution to keep it moving, scraping away any ice that forms on the container sides.

The constant movement and syrupy sugars keep the solution from freezing into a solid log—interestingly, no one has yet figured out how to make a sugar-free ICEE. When a customer pulls down the handle, out comes the semi-frozen foam, which appears to puff up and solidify as it fills the cup.

An ICEE is a little bit like an avalanche. “If you are in an avalanche, it’s sort of like you’re swimming around in snow,” explains Scott Rankin, a food scientist at University of Wisconsin-Madison. “As soon as the avalanche stops, it becomes very rigid, very cement-like.”

Similarly, when the ICEE is mixed in the chamber, the motion prevents ice particles from binding together. But once the avalanche of frosty sugary drink enters the cup, the motion stops, allowing the ice to bind together and solidify.

Something else, however, could also be at work, says Richard Hartel, a food engineering professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. When the semi-frozen solution leaves the tap, it appears to puff up and form more ice crystals. This extra oomph of frost may come from the so-called Joules-Thomson effect. When gas expands, it absorbs heat, cooling the surrounding solution. So as the ICEE comes out of the tap, the dissolved carbon dioxide starts to escape, both puffing up and further freezing the solution.

When ICEE first hit the market, word of mouth drew crowds to Omar’s shop. “Some of my fondest memories are working in the Dairy Queen store,” says Phil, “meeting all the people and seeing the big long lines of people waiting on the ICEE machine to catch up.”

That first machine had two taps. One was usually Coke, and the other was a rotating array of flavors—root beer, Dr. Pepper, orange soda. In the early days of ICEE, the machines could make a few drinks at a time, then people had to wait for more soda to freeze.

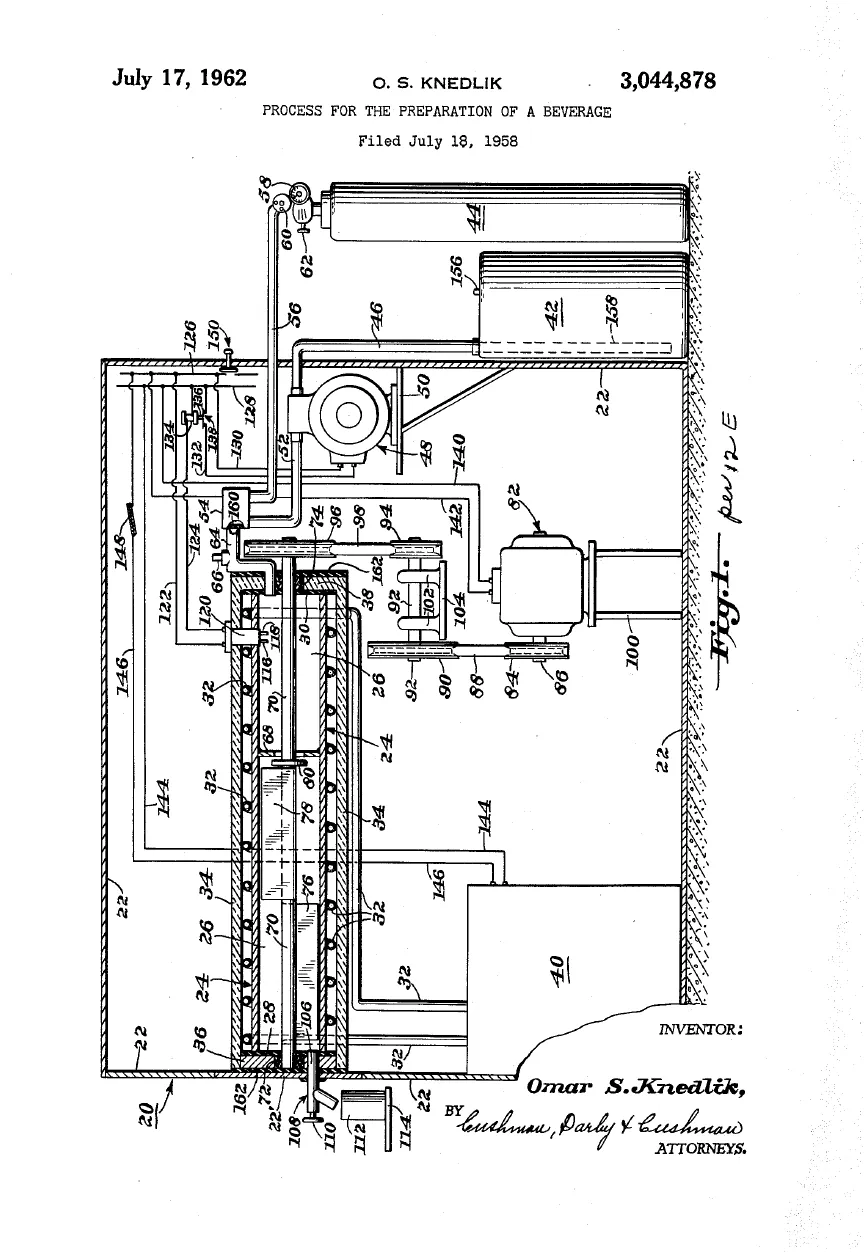

In 1960, Omar teamed up with the John E. Mitchell company to mass produce his invention, eventually patenting it, “The Machine for Dispensing Semi-Frozen Drinks and Control Therefor.”

In 1965, the ICEE craze got the attention of 7-Eleven stores who purchased some of the machines, renaming their frosty brew Slurpee—after the characteristic slurping sound of the drink.

"The first time I heard that sound through a straw, it just came out 'slurp.’" said Bob Stanford, the director of 7-Eleven’s in-house ad agency, in a 1967 meeting. He later explained, "We added the two e’s to make a noun. It was just a fun name and we decided to go with it."

Meanwhile, the ICEE Company forges on, selling the drinks under the ICEE name at other stores, fast food restaurants, cinemas and gas stations in the United States, Canada, Mexico, China and the Middle East.

Now, roughly 60 years after the first ICEE hit the glass and 50 since Slurpee got in the game, the machines produce the frosty foam quicker and more consistently, and in flavors like birthday cake and strawberry shortcake.

Every year 7-Eleven celebrates its birthday on July 11 (or rather, 7/11), giving away millions of free Slurpees to customers. Should you partake, stop and think about the complex chemistry you’re guzzling. The changes in pressure and temperature, and all that sugar, is enough to give anyone a brain freeze.

Editor's note, July 12, 2017: This story has been updated to include an earlier patent from 1962 for the machine invented by Omar Knedlik.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)