A Brief History of the Crock Pot

More than eighty years after it was patented, the Crock Pot remains a comforting presence in American kitchens

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/27/5d/275d5fac-55c3-405c-90cf-04eb3a2a3d37/crock_pot_main.jpg)

When Leeann Wallett reflects on happy days from her childhood, she thinks of New Year’s Eve. Each year, Wallett’s mother would whip up an impressive spread of 1970s-style appetizers. “My mom was never a huge cook,” Wallett recalls, “but when she did cook, it was spectacular.”

The centerpiece of these meals was a miniature Crock Pot called the Crockette, which kept food hot from dinner until the clock struck midnight. The recipes varied from year to year—sometimes tangy-sweet meatballs mixed with pineapple, sometimes cocktail weiners jazzed up with cherry pie filling—but all still strike a deep chord of nostalgia for Wallett, who grew up to become an avid home cook and, in her spare time, a food writer for local and regional outlets in her home state of Delaware.

These memories took on new significance when Wallett’s mother passed away in 2008. The Crockette went into storage for a few years, but eventually, it found its way back into her kitchen. Today, she uses the little Crock Pot to serve warm artichoke dip during football games, and to keep her mother’s memory alive.

Nearly 80 years after its patent was issued, the Crock Pot continues to occupy a warm place in American kitchens and hearts. For Paula Johnson, curator for the Division of Work & Industry at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., the Crock Pot’s ubiquity lends to its charm. When Johnson returns to family potlucks in her own Minnesota hometown, she can count on seeing a long, buffet line of Crock Pots.

“The idea of being able to produce something quickly and without a lot of mess, either prep or clean up, is a time-honored tradition,” Johnson says.

The Crock Pot’s story began during the 19th century in Vilna, a Jewish neighborhood in the city of Vilnius, Lithuania. Once known as the "Jerusalem of the North," Vilna attracted a thriving community of writers and academics. There, Jewish families anticipated the Sabbath by preparing a stew of meat, beans and vegetables on Fridays before nightfall. Ingredients in place, people took their crocks to their towns’ bakeries—specifically, to the still-hot ovens that would slowly cool overnight. By morning, the low-and-slow residual heat would result in a stew known as cholent.

Long before he invented the modern slow cooker, Irving Nachumsohn learned of this tradition from a relative. Nachumsohn was born in New Jersey in 1902, where he joined an older brother, Meyer, and later gained a younger sister, Sadie. His mother, Mary, who immigrated to the U.S. from Russia, left Jersey City for Fargo, North Dakota, after her husband’s death, eventually crossing the border into Winnepeg, Manitoba, to help Meyer avoid being drafted into service during World War I. Irving Nachumsohn grew up to study electrical engineering through a correspondence course, later returning to the United States, specifically Chicago, as Western Electric’s first Jewish engineer.

When he wasn’t at work, Nachumsohn explored his passion for inventing, even passing the patent bar exam himself to avoid hiring a lawyer. With time, Nachumsohn was able to start his own company, Naxon Utilities Corp., where he focused on honing inventions full time.

Nachumsohn’s inventions—such as his electric frying pan and his early version of the modern lava lamp—found traction in stores and homes. His telesign laid the groundwork for the electronic news scrollers that light up major cities, delivering headlines and stock movements to passersby. (The most famous of these is Times Square’s “Zipper.”)

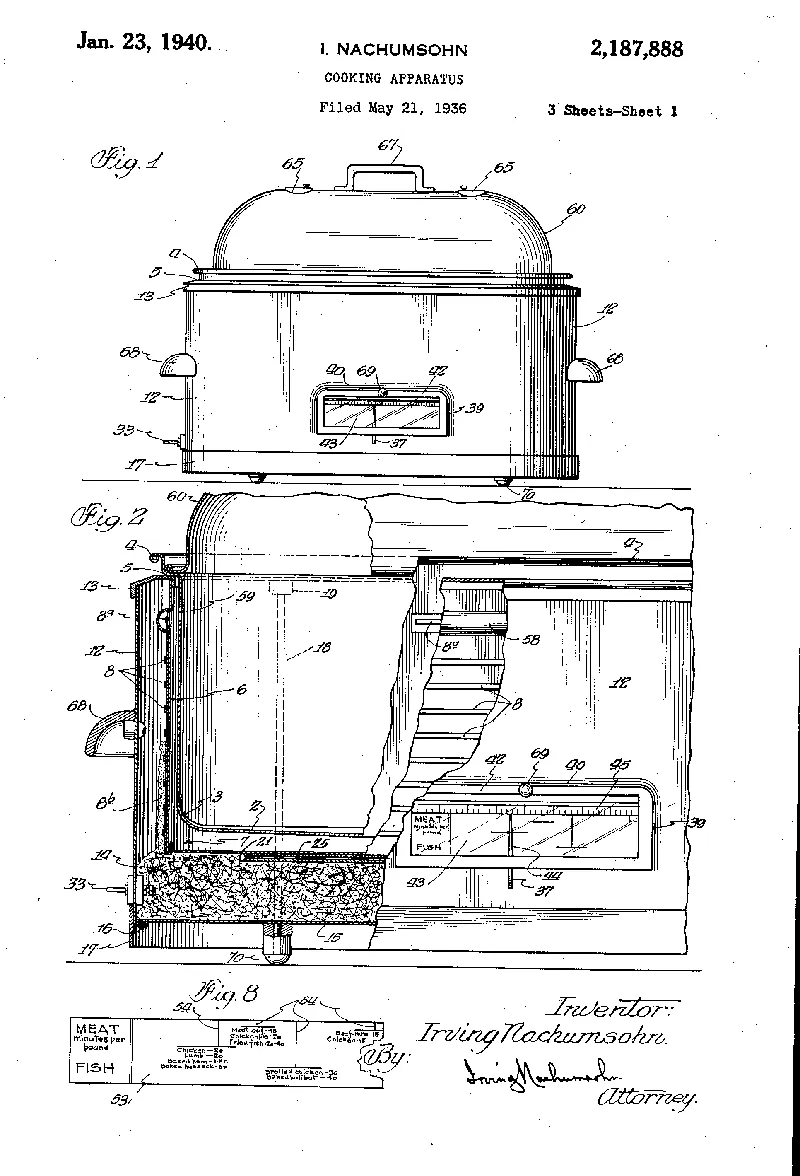

According to Nachumsohn’s daughter, Lenore, her father’s broad range of inventions is evidence of his curiosity and devotion to problem-solving. In their household, the slow cooker was a solution to summer heat, allowing the family to prepare meals without turning on the oven. Nachumsohn applied for the patent on May 21, 1936, and it was granted on January 23, 1940.

Nachumsohn’s slow cooker went to market more than a decade later, during the 1950s, although the reason for this delay is not clear. At the time, the slow cooker seemed unlikely to catapult Nachumsohn to fame, though it did highlight another significant development in his family’s life—a new name. In 1945, World War II put an uncomfortable spotlight on Americans with German names, prompting Nachumsohn to shorten his family’s name to Naxon. This explains why Nachumsohn’s first slow cooker was called the Naxon Beanery, a squat crock with a fitted lid and a heating element built around its inner chamber to promote even cooking.

When Naxon retired in 1970, he sold his business to Kansas City’s Rival Manufacturing for cash—marking a turning point in the Crock Pot’s history. By then, the Naxon Beanery was nearly forgotten, according to then-president Isidore H. Miller. As Rival integrated Naxon Utilities into its larger operations, its team of home economists were tasked with testing the Naxon Beanery’s versatility.

At Chicago’s 1971 National Housewares Show, Rival unveiled its newly rebranded version of the Naxon Beanery. Dubbed the Crock Pot, the appliance received a new name, refreshed appearance and a booklet of professionally-tested recipes. Home cooks eagerly brought their Crock Pots home, in distinctly ‘70s hues like Harvest Gold and Avocado. Advertising campaigns, along with word of mouth, drove sales from $2 million in 1971 to an astounding $93 million four years later.

It was during this initial boom that Robert and Shirley Hunter received their own avocado-toned Crock Pot as a gift. Now on display at the National Museum of American History, the Crock Pot once cooked the Pennsylvania-based family’s favorite meals, like halushki, a hearty Polish dish of cabbage, onion, garlic and noodles.

Those meals—home cooked, comforting and nutritious—form the basis for the Crock Pot’s place in American food culture, Johnson says. The Crock Pot arrived at a poignant moment in America’s evolving relationship to food, as companies pumped time-saving technologies into the market at a rapid clip. The Crock Pot arrived alongside Tupperware, microwaves and frozen dinners, all promising greater convenience for working women and their families. In fact, a 1975 advertisement that ran in the Washington Post explicitly branded the Crock Pot as “perfect for working women.”

At the same time, chefs such as Alice Waters and Julia Child encouraged home cooks to embrace fresh ingredients and professional cooking techniques. Williams-Sonoma had provided home cooks with specialized cookware since 1956, and it was joined in 1972 by the arrival of Sur La Table. The Back to the Land movement rejected processed foods, instead urging Americans to rediscover the value in gardening and artisanal products.

“It’s just part of the bigger context of changes in how we eat in that post-war period,” Johnson says. “There are strands of technology and innovation, and there are also strands of different ideas about producing and preparing food.” The Crock Pot seemed to span both perspectives. “Crock Pot is one of those examples of one brand that really, really resonated with a lot of people around the country,” Johnson adds.

A multi-use appliance, most Crock Pot recipes don’t require any special equipment or knowledge. While some recipes—like the cocktail weiner and cherry pie mixture Wallett remembers—called for heavily processed ingredients, the Crock Pot can also be used to prepare fresh ingredients with a fraction of the effort. Today, modern recipe websites like the Kitchn explicitly marry technology with a Back to the Land mentality by encouraging home cooks to slow cook, then freeze, batches of CSA produce.

Ultimately, the Crock Pot’s legacy is that it encourages cooks of all experience levels to get into the kitchen. “It's a simple device,” Johnson says. “It's hard to go wrong. People who don't have a lot of culinary training can figure it out.”

This widespread appeal continues to drive sales today. According to Statista, Americans purchased 12.7 million slow cookers in 2018. Crock Pots now share a crowded slow cooker market with dozens of competitors, including KitchenAid, Hamilton Beach and Instant Pot, a Canadian pressure cooker that was the most wish-listed item on Amazon in 2017. Still, the Crock Pot remains iconic, reliably nabbing spots on "Best Of” lists by Consumer Reports, New York magazine’s The Strategist and Good Housekeeping.

In a strange twist, the television show This Is Us gave the Crock Pot both a PR crisis and an unexpected boost in sales. In January 2018, the NBC drama revealed a faulty Crock Pot as the cause of a main character’s death. The plot point ignited a storm of social media outrage, even pushing Crock Pot to join Twitter for the first time to defuse the communications crisis.

Despite public blowback, the incident spurred a new wave of sales. According to Mark Renshaw, then Edelman’s global chair of brand practice, Crock Pot sales leapt by $300,892 during the month after the episode aired. (Crock Pot is a client of Edelman, a global PR and marketing firm.)

The Crock Pot’s continued impact is also apparent on AllRecipes, America’s most popular—and revealing—online recipe aggregator. There, amateur cooks and professionals alike have compiled nearly 2,500 recipes designed for slow cookers. In fact, slow cooker recipes are so popular that they command their own category.

At the time of writing, AllRecipes’ most popular slow cooker meal was a version of Salisbury steak, made with lean ground beef, Italian breadcrumbs and a packet of onion soup mix. More than 5,000 people have made it, generating hundreds of comments and photos. “This recipe is our ‘go-to’ for busy days,” one reviewer praised.

For Wallett, too, slow cooker recipes save time and energy. During the final month of her pregnancy last summer, Wallett prepared and froze dozens of scratch-cooked meals. These days, she’s more likely to reach for her Crock Pot or Instant Pot to make an easy dinner while caring for her newborn son.

“Now that he's here, I always want to do those dump meals, where you dump everything in the slow cooker and just let it go,” Wallett says, laughing. “In between naps, I can sauté onions and everything, then throw it all in the Crock Pot.”

Wallett’s vintage Crockette is still going strong, though she now reserves it for special occasions. Maybe one day, she’ll pass it down, too.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michelle.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michelle.png)