Quaker Oats to Retire Aunt Jemima After Acknowledging Brand’s Origins as ‘Racial Stereotype’

The breakfast line’s rebranding arrives amid widespread protests against systemic racism and police brutality

:focal(2404x1404:2405x1405)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/85/d285090d-0936-4e5a-ad3a-59933f2058c8/aunt_jemima_syrup_2020.jpg)

On Wednesday, Quaker Oats announced plans to remove the Aunt Jemima name and image from its products, including pancake mix, syrup and other breakfast foods. The decision, which comes amid widespread protests against police brutality and institutional racism, arrives just days after a video detailing the 131-year-old brand’s history went viral on social media, reports Tiffany Hsu for the New York Times.

In a statement, Kristin Kroepfl, vice president and chief marketing officer at Quaker Foods North America, acknowledged that “Aunt Jemima’s origins are based on a racial stereotype.”

She added, “While work has been done over the years to update the brand in a manner intended to be appropriate and respectful, we realize those changes are not enough.”

Quaker Oats—a subsidiary of PepsiCo since 2001—has made numerous tweaks to Aunt Jemima’s image over the decades, removing her kerchief in 1968 and giving her pearl earrings and a lace collar in 1989. More recently, notes the Times, a 2016 rebranding campaign yielded such suggestions as changing the character’s name to “Aunt J,” inviting artists to design a new likeness and adding to her backstory.

“The decision to discontinue the Aunt Jemima brand comes as this discourse regarding black lives elevates and continues to gain momentum,” says Kevin Strait, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture. “Based on the mammy archetype from blackface minstrel shows from the 19th century, the image of Aunt Jemima is an historical embodiment of racist caricature that is thoroughly entrenched in the shared memory and language of American popular culture.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/7b/f27b5aef-c37f-4112-aaa5-561ed336f20c/14908157871_cee6d443f1_c.jpg)

Aunt Jemima’s ready-made pancake mix first appeared on shelves in 1889. Named after the minstrel song and character “Old Aunt Jemima,” the company floundered financially and was acquired by milling company owner R.T. Davis just two years after its creation.

Davis chose Nancy Green, a cook and former enslaved individual born in Kentucky in 1834, to portray the character and act as a spokesperson for the brand. According to Marilyn Kern-Foxworth’s Blacks in Advertising, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, Green won fame after appearing as Aunt Jemima at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. She went on to travel the country in promotion of the breakfast line.

Cook and former sharecropper Anna S. Harrington started playing Aunt Jemima in 1935. Speaking with Conor Wight of CNY Central, Robert Searing, curator of history at the Onondaga Historical Association, says, “She became a national celebrity, getting flown around by Quaker Oats [and] giving pancake demonstrations across the country.”

In 2014, two of Harrington’s great-grandsons sued Quaker Oats for failing to pay royalties to Green and their great-grandmother, who they credit with helping to formulate the self-rising pancake mix’s recipe, as Jere Downs reported for the Courier Journal at the time. The case was later dismissed by a judge.

As protests and calls for accountability sweep the nation, corporations have started to publicly reckon with their roles in perpetuating racism, writes Chauncey Alcorn for CNN. NASCAR, for instance, recently banned the presence of Confederate flags at its events. And other major food brands are starting to place their controversial imagery under review, too: Mars is set to retire the Uncle Ben’s rice logo; B&G says it will revisit its Cream of Wheat packaging; and Conagra, the corporation that makes Mrs. Butterworth’s syrups, is launching a “complete brand and packing review,” reports Emily Heil for the Washington Post. (In April, Land O’Lakes said it would retire Mia, the indigenous woman once featured prominently in its iconic logo, from all packaging, but did not directly address her departure in its rebranding announcements.)

“We’re experiencing this extraordinary moment in history where the very subject of black lives has become a central part of our shared national discourse,” says Strait. “ … It’s a broad demand for justice and sweeping change that targets not just the policing of black neighborhoods, but all aspects of African American life, including the anachronistic symbols, monuments and iconography that have historically framed the racist and stereotypical ways that black people are viewed and treated.”

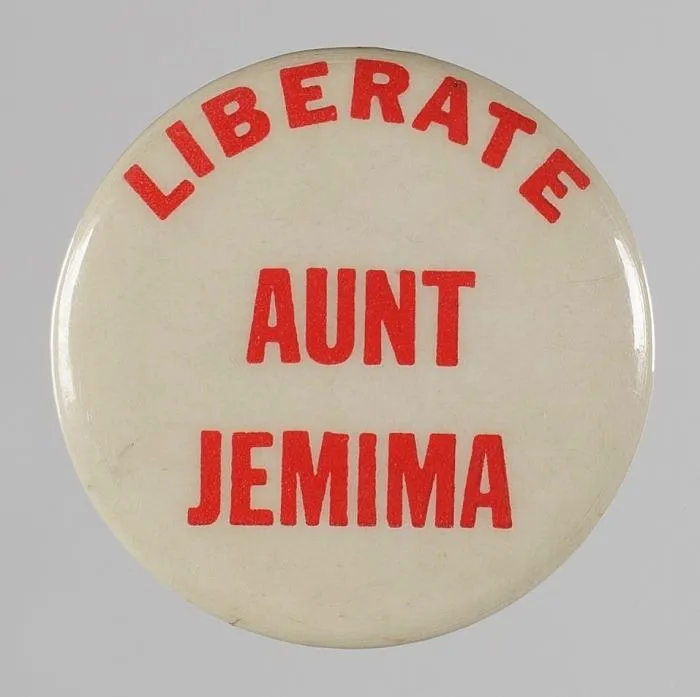

Criticism of Aunt Jemima as a “stereotypical trope of black womanhood” is nothing new, adds Strait. In one of her most iconic works, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), artist Betye Saar depicts an Aunt Jemima figurine holding a broom in one hand and a rifle in the other, transforming her “docile image … [into] a rifle-carrying warrior that symbolically frees the character by challenging and confronting the inherent violence of racist imagery and pejorative stereotypes,” according to the curator. (The National Museum of African American History and Culture houses a pin inspired by Saar’s artwork in its collections.)

“I used the derogatory image to empower the black woman by making her a revolutionary, like she was rebelling against her past enslavement,” wrote Saar in a 2016 essay for Frieze. “When my work was included in the exhibition ‘WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution’ at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 2007, the activist and academic Angela Davis gave a talk in which she said the black women’s movement started with my work The Liberation of Aunt Jemima. That was a real thrill.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)