The Intoxicating History of the Canned Cocktail

Since the 1890s, the premade cocktail has flip-flopped from novelty item to kitschy commodity—but the pandemic has sales surging

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/ef/dfefaa5d-7a23-4625-8e83-c77fb0bae319/canned_cocktails-main.jpg)

When Fred Noe got married 34 years ago, his father, Booker, supplied the drinks. In addition to Jim Beam Bourbon, which Booker, Jim Beam’s grandson and sixth-generation Master Distiller, made himself, he also brought cans of Beam and cola. He appropriated a bourbon barrel to make a cooler and then put them out for guests. It was a humid day, and the supply was quickly depleted.

“They were low-proof and quite a refreshing drink. No one had ever seen them before. They were really a novelty thing for people,” says Fred, who was working in the bottling department of his family’s business at the time and became Master Distiller in 2008. He noted that premixed drinks were already a big success in Australia. “Everyone knew my dad really liked his bourbon, but he thought they’d make a good chaser. And they were quite the craze there for a little bit.”

Within eight months, the brand’s trifecta of Zzzingers (Jim Beam with cola, ginger ale and lemon-lime soda) sold close to 700,000 cases in the United States.

Today canned cocktails are a craze again. According to drinks analyst IWSR, the ready-to-drink (RTD) category grew 214 percent from 2009 to 2019. More recently, according to Nielsen, RTDs grew 40 percent from 2018 to 2019 and in late September they were up 162 percent for the past 17 weeks compared to the same weeks last year. Small craft operations and giant drink companies alike are jumping on board.

The renewed interest was sparked by small, independently minded companies that grew quickly enough to dramatically influence bigger companies. In February 2019, Anheuser-Busch bought Cutwater Spirits, a San Diego distillery that makes canned cocktails with their own liquor. Now Cutwater produces 18 varieties, including Moscow mules and mai tais. Sales are up 640 percent since they launched in 2017. In September, Beam Suntory acquired On the Rocks, a bottled line started by Dallas bartender Rocco Milano and restauranteur Patrick Halbert aiming to provide people in planes or at stadiums a quality cocktail experience.

You can chalk the popularity of these beverages up to the sine wave-patterned cycles familiar to so many realms, be it fashion, music or food. Canned cocktails have a retro appeal. Developments in packaging over the decades had an influence, as have drastic societal changes. The pandemic that’s closed bars and restaurants has compelled people to drink in their homes. Canned drinks are convenient.

Back in the 1980s, it didn’t take long before the press caught on to Booker’s tastemaker instinct.

“A LOT of soul searching went on last year at the Chicago headquarters of the James B. Beam Distilling Company,” Nicholas E. Lefferts wrote in “Adding Class to Pre-Mixed Drinks,” a December 1985 installment of “What’s New in the Liquor Business,” his New York Times column. At the time, Beam was the biggest American whiskey producer. “The question was, would putting the 190-year-old distiller's flagship brand, Jim Beam bourbon, into a canned, pre-mixed cocktail do violence to the product's image?” Lefferts added. “The answer, finally, was no, and ‘Jim Beam and Cola’ was born.”

The article does not note that there was a precedent at Beam, which sold bottled Manhattans and hot toddies in the 1960s, a Beam spokesperson confirmed. But it does explain that respectable premade cocktails were not a new concept. Lefferts alludes to Heublein’s Club Cocktails, which date back to 1892. The House of Heublein: An American Institution, published by the company, tells of Andrew Heublein who immigrated from Germany with his family to Hartford, Connecticut, and opened a fancy hotel in 1859. Andrew, the book notes, “possessed an almost uncanny ability to cater to the public’s fancies in foods, wines and line liqueurs,” a knack clearly passed on to his sons, who offered bottled cocktails—Manhattans, martinis and more—for guests to take away. They were soon christened Club Cocktails. The name, as legend has it, was an allusion to the club cars of Pullman trains. The drinks’ portability was official.

“There were bottled cocktails in the mid-19th century when bars were selling liquor retail. Regulations were much looser before Prohibition,” explains David Wondrich, drinks columnist for the Daily Beast and author of Imbibe: From Absinthe Cocktail to Whiskey Smash, a Salute in Stories and Drinks to “Professor” Jerry Thomas, Pioneer of the American Bar. “You could have a bottle of whiskey that you bought at the Occidental Bar in San Francisco. Then you get on the Union Pacific Railroad and spend a week riding across the U.S. with a supply of whiskey to nip on.”

But it was Andrew’s sons, Gilbert and Louis, who turned the Heublein brand into a national enterprise—designing labels, getting distribution, building a brand and inspiring competitors. Club Cocktails were advertised with campaigns like “A better cocktail at home than is served over any Bar in the world.”

The bottled drink boom was possible, in part, thanks to the concurrent expansion of the bottling industry. According to Barry Joseph, author of Seltzertopia: The Extraordinary Story of an Ordinary Drink, the number of bottlers grew from a little more than 100 to nearly 500 between the 1859 and the 1879 censuses. By 1889, that number grew 300 percent to nearly 1,400. The bottle was here to stay.

Joseph details the origins of The National Bottlers’ Gazette, an illustrated monthly journal founded in 1882 and run by printer William B. Keller. At that time, Joseph writes, saloons accounted for 70 percent of bottle sales. Keller aimed to unify the industry in the hopes that liquor and soft drink companies could join forces to eliminate rampant problems like bottle thievery. Bottles were meant to be cleaned, returned and refilled and typically had a lifecycle of five or six usages, but devious types found a way to exploit that. “At the same time, there was great incentive for bottlers to, essentially, steal the discarded bottles of their rivals, remove any sign of their previous owner, and then reuse them or even sell the stolen bottles at a discount to bottlers in other locations,” Joseph writes. Worse yet, the scoundrels would sell them back to the original bottlers.

But as testament to the rapid growth and, consequently, competition, rivalries between soft-drink and alcohol sectors broke out. “Call off your dogs of war, Mr. Brewer;” Keller writes, referring to the alcohol segment of the industry, “for just as sure as fate, if you and your ilk do not desist and abstain, hereafter, from slandering and libeling soda water, it will as surely lead to a trade war such as never before existed.”

With the ability to bring bottles home, drinking became a domestic pastime, and as such, ads started to target women. In 1900, a Heublein ad featured a woman instructing her butler: “Before you do another thing, James, bring me a Club Cocktail. I'm so tired [of] shopping make it a martini. I need a little Tonic and it's so much better than a drug of any kind.”

At the turn of the 20th century, cocktail-making at home wasn’t the norm quite yet.

“The actual mixing of drinks was still for the most part a mystery best left to the guild of bartenders,” Max Rudin, publisher of the Library of America, wrote in 1997 in American Heritage. “Jack London had martinis mixed in bulk by an Oakland bartender and sent up to Wolf House, his home in Sonoma's Valley of the Moon.”

Heublein continued to flourish. On the back of its bottled cocktail success, the company imported and produced their own spirits. They’re credited with bringing Smirnoff to the U.S., introducing Americans to vodka. They were able to weather Prohibition because they produced and distributed A1 Steak Sauce. After repeal, they resumed selling their liquor brands, but it wasn’t until after World War II that premixed drinks made a comeback. Heublein found a competitor in Duet, launched by National Distillers company, which flourished after the repeal of Prohibition and was purchased by Beam in the 1980s.

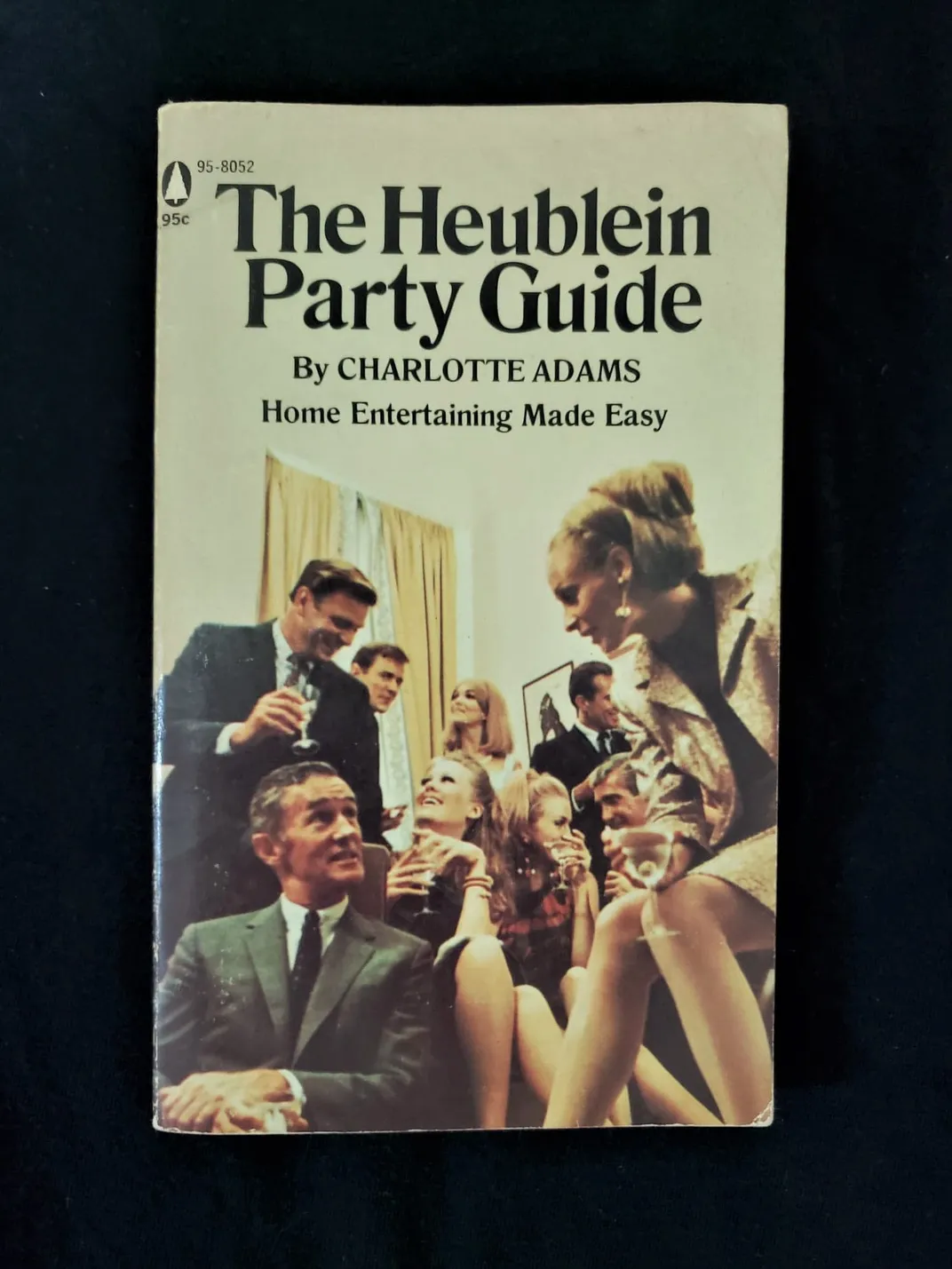

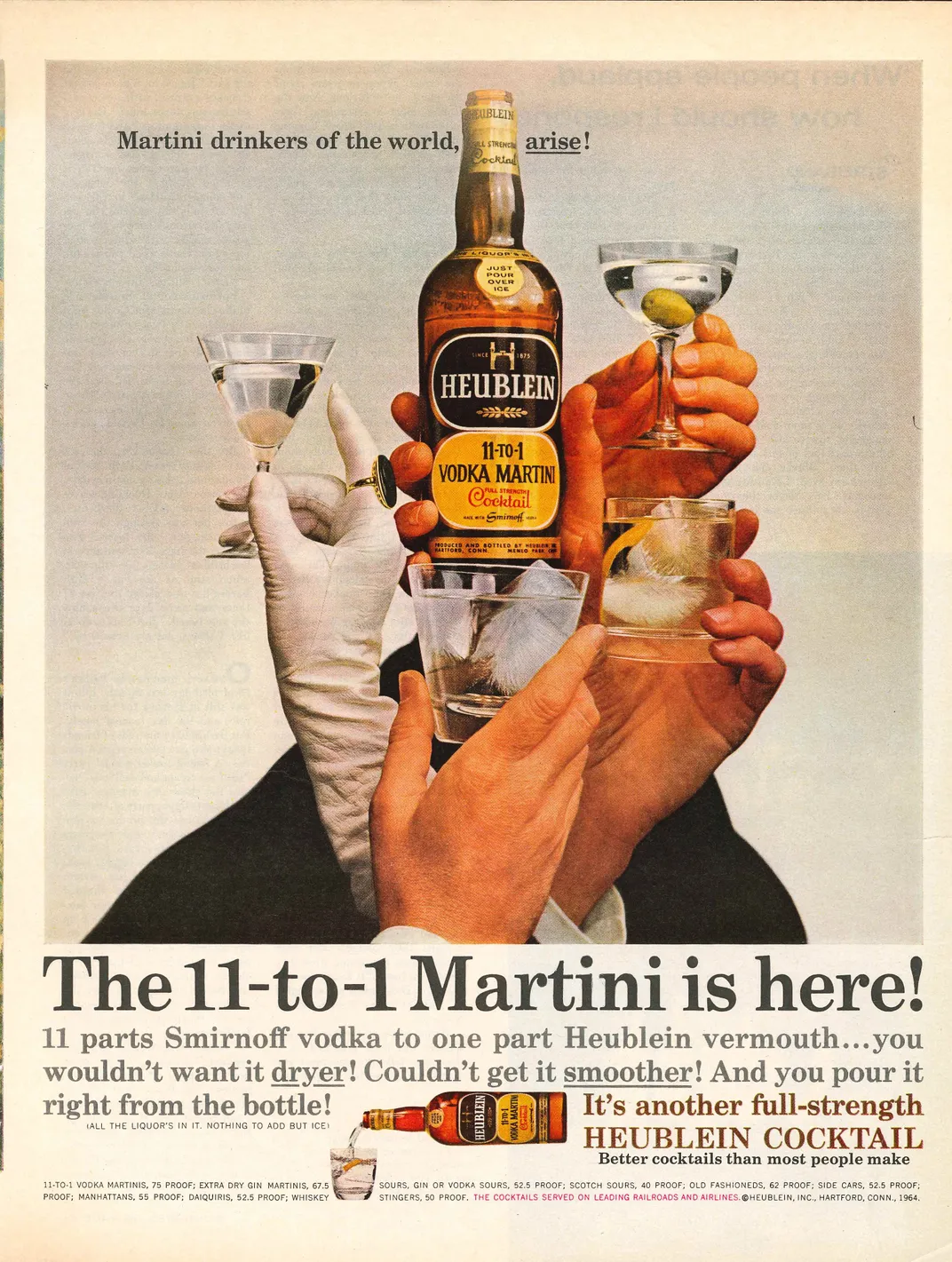

Home entertaining was back in vogue in the 1960s. (“Better cocktails than most people make,” claimed one 1964 ad for Heublein’s bottled product.) Taking notice, the company published The Heublein Party Guide: Home Entertainment Made Easy, which included cocktail recipes to promote their spirits. Premade drinks nevertheless remained popular, and soon, cans overtook bottles thanks to developments in the canning industry.

According to the Can Manufacturers Institute, canning goes back to 1795, when Napoleon commissioned a prize to anyone who could figure out how to preserve food. Enter: the tin-plated can. The first patent for tin-plated steel cans was awarded in 1810 in England. In 1935, Krueger’s Brewing Company, in New Jersey, became the first producer to put an alcoholic beverage in a can. But the tinplate was a problem.

“The human senses are highly sensitive to iron pickup. Even a tiny exposure to metal and you’ll taste it,” explains Dan Abramowicz, chief technology officer at Crown Holdings, Inc., a metal packaging company founded by the inventor of the still-ubiquitous crown bottlecap. “The coatings weren’t great at the time, so beer would have a bit of an aftertaste,” he says. But coatings improved in the 1950s, and manufacturing techniques became more efficient, giving rise to the 3-piece can, made by rolling a flat sheet of metal into a cylinder, welding it shut (originally they were soldered), and seaming on the top and bottom.

Everything changed in 1959 when Molson Coors Brewing Company introduced aluminum cans and developed a two-piece manufacturing method. The innovation’s success was two-fold: it didn’t adulterate the flavor of their light lagers and it was recyclable. Bill Coors, longtime CEO of his family’s brewery, was known for his commitment to environmental causes. To that end, he developed a sustainable container.

“Roughly 80 percent of all the metal ever made (steel or aluminum) is still in use today,” Abramowicz explains. “It takes a lot of energy—and therefore money—to make the metal the first time from ore and other materials. It takes only a fraction of that energy (5 percent) to convert recycled metal into new metal. That’s why recycled metal is so valuable.”

Through the 1970s, Club Cocktails saw competitors like Party Tyme and Duet (so-named because it contained the equivalent of two drinks), all sold in eight-ounce cans. By 1986, acquisitions and restructurings involving R.J. Reynolds Tobacco and Nabisco shook up the Heublein company. Its alcohol brands, including Club Cocktails, were sold to Grand Metropolitan, which would later become part of Diageo, one of the biggest drinks companies today with brands such as Johnnie Walker, Guinness, Crown Royal and more. According to documents at the Diageo Archive in Scotland, annual sales of Club Cocktails hit 1.5 million cases in the U.S. at its height in the mid-to-late 1950s. The document, which is estimated to have been drawn up in the late 1990s, shows sales of Club Cocktails at the time totaling 470 9-liter cases. The brand was available in 26 flavors in four sizes of cans and glass bottles. After Prohibition, Club Cocktails splintered with the launch of the bottled Heublein Cocktails line, comprised of basic drink recipes like whiskey sours and daiquiris. Dubbed “adventurous cocktails” and bottled at “full strength,” they were known for their celebrity-studded ad campaign in the 1950s and 60s, featuring the likes of actors Jack Palance and Peter Lawford and singers Robert and Carol Goulet, and the tagline “15 kinds, better than most people make.” At their height in the late 1950s, annual sales reached 700,000 cases. In an email, the Diageo archivist wrote, “Not surprisingly, the document goes on to say that both had lost volume in recent times as a result of category innovation and growth in RTD brands, as well as wine and malt-based coolers.”

Both Heublein and Club Cocktails were outlasted by Beam’s Zzzingers, which were discontinued in 2007.

It’s not completely clear why canned drinks fell out of favor in the 1990s. It was about the time that cosmos and flavored martinis stole the spotlight, which could have played a role. Fred Noe attributes it to price. It was cheaper to buy a bottle of bourbon and cola. Canned cocktails, it’s important to note, are taxed as spirits, even though that only accounts for a proportion of the liquid. That, in turn, explains the rise of malt beverages like Zima. The tax law on spirits still holds today and accounts for the stratospheric growth of alternatives like hard seltzers, such as White Claw.

With the revived interest in canned cocktails, newer brands put bartenders front and center, thus emphasizing the artisanal element of the product. In August, Julie Reiner and Tom Macy, two owners of Brooklyn’s award-winning Clover Club, unveiled Social Hour Cocktails, a line made with spirits from the celebrated New York Distilling Company. LiveWire was launched in March by Aaron Polsky, a longtime bartender at some of New York and LA’s most popular cocktail bars. He tapped noted bartenders around the U.S. to provide recipes. (His own concoction, Heartbreaker, is a mix of vodka, grapefruit, jasmine, kumquat and ginger.) Polsky was inspired, he said, by the record label model: you can get a cocktail from a bartender at a bar (the live show) or you can enjoy it at home (the recording).

“It’s how you scale your art,” Polsky says. But he notes how much precision engineering is involved in formulation. “If I make you a drink at the bar, I have full control over the temperature, dilution, presentation. When you’re drinking LiveWire, I have no control. I balanced the cocktails in such a way that they need nothing. It’ll taste good at a variety of temperatures. If you have a can, it should not require anything other than being cold.”

The Heubleins would be proud.