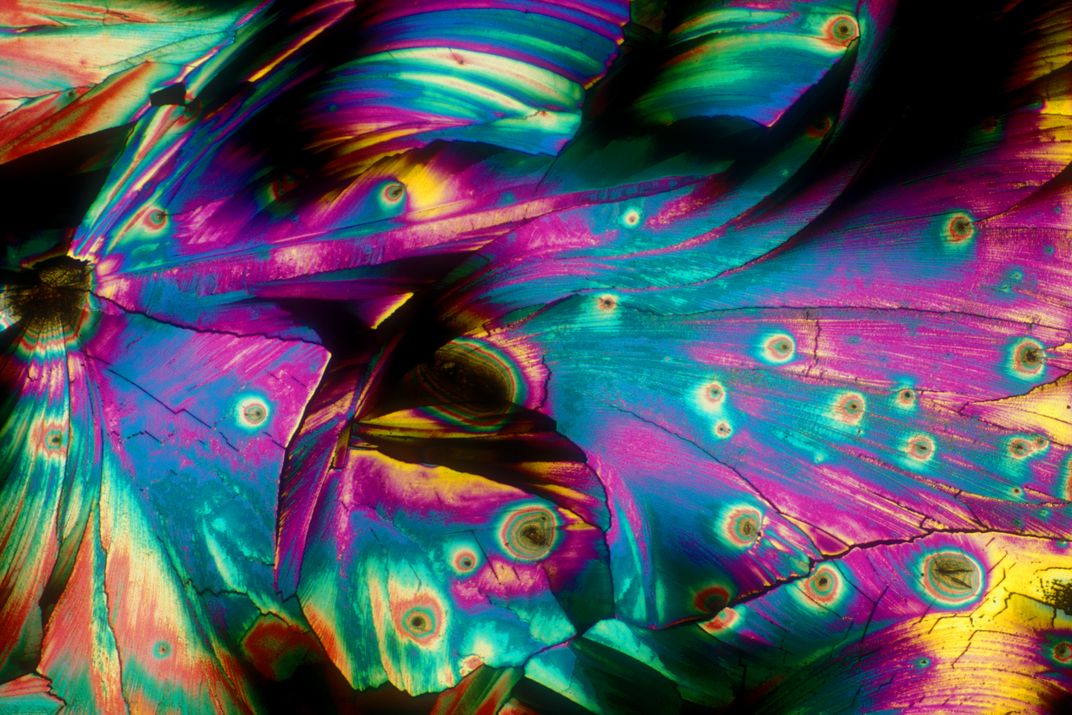

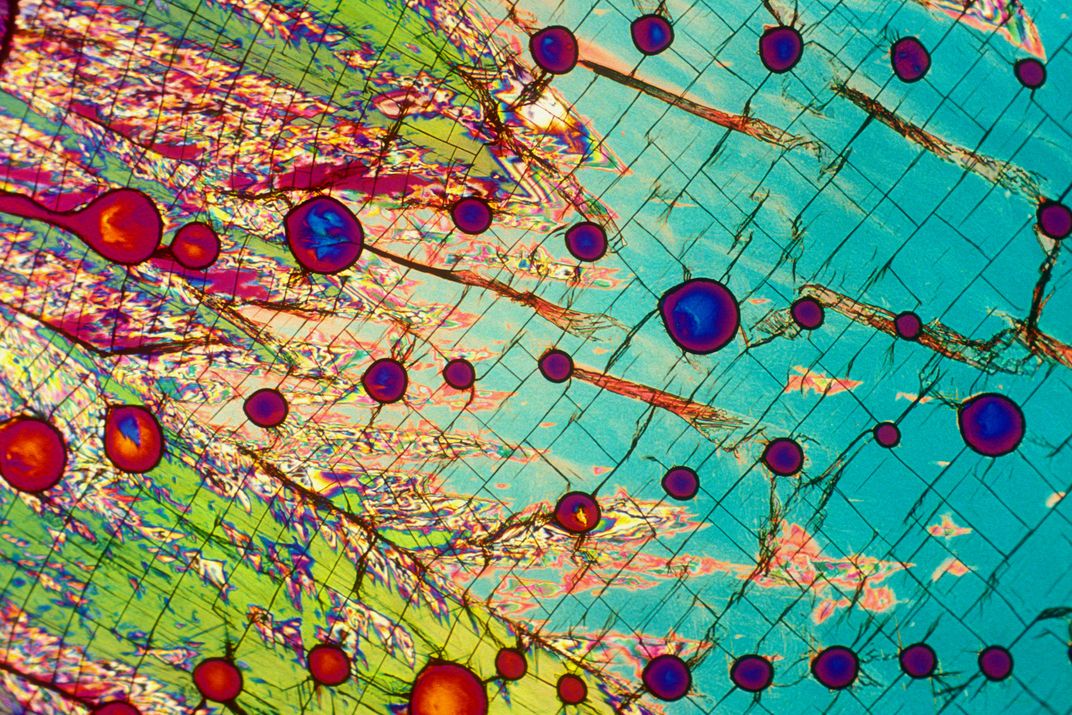

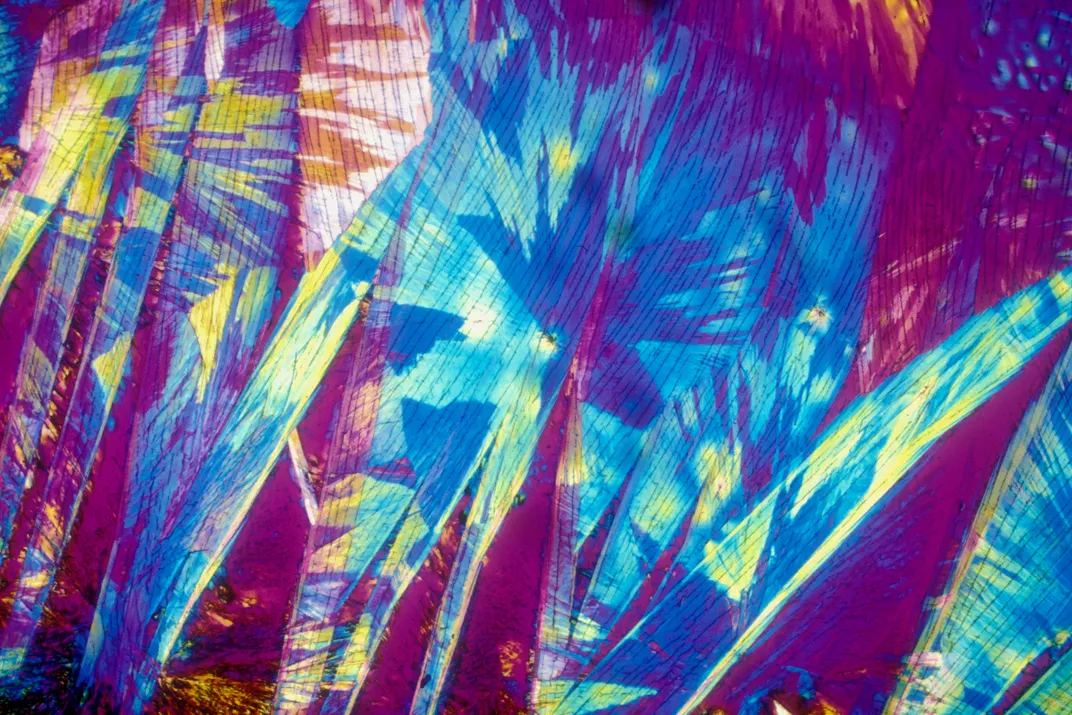

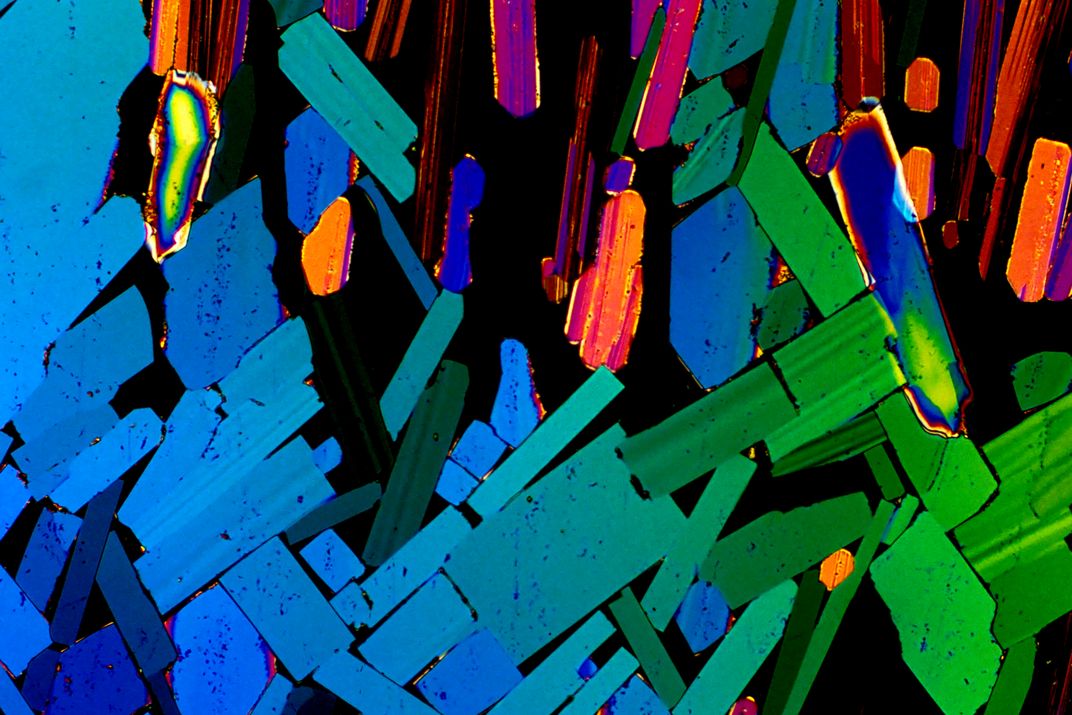

What Does Your Favorite Drink Look Like Under A Microscope?

Check out these colorful images of crystallized alcoholic beverages

Mixologists can be quite crafty with their concoctions, straining bourbon into glasses smoked with pipe tobacco or garnishing rum with flecks of edible gold glitter. But can alcoholic beverages themselves—wine, beer, liquor and cocktails—be considered works of art?

To Lester Hutt, president of BevShots, the answer is a resounding yes. Hutt, who holds a Bachelors degree in biology and chemistry as well as a Masters in analytical chemistry from the University of California, Berkeley, was working as a consultant at Florida State University, helping the school pinpoint science projects that might springboard into successful businesses, when he came across the work of Michael Davidson, a world-renowned microscopist, in 2008. Davidson had some moderate success selling images of crystalized drinks to a company that sold neckties; together, Davidson and the tie company sold 2 million cocktail-themed neckties (dubbed "The Cocktail Collection") in the 1990s, before fashions changed.

"I thought to myself that this could do very well as a modern art line," Hutt says of Davidson's photographs. "What was nice about it was the images were already all taken; there’s no research that had to go into it."

Hutts's suspicion has proven true. For the past four years, BevShots has grown into a successful business, printing the images onto metallic photo paper or items like scarves. "Most of our photos are of alcoholic beverages, and that goes without saying that a lot of people enjoy the occasional cocktail. People like the idea of having modern art that can be easily explained by saying 'That's my favorite drink under a microscope,'" Hutt says.

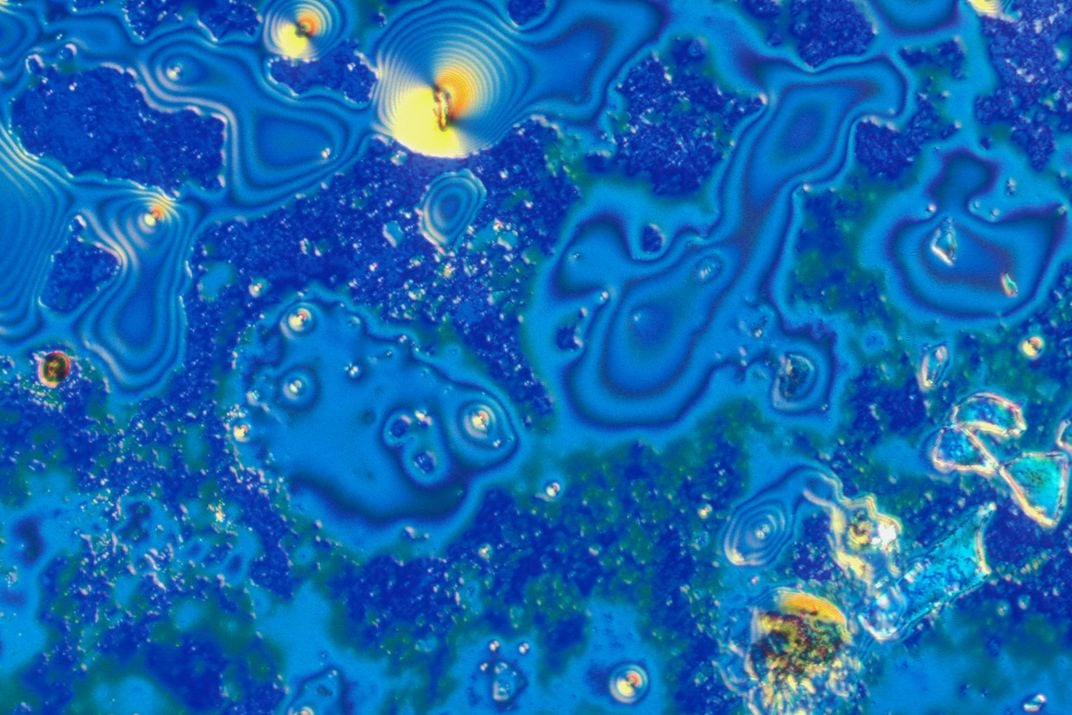

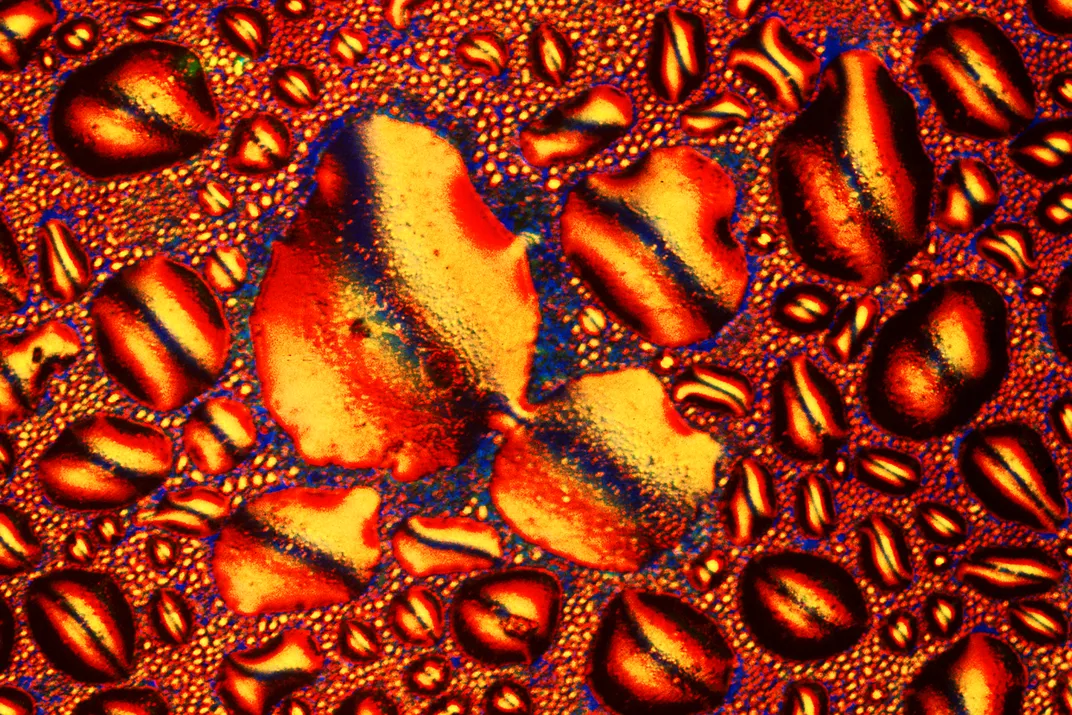

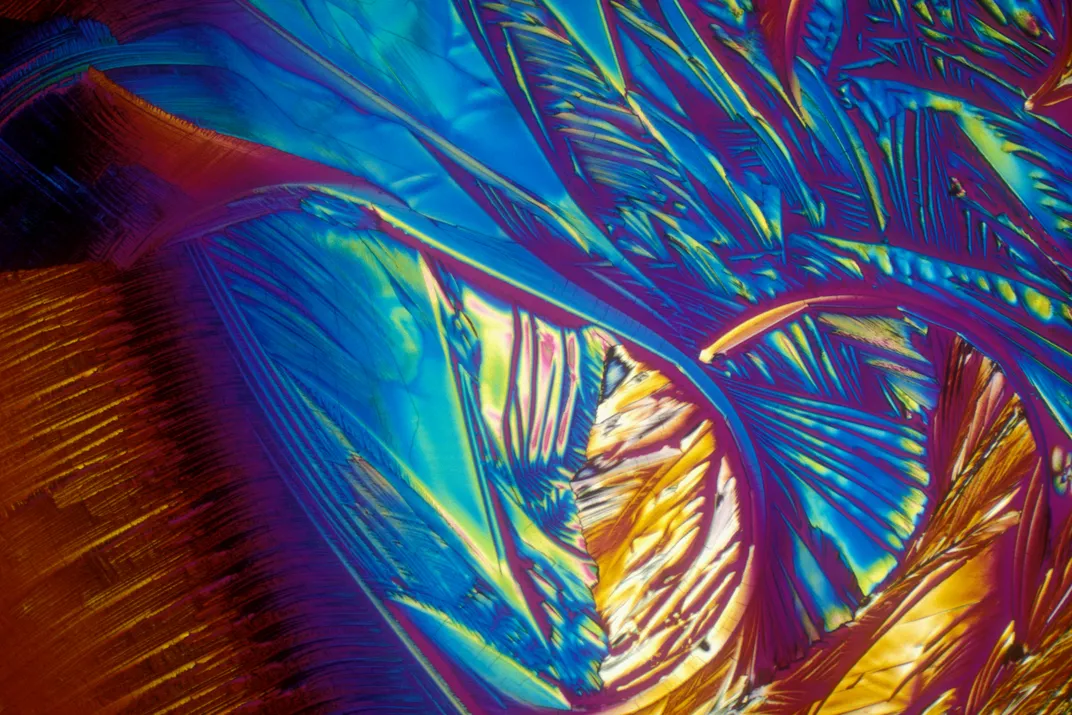

Davidson produced the images by photographing drink crystals with a standard light microscope fitted with a camera and two polarizing filters. He used no dyes or Photoshop. The light passing through the crystals produces the rainbow colors.

When you look at a photograph, it might seem like you're glancing into the molecular structure of the beverage. This isn't the case—you're looking at a crystallized form of the drink, which Davidson achieved by letting a drop of the liquid dry out on a microscope slide. For some drinks, like a piña colada or a margarita, with ingredients other than pure alcohol in them, the crystallization process was fairly straightforward, because the presence of various other particles (like sugar or salt) helped crystals form. But with other drinks, especially spirits like whiskey or vodka, coaxing crystals proved challenging at times. Depending on how difficult it is to crystallize the drink, capturing the crystals on camera took anywhere from four weeks to six months.

"If you look at some of the hard liquors, the crystals on those just didn’t form as well as the margarita or martini, because there wasn’t as much dissolved in it to crystallize out. If you have very pure vodka, really all it’s going to be is ethanol and vodka," Hutt explains. "Those crystals are not as well defined."

Davidson applied a technique known as polarizing light microscopy, often used in geological sciences when thin cross-sections of rock are being examined for their composition. Polarizing filters work by taking normal light waves, which traditionally vibrate in all directions, and forcing them to vibrate in one direction. When two polarizing filters are set at a 90-degree angle from one another, they block the passage of light completely.

The microscope Davidson used to capture his images of the drink crystals had two polarizing filters, one right before the light source hit the sample and another, rotated 90-degrees, right after the sample. Light passing through the crystals refracted, like in a prism, producing the vibrant colors and shapes seen in the images. Anything that isn't a crystal, however, appears completely black. In a BevShots image of tequila, for instance, the crystals' jagged edges starkly contrast against the black background.

Like snowflakes, no two drinks crystallize alike, Hutt explains. "People say that it is just 'cool!'" he says. "I've been trying to find another way of explaining this, but 'cool' is honestly the best word to describe these photos."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)