American Bugs Almost Wiped Out France’s Wine Industry

When the Great French Wine Blight hit in the mid 1800s, the culprit turned out to be a pest from the New World that would forever alter wine production

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/78/09784112-5ee1-46cc-b6b0-7c4eb8bc26d5/42-27713886.jpg)

Around 150 years ago, France’s reputation as one of the world’s greatest producers of wine was under critical threat from a terrible blight. When scientists were finally able to determine the cause, they found the blame lay with a tiny parasitic insect that traveled over from the United States.

But it wasn’t really all America’s fault; the French had imported the problem themselves, albeit unknowingly—and the impact on the wine industry would be momentous.

Levi Gadye over at io9 recently shared a fascinating exploration of just how “the Great French Wine Blight Changed Grapes Forever.” Here's the story: As the global wine industry picked up speed in the 18th and 19th centuries, French vintners began to import American vines to ensure that their vineyards remained competitive. (After all, Americans had imported the French variety for centuries.) “Amidst all the excitement surrounding the growing wine economy, the vine importers failed to notice a stowaway on their cargo,” writes Gadye.

By the mid 1860s, an “unknown disease” began to destroy entire vineyards, causing grape vines to rot away, fruit and all. It crippled wine production and threatened the future of the whole industry.

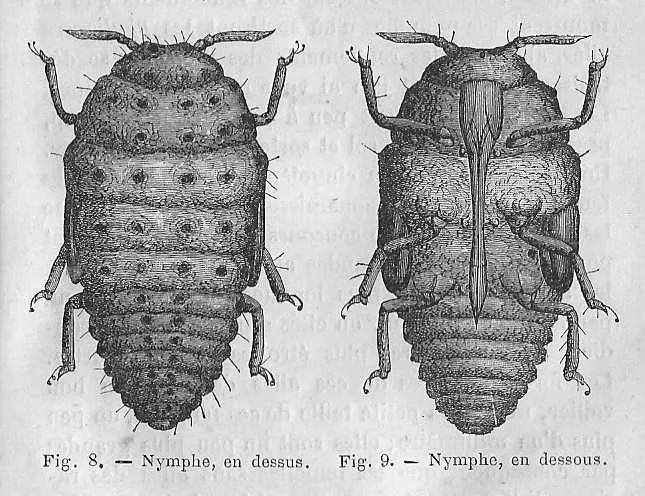

The scientists sent to investigate eventually discovered that the plants were the victims of tiny, gross "louse of yellowish color" that were feasting on living vine roots, irreparably damaging them. After much debate the insects were identified as an American aphid-like bug called phylloxera. In the U.S., though, they only bothered the leaves of grape vines, where they were nowhere to be found on French plants.

Finally, writes Gadye, it was discovered that “the phylloxera preferred the leaves of imported American vines, and the roots of local French vines.” The French government offered 300,000 francs to anyone who could create an effective insecticide. But by the 1890s, when all other efforts seemingly failed, they started the long process of “developing hybrid or grafted vines that could thrive in French soils; resist phylloxera; and still make great wine.”

So, they grafted French vines onto American rootstocks, as well as creating full hybrids. Now, notes Gadye, “nearly all French wine, including expensive French wine, comes from vines grafted onto American roots.” That’s right: the U.S. has a hand in some of Europe’s most venerated vintages.

The wine blight that hit France would sweep the globe, with Chile being the only major wine producer to escape damaging infestation from the bad bug for reasons still speculated today. And we still aren’t free and clear of the blight—it reared its head again in California during the 1980s, causing about $1 billion in damage.

Yet, writes Gadye, there are a couple French vineyards that managed to escape damage from phylloxera for reasons that are still “a complete mystery.” You can bet that the prized wine from those locales cost more than a pretty penny.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lauraclark.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lauraclark.jpeg)