The Scientist Behind Some of Our Favorite Junk Foods

William A. Mitchell invented Cool Whip, Pop Rocks, Tang and other 20th-century treats

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/f1/7df1da45-d7fd-4114-b753-7d939372b97c/cool_whip.jpg)

Hong Kong is one of the world’s greatest food cities, yet every so often I find myself traveling across town searching for a delicacy that’s hard to find amidst the dim sum shops and exquisite French restaurants.

Cool Whip.

Say what you will, but there’s nothing like a bowl of cherry Jell-O topped with a fluffy raft of faux whipped cream on a hot night. And both foodstuffs can be credited to the same inventor: William A. Mitchell. In honor of National Junk Food Day on July 21, we’re taking a look at Mitchell’s work, which falls squarely into America’s midcentury love affair with convenience foods.

Mitchell was a Midwestern farm boy, born in rural Minnesota in 1911. As a teenager, he ran the sugar crystallization tanks for the American Sugar Beet company on the overnight shift, sleeping two hours before heading to high school. He worked as a carpenter to earn his tuition to Cotner College in Lincoln, Nebraska, and hopped a train to get there. He went on to get a graduate degree in chemistry at the University of Nebraska. As a young chemist working at the Agricultural Experiment Station in Lincoln, he was badly burned in a lab explosion. After recovering, he went to work at General Foods at the start of World War II. There, he developed a substitute for tapioca, which was in short supply due to conflicts in the Pacific. The combination of starches and gelatin kept hungry soldiers satisfied (they nicknamed the substance “Mitchell’s mud,” apparently in appreciation).

In 1957, Mitchell came out with a powdered fruit-flavored vitamin-enhanced drink mix. The glowing orange concoction was called Tang Flavor Crystals. In 1962, NASA began sending Tang into space to disguise the metallic taste of the water onboard the spaceship (dehydrated orange juice was too grainy), giving the powder an indestructible aura of Space Age chic (though John Glenn allegedly disliked it, and years later Buzz Aldrin proclaimed “Tang sucks.”).

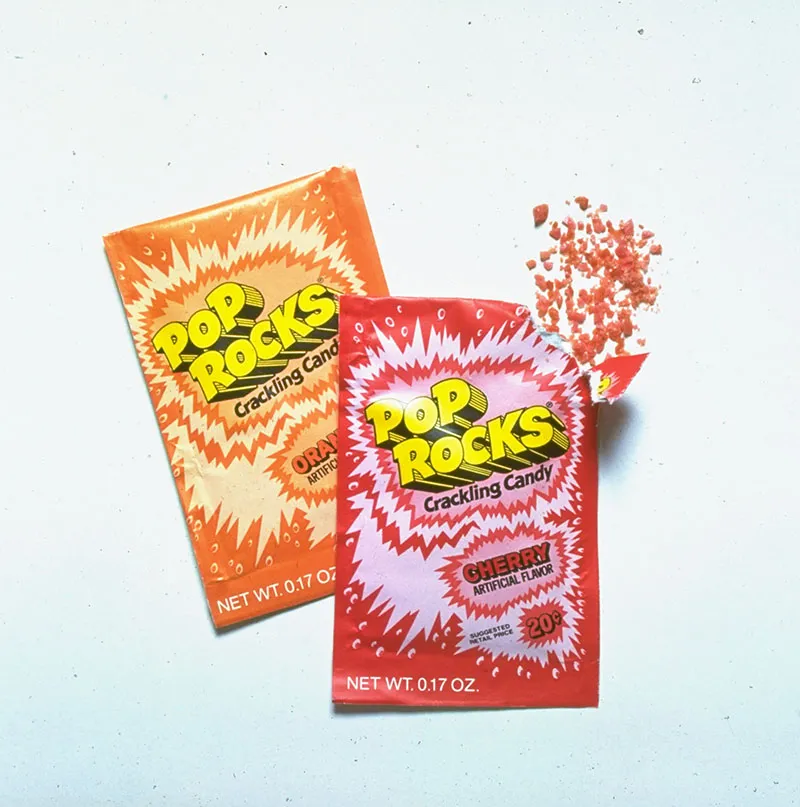

In 1956, Mitchell’s attempt to create instantly self-carbonating soda resulted instead in the candy now known as Pop Rocks, which was patented in 1961 and hit the market in the mid-1970s. Bubbles of carbon dioxide trapped in the candy release in your mouth with little electric zings—delightful, if a bit alarming at first. It spawned related treats like Increda Bubble popping gum, subject of an amazingly retro ad. But the new sensation also led quickly to wild urban legends. If you grew up in the '80s and '90s, you might remember the alleged tragedy of Little Mikey, the boy from the Life cereal commercials, who it was rumored met his untimely end when his stomach exploded from a combination of Pop Rocks and Coke. ("MythBusters" busted that one.)

General Foods took out ads in 45 major publications and wrote 50,000 letters to school principals explaining that Pop Rocks really, definitely can’t kill you. Mitchell even went on a pro-Pop Rocks publicity tour. But the candy was eventually pulled from the market. It was later bought by another company and reintroduced.

In 1967, Mitchell patented a powdered gelatin dessert that could be set with cold water, which paved the way for quick-set Jell-O. No longer would Americans have to wait two to four hours for their lime Jell-O rings with crushed pineapple. The same year, Mitchell introduced the faux whipped cream called Cool Whip, which quickly became the largest and most profitable product line in its division. The original recipe was totally dairy-free, though it now contains a small amount of milk product. Kraft Heinz, Cool Whip’s current owner, still sells 200 million tubs of the stuff a year (at least 5 of which are to me).

Mitchell received some 70 patents over his long career. He retired in 1976 and died in 2004, at the age of 92. His daughter Cheryl, one of his seven children, also became a food scientist. But her innovations are a far cry from her father’s junk food delights—she’s a pioneer of vegan “milk,” creating dairy-like tastes from peanuts, almonds and rice.

Not all Mitchell’s inventions were successful. Dacopa, a coffee substitute made from roasted dahlia tubers, never made the big time. His 1969 patent for “dessert-on-the-stick,” a starch-based dessert powder so thick it could be made into popsicle-like treats at room temperature, was not a hit (though I for one would love to try it). His patented carbonated ice never became a thing (again, why not?).

Mitchell was a “true inventor,” wrote Marv Rudolph, a fellow General Foods scientist, in his book Pop Rocks: The Inside Story of America's Revolutionary Candy, “a person who looks at problems differently and can find elegant, sometimes simple solutions that no one else considered.”

“If you generate enough intellectual property in the laboratory to issue a patent, on the average, every ten months of your career, you have joined a very exclusive club,” Rudolph wrote.

Though some of Mitchell’s inventions are still wildly popular, his style of lab-made, science-forward foods has fallen out of favor. In Mitchell’s postwar heyday, consumers gobbled up modern convenience foods, many of them developed during the war as shelf-stable soldiers’ rations. Today, with organic, local and slow food trends, many consumers give the side-eye to foods made with ingredients like “pregelatinized modified food starch” and “polysorbate 60.”

And no, Cool Whip is not the healthiest. But sometimes you just want something sweet and familiar that won’t melt all over your groceries on the long hot walk home.

So celebrate National Junk Food Day with some of Mitchell’s greatest hits. You can even combine them, as does this recipe for the retro Southern classic, Tang Pie.

Tang Pie

1 prebaked pie shell

½ cup Tang powder

1 tub of Cool Whip

8 oz sour cream

14 oz sweetened condensed milk

Mix ingredients and pour them into a pie shell. Refrigerate until cold. If you sprinkle the top with Pop Rocks that wouldn’t be a bad thing. You definitely won’t explode.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)