How the Belize Barrier Reef Beat the Endangered List

An oil drilling moratorium, development restrictions and fishing reform has helped the 200-mile-reef come off Unesco’s endangered world heritage sites list

This week Unesco, the United Nation’s scientific and cultural agency, removed the Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System, part of the 600-mile long MesoAmerican Reef System, the world’s second largest, from its list of endangered world heritage sites. And, surprisingly, it’s not because the reef is so degraded or damaged that it can’t be saved. The BBC reports that instead, after a decade of “visionary” work to protect the reef, Unesco believes it’s safe for the time being.

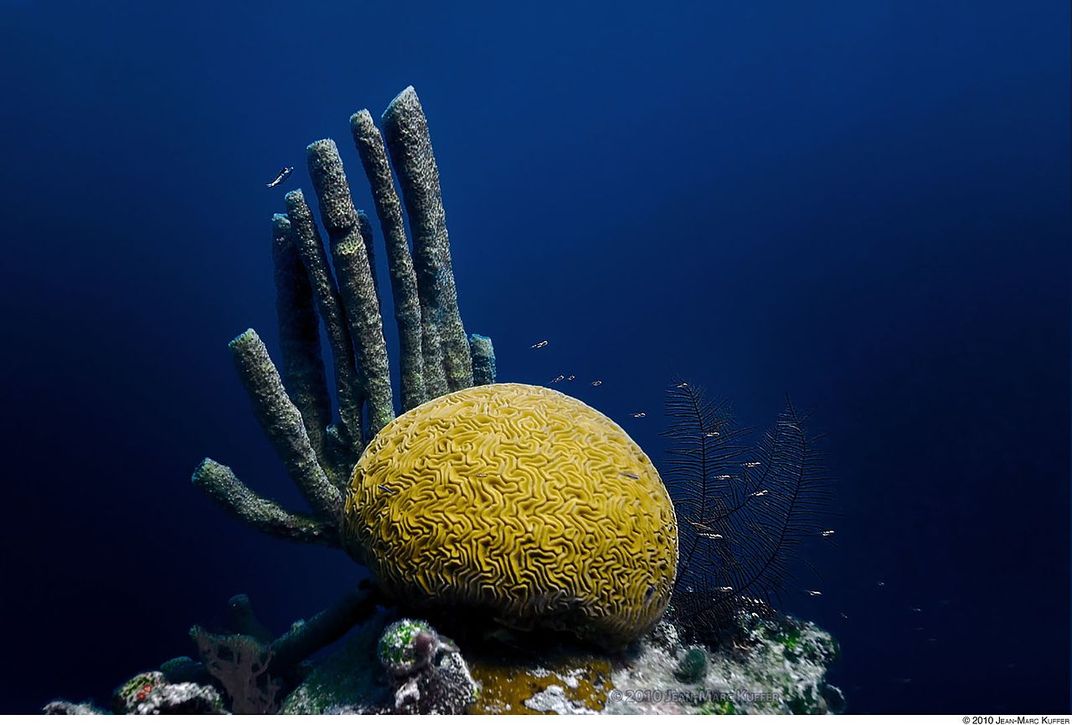

According to a press release, the roughly 200-mile-long reef was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1996, but in 2009, due to a spate of threats, it was added to the agency’s endangered list. In particular, the possibility of offshore oil drilling near the reef, the rapid destruction of mangrove forests and coastal development all threatened to degrade the reef system, which in addition to being part of the largest reef in the northern hemisphere, is also home to threatened species including sea turtles, manatees and crocodiles.

Tryggvi Adalbjornsson at The New York Times reports that the reef was struck from the list because, at least for now, all of those threats have abated. “In the last two years, especially in the last year, the government of Belize really has made a transformational shift,” says Fanny Douvere, coordinator of Unesco’s marine program.

Tik Root at National Geographic reports that public concern for the reef blossomed in 2011 with the revelation that the government quietly sold off oil leases for the entire seabed. Activists pushed back, and in 2012 they gained enough signatures on a petition to force a national referendum on oil drilling. But when the government refused to issue the referendum, claiming thousands of the signatures were illegible, activists organized their own "people's referendum.”

AFP reports that 96 percent of people in the informal vote chose to protect the reef instead of allowing offshore oil drilling. The following year, the Supreme Court of Belize ruled that the oil contracts were illegal because they did not follow the required environmental impact procedures. After that, the political tide turned. In 2016, the government announced a formal policy to ban offshore oil drilling in the seven marine parks that make up the Belize Barrier Reef Reserve. Then, last December, the government announced a ban on offshore drilling in all of its waters. This summer, strict regulations on the cutting of mangroves also went into effect. Unesco has praised the efforts as a “visionary plan to manage the coastline” and “the level of conservation we hoped for has been achieved.”

Root reports that Belize has made other changes as well, including new environmental taxes to support the reef, restricted fishing of sensitive species like parrot fish and efforts to limit foreign fishing trawlers. It has also boosted its no-fishing zones from 3 percent of its waters to 10 percent. Next year, the government has announced plans to ban all single-use plastics, which have also polluted the reef.

While all of that is great news for Belize, Root points out that the reef still faces challenges from increasing cruise-ship tourism and development, an invasion of lionfish, which decimate other tropical species, and pollution runoff.

And Adalbjornsson points out that, like all reefs in the world, the ecosystem faces major challenges from climate change, including increased water temperature and bleaching events, ocean pollution and acidification. “The primary threats are all still there,” John Bruno, a marine ecologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, says. “The big one, of course, is ocean warming.”

Root reports that bleaching along the reef has become an annual event, with 40 percent of study sites affected last year alone. In fact, recent research shows that all reef systems should expect major bleaching events at least once a decade and that as ocean temperatures continue to climb due to climate change, they may become even more frequent. The Great Barrier Reef, off the coast of Australia, has already been irreparably changed by climate change, with half of its corals killed by back-to-back bleaching events between 2015 and 2017.