Opening Warm Champagne Leads to a Pop of Blue

This flash of color is caused by the same process that colors the sky with its blue hues

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/98/d1989e9b-0ac0-438d-9b2b-a91618097d2b/champagne_pops-1.jpg)

It's a sound that marks many a boisterous gathering: the pop of a champagne bottle.

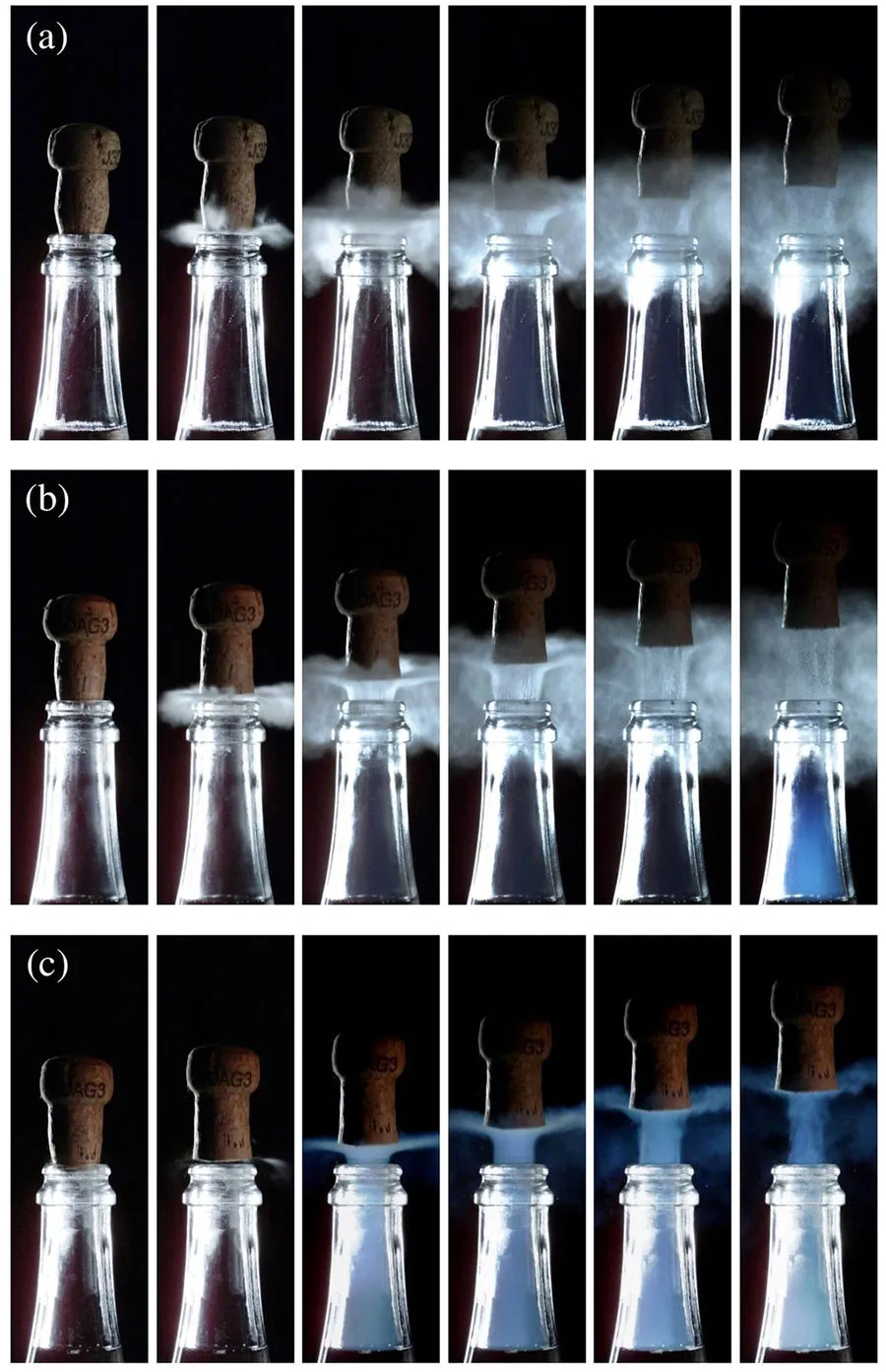

If that bubbly was chilled to the proper 43-54 degrees Fahrenheit, the noise is accompanied by a cool white smoke rolling out of the bottle's thin neck. But a new study shows that this mini-cloud is even cooler if the champagne is warm—turning briefly blue at 68 degrees Fahrenheit, reports Sara Chodosh at Popular Science.

Using a high-speed cameras, researchers at the University of Reims-Champagne Ardenne recorded what happens when you open bubbly chilled to different temperatures. And the results, published last week in the journal Scientific Reports, are a little counterintuitive.

The white cloud seeming to emanate from chilled champagne isn’t trapped gas shooting out of the bottle. It’s actually water vapor from the air outside the bottle. When the trapped CO2 inside the bottle is released, it rapidly expands, casing the temperature to drop in a process called adiabatic cooling. That temperature drop is so severe, it causes water vapor to condense in the air, creating the cloud around the bottle. In fact, the cloud is not rolling out of the bottle, it’s flowing into the bottle, writes Chodosh.

But when the researchers turned their cameras to the 68-degree, room temperature bottles of champagne, however, they found something even stranger. As Laurence Coustal at Agence France-Presse reports, the smoke from the bottle turns sky blue for a few milliseconds. According to the study, the smoke also first appears in the bottleneck itself, and the fog produced lasts a much shorter time and has less volume than vapor produced by the chilled bottles.

That’s because at the higher temperature, the pressure inside the bottle is higher. This means that the adiabatic cooling even more extreme during carbon dioxide release. “Bottles at 20 C [68 F] were under such a pressure (in the order of eight bar) that the adiabatic expansion allowed the temperature of the escaping gas to plummet to a glacial temperature of minus 90 C (minus 130 Fahrenheit),” study co-author Gerard Liger-Belair tells Coustal. Because this frigid temperature lies below the freezing point for carbon dioxide, the researchers hypothesize that the blue cloud forms as tiny particles of dry ice form. Light reflects off those icy particles creating the blue hue.

“This blue cloud has the same physical origin as the blue color of the sky. Is that not extraordinary?” Liger-Belair tells Coustal. “It is simply a beautiful physics experiment done with a familiar product. Who would have thought that in a few milliseconds, we would find such extreme conditions during the opening of a bottle of champagne?”

This is not the first time the same team has examined champagne with high-speed cameras. The researchers have previously studied how the physics of champagne bubbles affect the look, feel and flavor of the drink, and how glassware impacts its flavor (they are decidedly team flute). And champagne isn’t the only adult elixir to get the scientific treatment. Last month, a team of researchers determined that adding a splash of water to whiskey improves its flavor, and physicists have also studied the residue left over in whiskey glasses to glean insights on fluid dynamics.

So next time you open a bottle of bubbly, consider the chemistry that takes place after the pop.