Archaeologists Find Shot Glass Shards, Anti-Witch Carving at Centuries-Old Scottish Pub

At the time of its construction, the Wilkhouse Inn was considered a “statement of modernity and affluence”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/17/e0174c5a-e4d5-4f5f-915c-e1910e50a0a5/wilkhouse5-inverted-cross-inscription-1024x768.jpg)

When Reverend Donald Sage visited the Wilkhouse Inn in 1802, he wrote admiringly of its “bustling helpmeet,” hearty dinner offerings, and spacious parlor, which acted as a “general rendesvous [point] for all comers of every sort and size.” At the time, the Wilkhouse—a boarding house and pub in Brora, Scotland—exemplified all that a modern inn should be: While other lodgings had thatched roofs, central hearths and wood-shuttered windows, the Highlands establishment boasted double chimneys, a slate roof, glass windows and similarly advanced features.

Despite its popularity, the once-thriving inn was all but abandoned within years of Sage’s visit. Around 1819, a series of financially motivated land clearances led to the Wilkhouse’s forcible closure, and by 1870, the Scotsman’s Alison Campsie writes, the building was essentially a “ruin marked on a map.”

A new survey published in Archaeology Reports Online outlines the results of excavations at the inn, detailing finds including coins, animal remains, an inverted cross carving and glass shards. Per the report, the carving was likely inscribed on the Wilkhouse’s hearth in hopes of discouraging witches from flying down the chimney; the glass fragments, meanwhile, evoke images of “toasts being exchanged after a meal or drinking session, with the noise of the glasses being slammed down on a table echoing through the inn.”

A statement from Guard Archaeology, the Scottish firm tasked with overseeing excavations, notes, “The evidence reveals a place pivotal to the local economy, where the continuity of settlement within the Highlands was in the process of developing into modernity before being cut short by the clearances.”

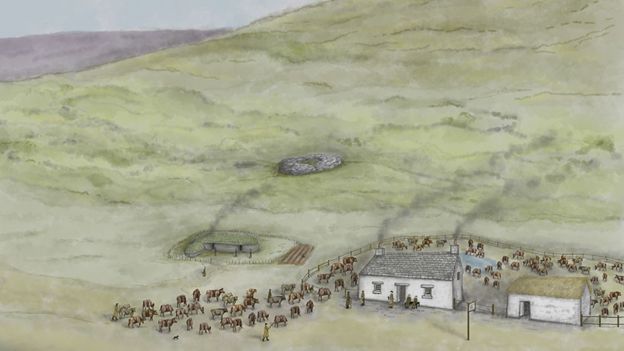

According to BBC News, the Wilkhouse—described by Guard Archaeology as a “statement of modernity and affluence when it was built in the [18th] century”—benefitted from its prime location. Situated next to a drove road, or route used mainly by merchants transporting cattle, the inn initially welcomed enough patrons to justify its hefty construction and maintenance costs. Artifacts found at the site, from rabbit and bird bones to mollusk shells, soldiers’ buttons, buckles, thimbles and a comb, paint a portrait of a lively hub frequented by locals and travelers alike.

The most important figure in the Wilkhouse’s untimely demise was the Duke of Sutherland, a local aristocrat whose family had long overseen the land on which the inn stood. Spurred by a desire to replace locals with revenue-generating sheep farmers, Sutherland ordered his estate—including residents and businesses alike—cleared around 1819.

If the Highland Clearances had not led to the Wilkhouse’s closure, it’s likely the inn would still have fallen victim to regional development. Per the report, a new road built to better serve wheeled traffic directed travelers away from the building, winding so far up a hill that the inn could no longer be seen from the street. Larger, newer lodgings built in Brora and neighboring villages also added to the pressure.

As historian Donald Adamson tells the Scotsman, “The inn was not to be spared, and by the coming of the railway in 1870 had sank into obscurity and was little more than a ruin.”

Adamson cites Reverend Sage’s account, published decades after his initial visit, as a powerful image of “what was lost when the inn was forcibly closed in the name of improvement.”

In Sage’s own words, host Robert Gordon, or “'Rob tighe na faochaig,’ as he was usually called, [welcomed us] with many bows indicative of welcome, whilst his bustling helpmeet repeated the same protestations of welcome on our crossing the threshold.”

“We dined heartily on cold meat, eggs, new cheese, and milk,” the reverend adds. “Tam, our attendant, was not forgotten; his pedestrian exercise had given him a keen appetite, and it was abundantly satisfied.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)