Scientists Search for the Most Dangerous Places to Be a Shark

In a bid to stop the populations from dwindling, scientists are turning to big data

Sharks may be top predators in the ocean, but they’re no match for human activity. People kill between 63 million and 273 million sharks per year—from deaths due to the shark-fin trade to creatures caught as bycatch of vessels seeking other creatures.

But saving sharks is no easy feat. There are around 400 species of sharks in the world and there is still much more to learn about these elusive beasts, including their populations, feeding areas, birthing grounds and more.

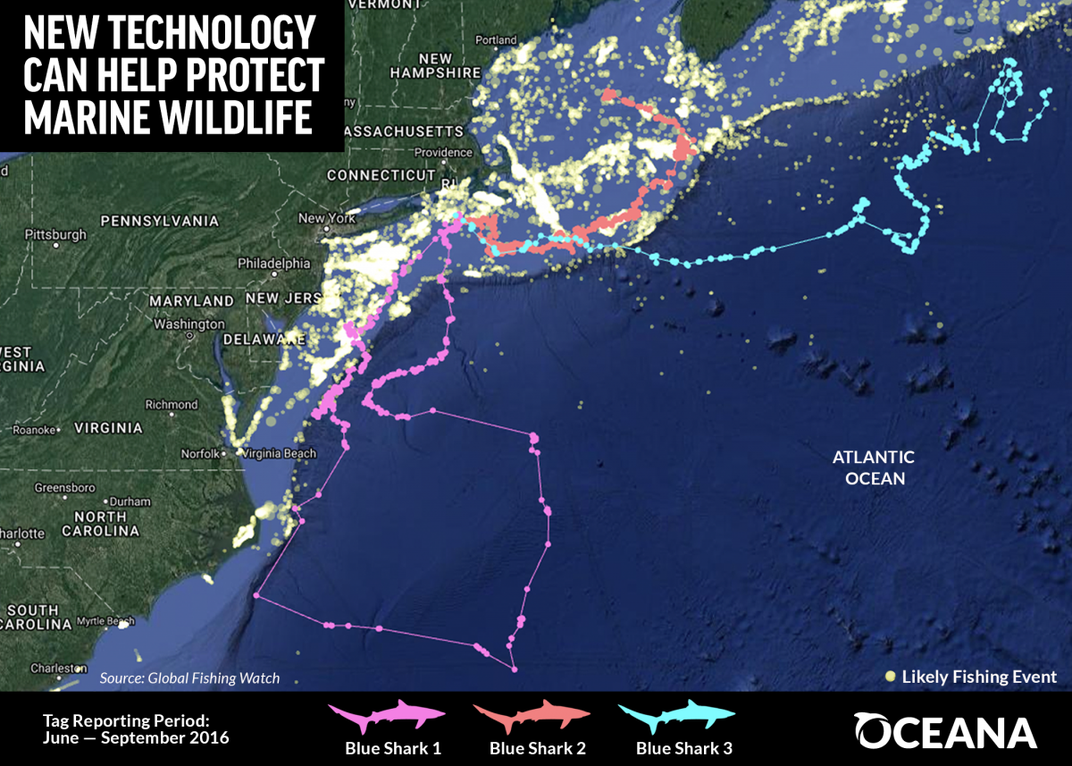

That’s where the marine conservation group Oceana steps in. In September, 2016, Oceana debuted an online data platform called Global Fishing Watch. The system uses signals broadcast from boats to identify all the ships at sea in hopes of protecting our marine menagerie. An algorithm combs though billions of these signals to map the paths of vessels and determine which ships are actively fishing, Emily Matchar at Smithsonian.com reported earlier this year. That data can be used by researchers and conservationists to learn about the size, location and techniques used by the global fishing fleet—even identify possible illegal fishing methods.

But in their latest addition to the system, laid out this week in a new report, the group is using overlays of shark data to identify hotspots where the human and marine life collide. But to do this, they needed to tag some sharks.

Oceana partnered with Austin Gallagher, marine biologist at the conservation NGO Beneath the Waves, and Neil Hammerschlag, biologist at the University of Miami, to tag blue sharks in the Nantucket Shoals.

Blue sharks can grow up to 10 feet long and can be found all around the world. While they have no commercial value, blue sharks are the most commonly caught shark species, making up 50 to 90 percent of the sharks accidentally caught by longline fishing vessels in some regions.

The team tagged ten sharks with SPOT-6 transmitters on their dorsal fins during the summer of 2016, recording data between 29 and 68 days. They imported the information into Global Fishing Watch. The results suggest that over a 110-day period, one shark came within a half a mile of a fishing vessel while another shark came within a tenth of a mile of three vessels believed to be actively fishing.

As Beth Lowell, Oceana’s senior campaign director, tells Smithsonian.com, the initial work is a great proof of concept—and she hopes to start collecting more data. “With 10 sharks it’s hard to come up with a groundbreaking revelation,” she says. “But as more data is ported into the tool, more trends will arise and researchers will be able to see in time and space how sharks operate among fishing activity.”

In the future, fisheries managers could use the system to avoid or limit fishing in hotspots where sensitive species gather. “If we know there is a big nursery where sharks are pupping at a certain time of year, managers can say ‘Let’s avoid these areas right now,” she says.

Protecting these species is critical. The removal of the ocean’s top predators cascades through marine ecosystems. According to some studies, the loss of sharks could lead to a reduction in commercial fish, since sharks often keep mid-level predators in check. Recent research even suggests sharks help keep "blue carbon" locked in the oceans, influencing climate change.

As Lowell explains, they hope scientists can help continue to build the database with historical tracking data. To ensure accuracy they are only using tracking data dating back to 2012. “Improvements in satellite tags and the quality of the data will help this grow exponentially,” says Lowell.

Oceana hopes news of the tool will spread quickly, and that scientists tracking animals in the field will begin sharing their past and future information—including data on other species of sharks as well as sea turtles, marine mammals and fish. “We’re hoping this report will ring the bell with the research community,” Lowell says.