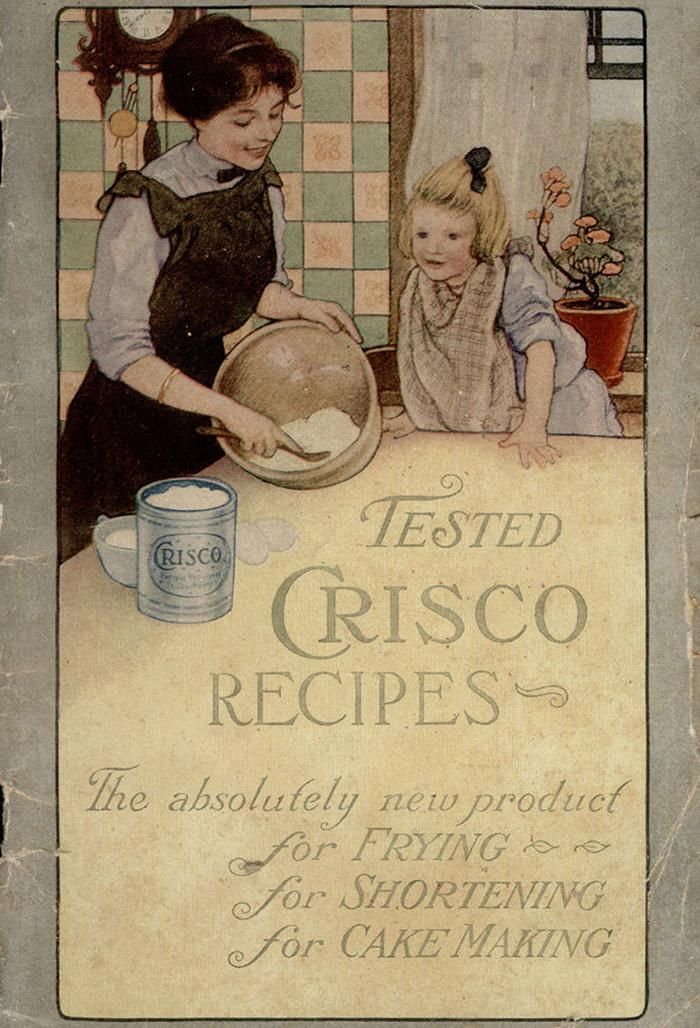

How Crisco Made Americans Believers in Industrial Food

Crisco’s main ingredient, cottonseed oil, had a bad rap. So marketers decided to focus on the ‘purity’ of factory food processing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/5f/705f2c5c-77d0-4180-8570-f3dfbf6dbd61/crisco_tubs.jpg)

Perhaps you’ll unearth a can of Crisco for the holiday baking season. If so, you’ll be one of millions of Americans who have, for generations, used it to make cookies, cakes, pie crusts and more.

But for all Crisco’s popularity, what exactly is that thick, white substance in the can?

If you’re not sure, you’re not alone.

For decades, Crisco had only one ingredient, cottonseed oil. But most consumers never knew that. That ignorance was no accident.

A century ago, Crisco’s marketers pioneered revolutionary advertising techniques that encouraged consumers not to worry about ingredients and instead to put their trust in reliable brands. It was a successful strategy that other companies would eventually copy.

Lard gets some competition

For most of the 19th century, cotton seeds were a nuisance. When cotton gins combed the South’s ballooning cotton harvests to produce clean fiber, they left mountains of seeds behind. Early attempts to mill those seeds resulted in oil that was unappealingly dark and smelly. Many farmers just let their piles of cottonseed rot.

It was only after a chemist named David Wesson pioneered industrial bleaching and deodorizing techniques in the late 19th century that cottonseed oil became clear, tasteless and neutral-smelling enough to appeal to consumers. Soon, companies were selling cottonseed oil by itself as a liquid or mixing it with animal fats to make cheap, solid shortenings, sold in pails to resemble lard.

Shortening’s main rival was lard. Earlier generations of Americans had produced lard at home after autumn pig slaughters, but by the late 19th century meat processing companies were making lard on an industrial scale. Lard had a noticeable pork taste, but there’s not much evidence that 19th-century Americans objected to it, even in cakes and pies. Instead, its issue was cost. While lard prices stayed relatively high through the early 20th century, cottonseed oil was abundant and cheap.

Americans, at the time, overwhelmingly associated cotton with dresses, shirts and napkins, not food.

Nonetheless, early cottonseed oil and shortening companies went out of their way to highlight their connection to cotton. They touted the transformation of cottonseed from pesky leftover to useful consumer product as a mark of ingenuity and progress. Brands like Cottolene and Cotosuet drew attention to cotton with their names and by incorporating images of cotton in their advertising.

King Crisco

When Crisco launched in 1911, it did things differently.

Like other brands, it was made from cottonseed. But it was also a new kind of fat – the world’s first solid shortening made entirely from a once-liquid plant oil. Instead of solidifying cottonseed oil by mixing it with animal fat like the other brands, Crisco used a brand-new process called hydrogenation, which Procter & Gamble, the creator of Crisco, had perfected after years of research and development.

From the beginning, the company’s marketers talked a lot about the marvels of hydrogenation – what they called “the Crisco process” – but avoided any mention of cottonseed. There was no law at the time mandating that food companies list ingredients, although virtually all food packages provided at least enough information to answer that most fundamental of all questions: What is it?

In contrast, Crisco marketers offered only evasion and euphemism. Crisco was made from “100% shortening,” its marketing materials asserted, and “Crisco is Crisco, and nothing else.” Sometimes they gestured towards the plant kingdom: Crisco was “strictly vegetable,” “purely vegetable” or “absolutely all vegetable.” At their most specific, advertisements said it was made from “vegetable oil,” a relatively new phrase that Crisco helped to popularize.

But why go to all this trouble to avoid mentioning cottonseed oil if consumers were already knowingly buying it from other companies?

The truth was that cottonseed had a mixed reputation, and it was only getting worse by the time Crisco launched. A handful of unscrupulous companies were secretly using cheap cottonseed oil to cut costly olive oil, so some consumers thought of it as an adulterant. Others associated cottonseed oil with soap or with its emerging industrial uses in dyes, roofing tar and explosives. Still others read alarming headlines about how cottonseed meal contained a toxic compound, even though cottonseed oil itself contained none of it.

Instead of dwelling on its problematic sole ingredient, then, Crisco’s marketers kept consumer focus trained on brand reliability and the purity of modern factory food processing.

Crisco flew off the shelves. Unlike lard, Crisco had a neutral taste. Unlike butter, Crisco could last for years on the shelf. Unlike olive oil, it had a high smoking temperature for frying. At the same time, since Crisco was the only solid shortening made entirely from plants, it was prized by Jewish consumers who followed dietary restrictions forbidding the mixing of meat and dairy in a single meal.

In just five years, Americans were annually buying more than 60 million cans of Crisco, the equivalent of three cans for every family in the country. Within a generation, lard went from being a major part of American diets to an old-fashioned ingredient.

Trust the brand, not the ingredients

Today, Crisco has replaced cottonseed oil with palm, soy and canola oils. But cottonseed oil is still one of the most widely consumed edible oils in the country. It’s a routine ingredient in processed foods, and it’s commonplace in restaurant fryers.

Crisco would have never become a juggernaut without its aggressive advertising campaigns that stressed the purity and modernity of factory production and the reliability of the Crisco name. In the wake of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act – which made it illegal to adulterate or mislabel food products and boosted consumer confidence – Crisco helped convince Americans that they didn’t need to understand the ingredients in processed foods, as long as those foods came from a trusted brand.

In the decades that followed Crisco’s launch, other companies followed its lead, introducing products like Spam, Cheetos and Froot Loops with little or no reference to their ingredients.

Once ingredient labeling was mandated in the U.S. in the late 1960s, the multisyllabic ingredients in many highly processed foods may have mystified consumers. But for the most part, they kept on eating.

So if you don’t find it strange to eat foods whose ingredients you don’t know or understand, you have Crisco partly to thank.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Helen Zoe Veit is an associate professor of history at Michigan State University.