Aboriginal Australians Dined on Moths 2,000 Years Ago

The discovery of an ancient grindstone containing traces of the insect confirms long-held Indigenous oral tradition

:focal(377x304:378x305)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/26/ac26dafc-12af-43ce-b1c8-49636029d5d0/bogong_moth.jpg)

A collaboration between researchers from Monash University and traditional land owners of the Gunaikurnai people has uncovered tools used to prepare Bogong moths as food in what’s now Victoria, Australia, some 2,000 years ago.

“We have oral histories about eating the Bogong moth in our culture, but since early settlement a lot of that knowledge has been lost, so it’s exciting to use new technologies to connect with old traditions and customs,” Elder Russell Mullett, a traditional land owner who was involved in the research, tells the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC) Jedda Costa.

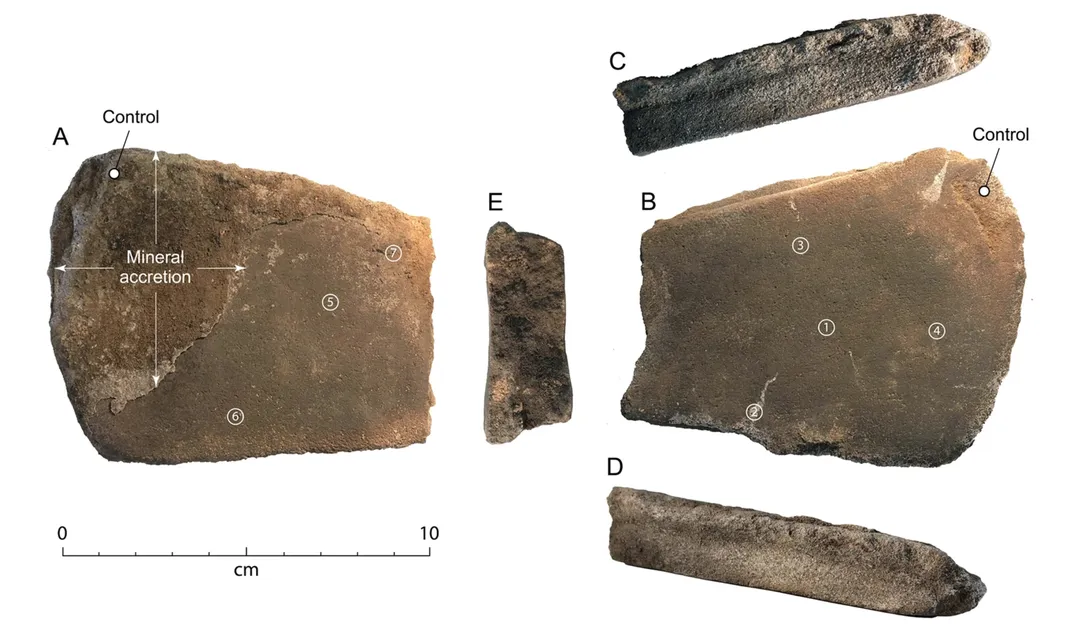

In 2019, the team excavated Cloggs Cave, near Buchan in eastern Victoria, for the first time in 50 years. Inside, researchers found a small, roughly 11-ounce grinding stone dated to between 1,600 and 2,100 years ago. They used a technique known as biochemical staining to identify collagen and protein remains from Bogong moths on the stone—the first conclusive archaeological evidence of insect food remnants on a stone artifact in the world, according to a statement. The findings are outlined in the journal Scientific Reports.

As Ethan James reports for the Canberra Times, the grindstone was portable enough for ancient Indigenous people to carry it on their travels. Its owners may have used the stone to grind the insects into cakes or pastes that could then be smoked and preserved. Another popular cooking technique was roasting the moths in a fire.

The tool’s discovery confirms long-held oral histories, showing that Aboriginal families have harvested, cooked and feasted on Bogong months for upward of 65 generations.

Written settler histories note that locals harvested the insects between the 1830s and ’50s. As Diann Witney of Charles Sturt University told the ABC in 2002, Indigenous people from many different societies would gather for ceremonies during the moth harvest. But the festivals came to an end within three decades of European colonists’ arrival in the region during the late 18th century, says Bruno David, an archaeologist with Monash University’s Indigenous Studies Center who helped lead the new investigation, in the statement. Indigenous Australians revived the tradition in the 20th century, creating what became the Bogong Moth Festival, or Ngan Girra Festival.

Pettina Love, a member of the Bundjalung Nation Aboriginal community who conducted a study about the safety of eating the moths when she was a PhD student at La Trobe University, noted in 2011 that some people continue the practice today.

“The favored method of cooking is BBQ,” she said in a statement. “Opinions vary about the taste. Some people report a peanut butter flavor and others saying they have a sweet aftertaste like nectar.”

Love’s work concluded that concerns previously raised about levels of arsenic in the moths were unjustified, meaning the insects are safe to eat. Per ABC, moth populations in the area have dropped due to factors including low rainfall, pesticides and light pollution.

Mullett says the specific tradition of traveling to Cloggs Cave and the surrounding mountains for the Bogong season disappeared many years ago.

“Because our people no longer travel to the mountains for Bogong moth festivals, the oral histories aren’t shared anymore,” he adds. “It’s a lost tradition.”

Cloggs Cave’s use by humans goes back about 17,000 years. ABC reports that an academic team previously excavated the cave in 1972 without input from traditional owners. Comparatively, the Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation, the organization of the Gunaikurnai people, initiated the new research effort.

“Aboriginal people know their cultures better than anyone else,” David tells ABC. “That’s why listening and good partnership is so important because it’s not up to us to tell people what to do with their histories.”

David notes in the statement that culinary traditions are central expressions of cultures around the world.

“The absence of an iconic Aboriginal food from the archaeological record is tantamount to the silencing of Aboriginal food cultures,” he says. “Now we have a new way of bringing it back into the story.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)