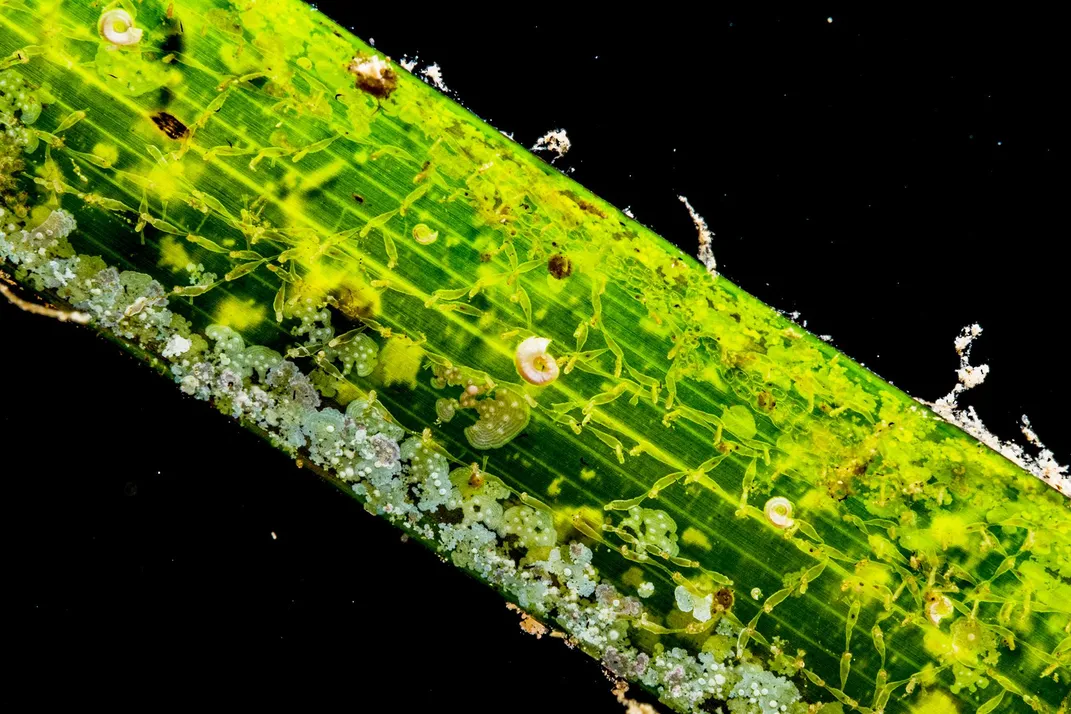

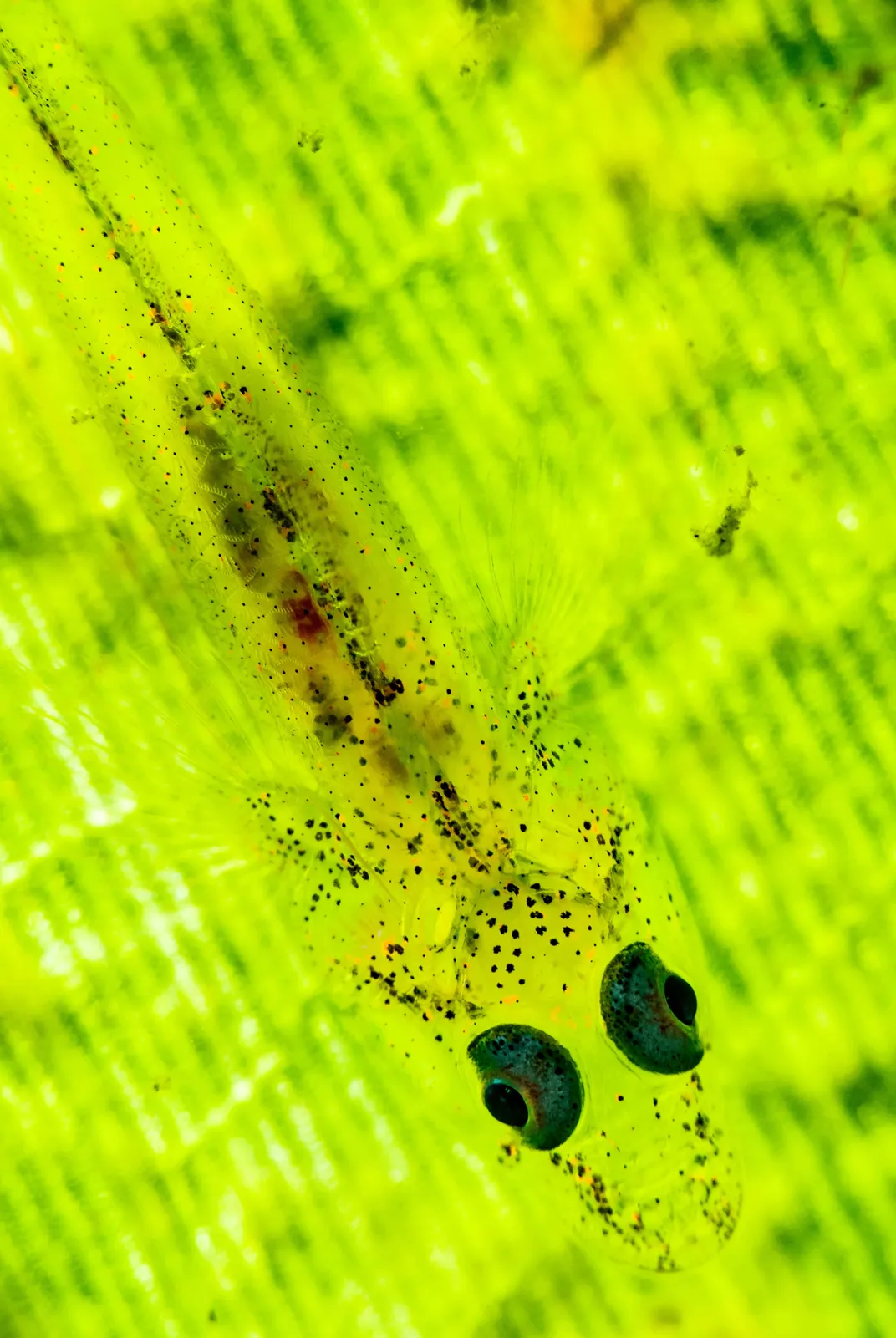

Bright sunlight filters down through the clear Mediterranean waters off the coast of Spain, illuminating a lush meadow just below the surface. Blades of strikingly green grass undulate in the currents. Painted comber fish dart among clumps of leaves, and technicolor nudibranchs crawl over mounds. Porcelain crabs scuttle by tiny starfish clinging to the blades. A four-foot-tall fan mussel has planted itself on a rock outcropping. A sea turtle glides by.

This rich underwater landscape has been shaped by its humble covering, Posidonia oceanica. Commonly known as Neptune grass, it is one of about 70 species of seagrasses that have spread, over millions of years, across the globe’s coastal shallows, embracing and buffering continental shelves from Greenland to New Guinea. Seagrasses provide habitat for fish, sea horses, crustaceans and others; food for sea turtles, waterfowl and marine mammals; and nurseries for an astounding 20 percent of the largest fisheries on the planet.

“Seagrasses are the forgotten ecosystem,” Ronald Jumeau, a United Nations representative from the Republic of Seychelles, writes in a 2020 U.N. report. “Swaying gently beneath the surface of the ocean, seagrasses are too often out of sight and out of mind, overshadowed by colorful coral reefs and mighty mangroves.” But, he says, they “are among the most productive natural habitats on land or sea.”

Emmett Duffy, director of the Smithsonian’s Tennenbaum Marine Observatories Network, shares that view of seagrasses as underappreciated but essential: “They’re like the Serengeti grasslands of Africa—but hardly anybody knows about them.”

Yet this invisible ecosystem, once you do see it, has a primal if uncanny draw, at once alien and familiar, a remembered dream of a submerged meadow. This may be because, unlike seaweeds (which are algae, not plants) and corals, seagrasses are terrestrial immigrants. When the largest dinosaurs were in their heyday, these grasses drifted from dry land into the sea.

They have changed little since then. Like land grasses, they grow leaves, roots, rhizomes, veins and flowers. Their modest adaptations to the marine environment include aquatic pollination, neutrally buoyant seeds that can drift with the current before settling, and leaves that manage saltwater. These adaptations have led seagrasses to cover some 116,000 square miles of the world’s ocean floors, along every continent except Antarctica. Typically preferring depths of less than ten feet, most seagrasses are modest in height, but some can reach 35 feet long, such as the showy, ribbonlike Zostera caulescens, which grows off the coast of Japan.

Seagrasses have survived, not just as species, but often as individual clones, for thousands of years. Scientists studying Posidonia oceanica meadows in the Mediterranean Sea estimate that the largest clone, which stretches more than nine miles, has been around, sending out slow-growing rhizomes, for tens of thousands of years, and possibly as many as 200,000 years. It could be the oldest-known organism on Earth.

Throughout these millennia seagrasses have not only greened undersea landscapes but have also actively shaped them—“ecological engineers,” as researchers say. Roots hold seafloor sediment in place. Leaves help to trap floating sediment, improving water clarity. Seagrasses slow currents and help protect shorelines from storms. And they efficiently filter out polluting chemicals even as they cycle nutrients, oxygenate the water and pull carbon dioxide into the seafloor. The new U.N. report estimates that seagrasses may perform up to 18 percent of the ocean’s carbon sequestration, even though they cover only about 0.1 percent of the ocean floor.

And they don’t do all this hard work silently. Carlos Duarte, a leading international seagrass expert at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, on the banks of the Red Sea, in Saudi Arabia, describes a “scintillating sound when you lie in seagrass meadows,” which comes from the bursting of oxygen bubbles seagrasses produce and which sound, he says, “like little bells.” These faint peals may serve as clarion calls to some creatures that rely on seagrass meadows. For example, fish whose larvae, floating through the water column in search of a suitable place to land and mature, may depend on the sound for guidance.

Like many other ecosystems, seagrasses are also facing rapid decline. Approximately 7 percent of global seagrass coverage disappears each year, similar to the loss of coral reefs and tropical rainforests. This decline also threatens species that depend on seagrasses for food and habitat, including endangered manatees, green sea turtles, chinook salmons, and dugongs, and it serves as a warning of greater devastation to come.

* * *

The assault on seagrasses comes in many forms. Fertilizer runoff fuels algae blooms, blocking the light needed for seagrasses to grow, as does excess topsoil runoff from coastal construction and development. Boat anchors and dredging uproot grasses and scar and fragment seagrass habitats. Overfishing large predators disrupts food chains, allowing mid-level predators to wipe out the worms and other small herbivores that usually clean algae off seagrasses. Rising sea temperatures threaten to outpace grasses’ ability to adapt or move, and exacerbate increasingly strong storms that can uproot entire meadows.

Seagrasses once thrived up and down the Eastern Seaboard of the United States. In some areas, such as the coastal waters off Virginia, meadows of Zostera marina, or eelgrass, were so abundant that, as recently as 100 years ago, local residents used clumps of the stuff that had washed ashore to insulate their homes. But in the 1930s seagrass meadows from North Carolina to Canada were practically eradicated, likely the result of a plague of slime mold disease combined with a devastating 1933 hurricane. Large swaths of coastal meadows had recovered by the 1960s, but important pockets remained barren.

A group of scientists, including Robert Orth, a marine ecologist at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, noted that there was no reason the region’s waters couldn’t sustain seagrass meadows once again. So the researchers had a wild idea: Why not reseed the historic eelgrass beds? Beginning in 1999, Orth and others dispersed 74.5 million eelgrass seeds into 536 restoration plots covering an area of close to a square mile. Now in its 21st year, it is one of the largest and most successful seagrass restoration efforts on the planet.

Soon new eelgrass meadows spread rapidly on their own; today, new growth covers nearly 13 square miles. Within a few years, new plots were hosting a diverse range of returning fish and marine invertebrates and were sequestering more and more carbon over time. “It’s a good-news story,” says Orth, who has been studying seagrasses for half a century. “If the plants aren’t challenged by water quality, they can spread naturally very quickly.”

Sites in Florida as well as Europe and Australia have also succeeded in reviving seagrass populations, even with passive restoration efforts such as reducing fertilizer and soil runoff.

New international efforts are also underway to create an up-to-date map of seagrass colonies all over the world—a baseline for assessing what we stand to lose. “Getting an accurate global map of seagrass distribution is really important for understanding the fisheries that depend on them as well as their contributions to carbon storage,” says Duffy, of the Smithsonian.

Duffy and his colleagues are using drone imagery to study seagrasses along the North American Pacific Coast, where new outbreaks of slime mold disease, possibly fueled by warming ocean temperatures, threaten large seagrass meadows. Citizen scientists are pitching in, reporting seagrass locations with the smartphone app SeagrassSpotter. Duarte and others are even enlisting the help of radio signal-tagged creatures. “We are finding seagrass meadows by collaborating with sea turtles and tiger sharks,” Duarte says.

Researchers are increasingly convinced of the value in working to expand seagrass beds, not just for the grasses’ own sake or for the marine creatures that depend on them, but for our own well-being. “If we invest in seagrasses, they can help us in lowering the global concentration of carbon dioxide,” says Jonathan Lefcheck, a research scientist at the Smithsonian’s Environmental Research Center. He notes that we are quick to recognize the importance of forests in keeping carbon out of the atmosphere. But a seagrass meadow can be just as effective as a temperate forest in sequestering carbon, sinking it into the sediment for decades or even centuries. “I’m pitching seagrasses as an ally in climate change,” he says. “They are an incredible ecosystem that continue to provide a wealth of benefits to humanity.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6a/34/6a3491a7-c47d-4469-a8d8-faa2b70fc7ac/mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/b7/d1b7f6ab-b2e3-46da-aeed-7fd2941a1e63/opener_-_white.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/5b/975b84bd-ed5c-4be5-8deb-e257e9b2ecba/dec2020_h21_seagrass.jpg)