A New Generation of Autonomous Vessels Is Looking to Catch Illegal Fishers

A design challenge has tech companies racing to build a robot that can police illegal fishing in marine protected areas

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/34/6c/346c386b-b389-4bbc-8d4f-3d12a58042f9/open_ocean_robotics.jpg)

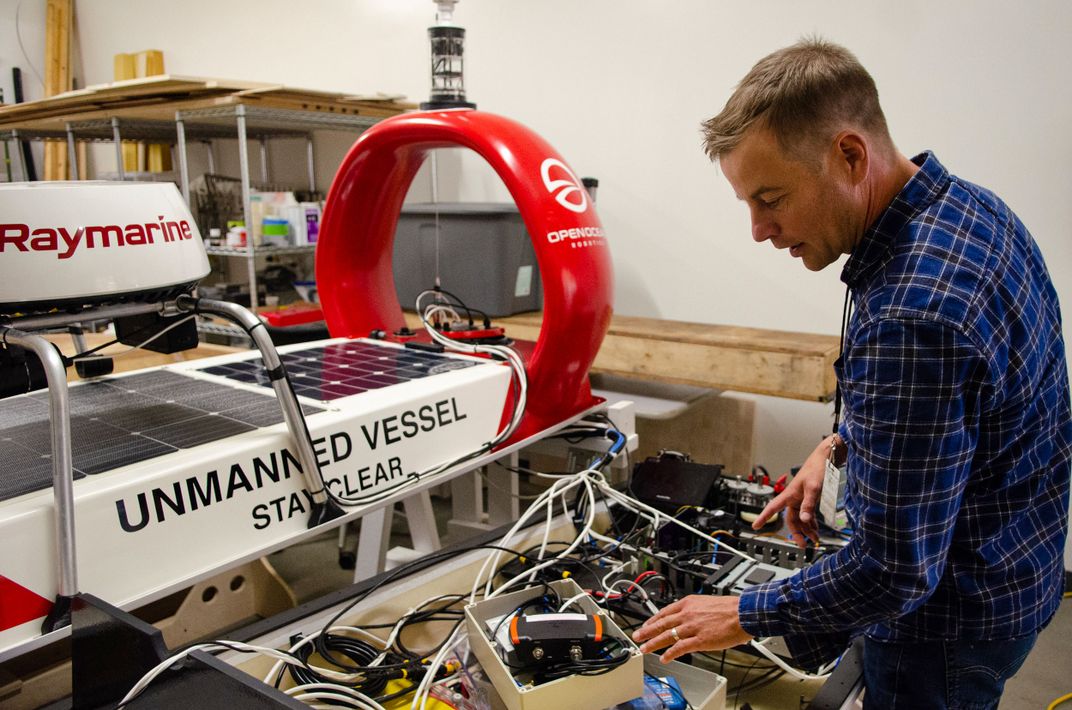

The first time engineers from Open Ocean Robotics pushed Scooby, a three-meter robotic boat, onto a lake near their office in Victoria, British Columbia, the small craft drove straight into the bushes. Clearly, the team had more work to do on the vessel’s autopilot.

Since that early mission last year, the start-up has won innovation awards, secured seed funding, and “spent tons of time on the water” ironing out the kinks in their autonomous vessels, says Julie Angus, the company’s CEO and cofounder. The 12-person team is now up against Connecticut-based tech company ThayerMahan and Marine Advanced Robotics from Silicon Valley in a cutting-edge design challenge to build a robot that can police illegal fishing in marine protected areas (MPAs). Scooby's successor (named after another character) completed the first stage in the multiyear project: a three-day field demonstration using surveillance technology to track boats, detect fishing activity, and collect evidence.

To protect marine wildlife and ecosystems and sustain fisheries, the United Nations, governments, and NGOs are pushing for more and bigger MPAs. But without a clear means of enforcing the regulations that govern them, these areas often draw criticism for being little more than paper parks. In partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), these three robotics companies are racing to prove that uncrewed vessels are up to the task.

Originally, the trial was planned for the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary off Santa Barbara, California, but pandemic restrictions meant the participants tested their prototypes separately from around North America and presented the results to the judges remotely. Justin Manley, founder of Just Innovation, the Massachusetts-based marine robotics consultancy coordinating the project, says the upside of the disparate testing is that it let them see how effectively the robots detected different types of fishing boats.

For the 72-hour trial, Daphne followed a route programmed by Open Ocean Robotics engineers. The craft switched between patrolling around Danger Reefs, a rockfish conservation area off Vancouver Island’s east coast, mapping the seafloor, and loitering in a safe anchorage. Back in a control room at the company’s office, team members had a multi-sensor view of the ocean environment. An array of screens displayed maps crisscrossed by Daphne’s path, red-on-black radar imagery, a high definition video stream, and other real-time data, all transmitted by cellular network. As two hired salmon trollers mimicked fishing in the protected area, a remote operator moved Daphne closer so the 360-degree and thermal cameras could capture images of the trollers’ names and fishing lines.

Daphne's surveillance systems collect different types of evidence. With radar, Open Ocean Robotics can identify, locate, and track targets. Angus says operators can infer suspicious activity if a ship is loitering or moving back and forth in a protected area, rather than transiting through. Comparing radar with automated information system (AIS) ship-tracking data is also useful for spotting suspect targets—“if a boat is fishing illegally, quite likely they’re going to turn their AIS off,” Angus says. Daphne also tows a hydrophone to collect corroborating audio, such as the whine of a hydraulic winch hoisting a fishing net.

For years, robots have worked underwater and on the sea’s surface to complete tasks too dangerous, expensive, or dull for humans. Now, they’re tackling more complex problems that require artificial intelligence, such as autonomously patrolling for submarines for the Australian Department of Defence. Civilian work, like policing MPAs, draws on similar technology.

The real question,” says Manley, “is can we collect enough information that law enforcement would act?” To do so, Daphne and its ilk will have to identify fishing activity with a high degree of accuracy.

But this is an untested frontier. In the United States, no court case has relied entirely on information gathered by robots. In California, a vessel having fishing gear in the water in off-limits areas is grounds enough to prosecute. The design challenge judges—California state attorneys, and conservation and enforcement experts from NOAA and CDFW—are now gauging whether the evidence collected by the uncrewed vessels could hold up in court.

For the best robot design, there’s a staggering amount of work on the horizon. The United States has nearly 1,000 MPAs covering 26 percent of its territorial waters. Some, such as the 1,508,870-square kilometer Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawai‘i, are completely closed to fishing, while others have closures based on season, gear, or species.

Globally, there is a wide disparity in MPA enforcement capability—a gulf that is unlikely to be filled by robots like Daphne, given their substantial upfront costs. One small Open Ocean Robotics vessel costs several hundred thousand dollars, depending on the sensors with which it is equipped. But, Angus says, that price is one-tenth of the cost of a ship and crew time. “And you have the ability to deploy it 24/7,” she says.

Lekelia Jenkins, a marine sustainability scientist at Arizona State University, says some developing countries do not have the resources for patrol boats and personnel. Even if these governments can obtain ocean robots, she adds, they “often don’t have the scientific manpower to analyze all that data.” In many cases, investing in healthcare, education, and overcoming poverty take precedence over fisheries enforcement.

Jenkins also says there’s a real trade-off to robots replacing people on the water. When local residents work as guardians or in ecotourism in protected areas, “people can point back and go, Here’s how I’ve benefitted financially from the MPA.”

Autonomous vessels reduce the need for people, Jenkins says, and robotics companies are more likely to bring in expertise than invest in training local residents to build specialized infrastructure or operate vessels.

But long before docks are built to launch oceangoing bots, the participants need to show their technology is up to the task. The design challenge’s next stage will test the vessels on longer, more remote deployments. In those conditions, autonomous vessels will need to use AI to identify objects of interest then notify operators by satellite—capabilities that Open Ocean Robotics is currently developing.

Todd Jacobs, NOAA’s chief technology officer for unmanned systems, says developing AI is crucial to the use of uncrewed vessels. “There’s not enough data storage in the world to [keep] high definition images of the monotony of empty water, which is 90 or 98 percent what you’re going to see,” he says.

Agency wide, NOAA is investing US $12.7-million to increase its use of autonomous and remotely operated vessels, airplanes, and drones for science and enforcement. Over time, Jacobs says, data collected by uncrewed vessels will help NOAA discern patterns of illegal fishing activity, so the agency can focus enforcement efforts.

The future of robot police is nearly here—and governments are rushing to meet it.

Open Ocean Robotics’ technology has come a long way since that first day on the lake. On the ocean near Victoria this fall, Daphne surprised the engineers by moving off its programmed track to surf the wake of their research boat—on its own. If Open Ocean Robotics progresses to the next round, Daphne may soon be catching waves off California or Hawai‘i.

This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

Related stories from Hakai Magazine:

In Covid's Shadow, Illegal Fishing Flourishes

How Do You Surveil One of the Largest Marine Protected Areas on Earth?