A Bizarre “Swimming with Tuna” Attraction Puts Australia’s Controversial Aquaculture in the Spotlight

Is this an opportunity for conservation education, or another example of the government bending to Big Tuna?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/df/a5df5642-982f-4fb3-99f1-3956540ef504/header-swim-with-tuna.jpg)

This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

A handful of sardines is tossed into the water. And another. The little fish vanish as other, much bigger fish rocket up from the murky black depths to gobble them. The tuna slice through the water with the precision and speed befitting their nickname, “Ferraris of the ocean.”

A boy pops his head up from the water. “Is this real life?” he screams from the floating fish pen. It’s a weekday in Port Lincoln, Australia, and bluefin tuna purveyors Yasmin Stehr and Michael Dyer are playing hooky with family and friends. They’re testing out their latest commercial venture, Oceanic Victor, which focuses on the coveted bluefin—not as food, but as entertainment.

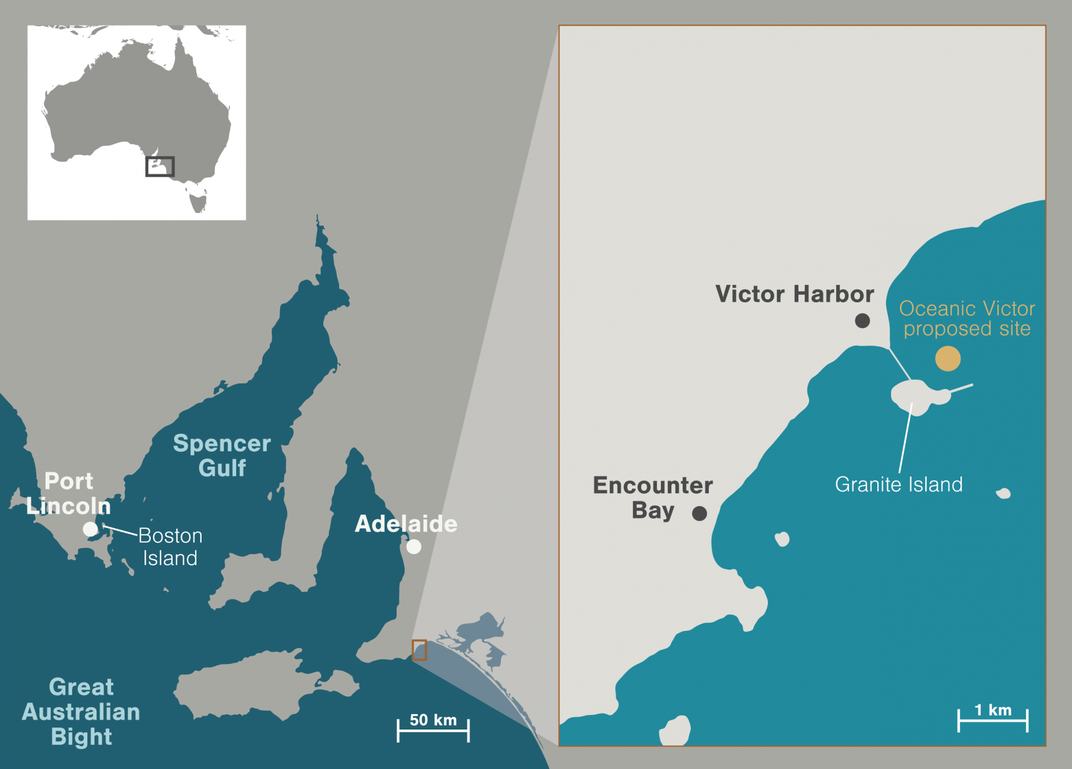

Behind the boy’s snorkel mask is a look of sheer glee. It’s the kind of look Stehr and Dyer hope to elicit from many more people when they launch their swim-with-tuna operation in Victor Harbor, a small coastal town and tourist hub over 700 kilometers away.

First, however, they have to overcome the protestors.

Within a few months of Stehr and Dyer applying for permits, there was public uproar in Victor Harbor. In December 2015, the same month Oceanic Victor was scheduled to open, 83 objections were lodged against the proposal, citing concerns that the pen—identical to the kind used in tuna aquaculture—would cause danger to other species and environmental degradation. Local businesses hung protest fliers in their windows, opponents circulated a petition, and the lifeguards erected a massive banner across their watchtower. By mid-February, protesters had filed four separate appeals against Oceanic Victor, stalling its launch.

“We were blindsided,” says Stehr, later adding, “We thought that we were the good guys coming in with an educational facility.”

Instead, the battle over the attraction has exposed a general rift about the much-lauded, and valuable, industry it symbolizes—tuna aquaculture in Australia—sparking accusations of governmental kowtowing to the tuna ranchers and doubts about the fishery’s true level of sustainability.

**********

Before Stehr and Dyer took over the floating tuna tank and made plans to relocate it, a similar operation ran without objection in Port Lincoln for years. The polarity in public opinion boils down to this: The people of Port Lincoln were naturally more open to the attraction because it’s emblematic of their livelihoods. As many as 4,000 of the 14,900 or so residents work in the fishing industry.

Yet Port Lincoln, a winding 8-hour drive from Victor Harbor, isn’t exactly what springs to mind when you say “fishing town.” Beyond the city’s agricultural outskirts, wealth subtly glimmers. Evenly spaced palms line the road to the Lincoln Cove Marina, home to the largest fishing fleet in the southern hemisphere, an indoor pool, and a four-star hotel. Just down the street, glossy SUVs sit in front of new condominiums on roads with names like “Laguna Drive.” And the archetype grizzled fisherman is nowhere to be found: the “seafood capital of Australia” is reported to have the most millionaires per capita in the country.

While the region is also known for shellfish such as abalone and mussels, and the oyster industry alone is estimated to be worth $22 million, it’s most famous for southern bluefin tuna, Port Lincoln’s pearl. A single tuna—later transformed into as many as 10,000 pieces of sushi—can sell for $2,500 at Tokyo’s famous Tsukiji Market. (In 2013, one fish that was considered auspicious reportedly sold for $1.76 million.)

At the airport, a life-size tuna greets arrivals, and during the annual Tunarama Festival, spectators watch the “world famous” tuna toss competition. Documentaries such as Tuna Cowboys and Tuna Wranglers have profiled the wealthy anglers who call Port Lincoln home.

Once on the brink of bankruptcy, the community is reveling in its good fortune. The southern bluefin tuna, a highly migratory fish found in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans, has been heavily targeted since the 1950s. Just 20 years ago, both the species and the fishery were staring down extinction. Australian fishermen had begun to reel in as little as 5,000 tonnes annually—20,000 tonnes less than just three decades earlier. As little as 3 percent of the original southern bluefin population remained.

In 1993, the three nations responsible for 80 percent of the catch—Australia, Japan and New Zealand—rallied. They agreed to a yearly quota system, managed by the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT), in an effort to curb the decline. The restrictions inspired creativity: how, the Australian fishermen wondered, to produce more meat with fewer fish?

The solution was floating feedlots. Each year, the fish travel from their spawning grounds off northwest Australia in the Indian Ocean south and then east to the reefs of the Great Australian Bight to feed, making them an easy target. Between December and March, fishermen capture around 5,500 tonnes of wild juvenile tuna—roughly 367,000 fish—using a purse seine method, which involves encircling a school with a weighted fishing net and then cinching it closed at the bottom, like an underwater drawstring bag.

Over two weeks, the fish are towed in the net behind the boat at a glacial pace to Spencer Gulf, near Port Lincoln, before being transferred to “ranches.” For the next three to six months, the tuna live in large pens—each containing between 2,200 and 3,500 fish—where they’re plumped up on a steady diet of high-fat sardines. Once ready for market, the tuna are shipped by freezer boats or live airfreight to their final destination, usually Japan. A single pen full of tuna can net upward of $2 million.

While the method of aquaculture has since been adopted along Mexico and in the Mediterranean Sea to raise northern bluefin and Atlantic bluefin, Port Lincoln remains the only place in the world where southern bluefin are ranched. It’s also the only place that doesn’t catch southern bluefin by longlining, a controversial commercial fishing method that uses a long hooked line to trawl waters and often kills other species in the process.

Today, tuna aquaculture is one of Australia’s fastest growing sectors; about 15 tuna ranching companies operate in South Australia, bringing in between $114 and $227 million annually. (Compare that to Canada, where the entire country’s commercial tuna industry is only worth $17 million.) Pioneers of the ranching method became rich and put Port Lincoln on the map as a leader in sustainable seafood production.

“The future is not the Internet; it’s aquaculture,” local fishing baron Hagen Stehr, Yasmin Stehr’s father, told Forbes in 2006.

The CCSBT claims the quota system is working. Evidence from aerial surveys, tagging and data projections suggests that tuna have rebounded to about 9 percent of their original spawning biomass, up from the low of 3 percent. By 2035, CCSBT predicts, the wild stock will have returned to 20 percent of its original spawning biomass. That estimate may seem underwhelming, but it’s enough to make the commission reassess its policies.

“We’re actually getting increases in quotas because the population is so robust,” says Kirsten Rough, a research scientist with the Australian Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association. Just last December, Port Lincoln’s fishing industry was awarded sustainability accreditation by the NGO Friend of the Sea.

However, while tuna aquaculture is touted as an ecologically friendly way to meet the insatiable demands of the Japanese sashimi market, there’s evidence that tuna are actually floundering.

Fish are tricky to count, which makes determining their population an inexact science. More conservative estimates put the current percent of spawning biomass closer to five percent. The CCBST’s efforts to conserve the species are good, but according to other monitoring bodies, they’re far from good enough. While Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act only classifies the fish as “conservation dependent,” they remain on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s critically endangered list.

As the world’s population grows, aquaculture has become increasingly important to food security. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimated in 2010 that an additional 27 million tonnes of farmed fish would be needed to maintain the present level of global fish consumption per capita in 2030. Today, aquaculture provides half of all fish consumed by people globally.

But while aquaculture typically has a lower environmental footprint than traditional commercial fishing methods, tuna is an exception. The species’ feed conversion ratio is exceptionally low compared to other farmed fish; a tuna needs to chow down on as much as six times more food than a salmon does. Australia catches more than 38,000 tonnes of sardines every year just to satiate the demands of Port Lincoln’s fisheries, making sardines the most heavily fished species in the country.

Tuna are also notoriously difficult to breed. The young are especially fragile and sensitive to water temperature, currents, and changes in their environment. The ranchers’ reliance on juvenile wild stock means that tuna are possibly being caught before they can reproduce. And although the quota system was developed to ensure the long-term survival of the species, it’s managed by the same industry that profits from it. Tuna ranch operators are rarely subject to independent third-party assessments. The result may be systemic overfishing and false counting.

When compared to the fishing practices that nearly decimated the tuna population, it’s undeniable that aquaculture is a necessary alternative. Industry spokespeople are justified in boasting about how they’ve reduced by-catch by eliminating longlining, yet they overlook an important point—pens take a toll on the environment, too. Ranches collectively release 1,946 tonnes of nitrogen every year—a common stressor in marine ecosystems, known to promote algal growth and smother marine life—making them the largest industrial contributor of pollution to the Spencer Gulf.

For critics of Oceanic Victor and the industry at large, such as Nisa Schebella, a protestor from Victor Harbor, putting people into a pen to swim with the species is overexploiting an already beleaguered species. It’s one thing to keep highly migratory animals in a pen for food—it’s another to do it solely for frivolity. “The more I research, the more I’m bamboozled by the whole fishing industry at large and its dismissal of tuna’s critically endangered status,” she says.

**********

On a blazing February morning in Victor Harbor, hundreds of people have gathered on the lawn in front of the local yacht club to rally against Oceanic Victor. Mark Parnell, the leader of the South Australia Greens party, hollers into a loudspeaker: “What the proponents will tell you is, ‘Oh you silly people, you don’t understand anything.’ I think you have every right to be suspicious and every right to be concerned.”

United, the protesters stream into the water of Encounter Bay toward Granite Island, with their surfboards, catamarans and float toys, forming a circle in view of the proposed site of Oceanic Victor.

The proposal Oceanic Victor presented in 2015 was an easy sell for the Victor Harbor Council. Worth $2.4 billion, tourism in South Australia is even bigger business than tuna, but Victor Harbor has been struggling to attract its share of attention. So council fast-tracked the application and Oceanic Victor received its aquaculture license and approvals from both the Victor Harbor Council and the state government to lease a section of water in the Encounter Bay Marine Park, a protected area.

“They went through the process and got a tick box for an aquaculture license—even though it’s in … a habitat protection zone. So what’s to stop it from happening in the future?” says one conservationist, who asked not to be named. “When [the tuna industry] says ‘jump,’ the government jumps.”

The pedigrees of Oceanic Victor’s owners add to the suspicion. Yasmin Stehr’s father, Hagen, made millions with Clean Seas, his fishing company based in Port Lincoln. Her partner, Dyer, is the operations manager of Tony’s Tuna International, another industry heavyweight, and Oceanic Victor is co-owned by “Tony” himself, Tony Santic.

Although Oceanic Victor’s license prohibits them from farming fish (the fish will live out the entirety of their lives in the pen) critics believe that moving the pontoon into Encounter Bay could have untold ripple effects. Although no bird or mammal deaths, entanglements or even shark interactions—the main concern of this particular group of protesters—were reported during the four years that the attraction was located in Port Lincoln under its former ownership, Encounter Bay is a different ecosystem.

Every year, endangered migratory southern right whales use the bay as a nursery. Any increase to predators means that whales may pass by, putting both their population and the town’s main tourism draw at risk. While experts think it’s unlikely that sharks from outside the local area will be attracted to the pen, the same can’t be said of long-nosed fur seals, which have a taste for tuna meat. If attracted to the area, the seals are also likely to hunt and decimate the vulnerable population of little penguins in the area.

While the stocking density of the pen will be low, with only 60 fish, compared to thousands kept in commercial pens, Victor Harbor’s Encounter Bay is shallow. Oceanic Victor went through what Stehr says was a “vigorous and exhaustive application process”—including public consultations and government environmental evaluations—yet no assessments were conducted regarding the area’s water flow or the potential effects of nitrogen discharge.

The protesters’ fixation on sharks has helped keep the opposition a front-page news item, but is detracting from what could be their strongest argument—in an era when SeaWorld’s profits are crashing and tourists are increasingly questioning whether animals should be kept in pens for entertainment, swimming with tuna is an antiquated approach to how we interact with wildlife.

“The political landscape with respect to keeping animals in captivity is changing rapidly,” Tony Bertram, a member of the Kangaroo Island/Victor Harbor Dolphin Watch, wrote in an appeal letter to the state government. “Is this really something the people of Victor Harbor wish to link themselves to?”

If approved, Oceanic Victor also arguably has the potential for good. As marine scientist Kirsten Rough points out, allowing children to interact with wildlife could play a role in conserving the threatened species. “I gained my love and respect for the sea and my desire to learn more about ecosystems and the importance of looking after what we have through hands-on experience,” Rough says of her own childhood growing up seaside. Oceanic Victor, she argues, will spark that same interest in future generations.

Researchers at Kindai University in Japan have demonstrated that industry can be a powerful driver of conservation, too. With the financial support of the domestic fishing industry, they’ve recently developed the technology to breed Pacific bluefin tuna, closing the lifecycle. In due time, the technology will likely be adopted in the Port Lincoln area, reducing the industry’s reliance on wild-caught fish—and potentially affecting the entire industry’s balance of supply, demand and valuation.

To the average bystander, Oceanic Victor may seem as bizarre as it is controversial. Sure, we swim with dolphins, sharks, rays and a whole host of other marine creatures—but tuna? Dip your head in the water and watch an 80-kilogram fish whip toward you at highway speeds and you’ll quickly understand the appealing mix of terror and exhilaration. Australia’s tuna industry may be poised to change at the same breakneck speed, but one thing will always hold true: for as long as South Australia is located by the sea, the livelihood of its people will depend on fishing and tourism. Balancing the demand for one species with the negative ripple effects of that demand will always be a challenge. Critics and proponents will be waiting for the final ruling on Oceanic Victor’s fate in Victor Harbor later this month to see which way, this time, the tuna scales will tip.

Related Stories from Hakai Magazine:

Editor's Note, June 1, 2021: The story has been updated to correct a statement that was misattributed to researcher Kate Barclay.