Tracking Fishing Vessels Reveals Industry’s Toll on the Ocean

Satellites and artificial intelligence fill in gaps in global fisheries knowledge

Fishing feeds many of the world's 7.6 billion people. But our hunger for sea life has a toll—something not always easy to grasp thanks to the vastness of the oceans and diversity of fisheries. Now, a high-tech collaboration brings the startling range of our impact to light. As Dan Charles reports for NPR, a new study suggests fishing activity covers at least 55 percent of the the planet's oceans.

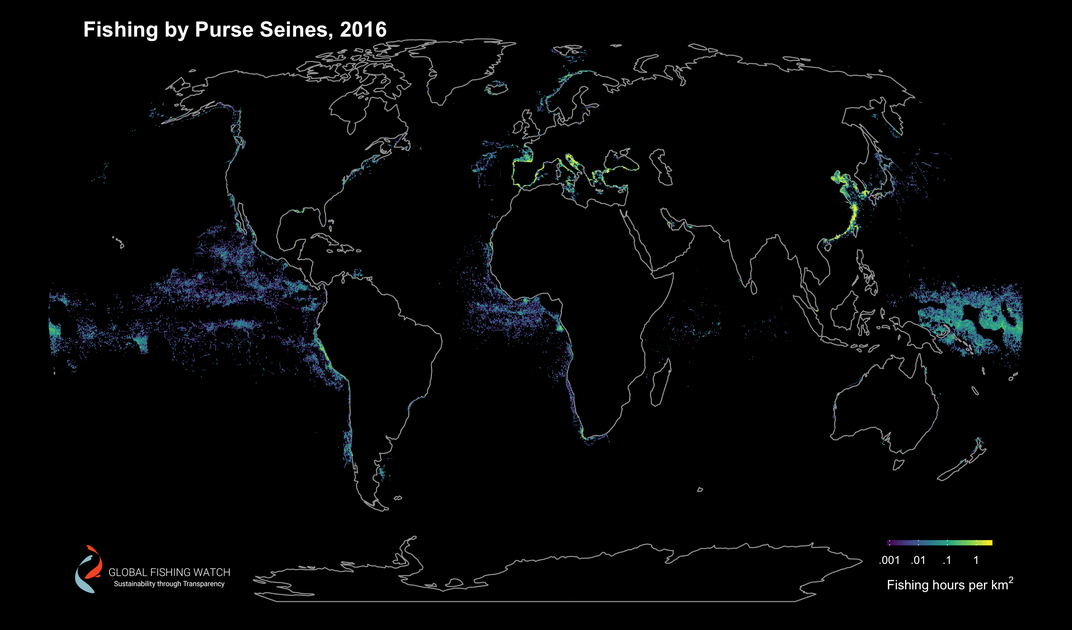

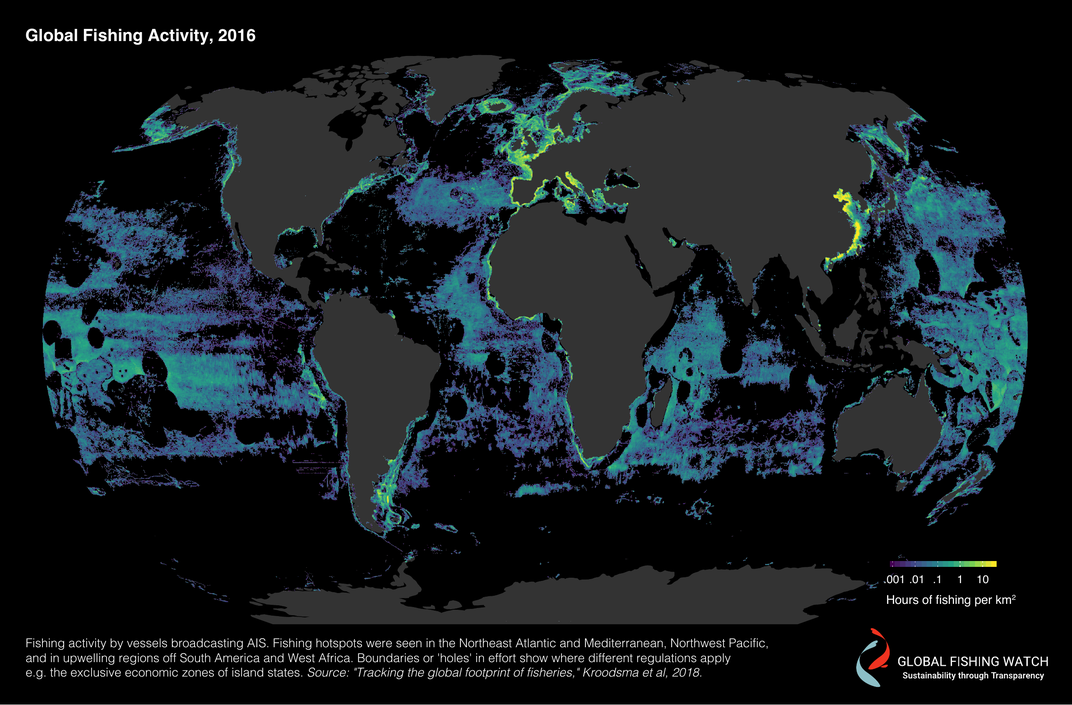

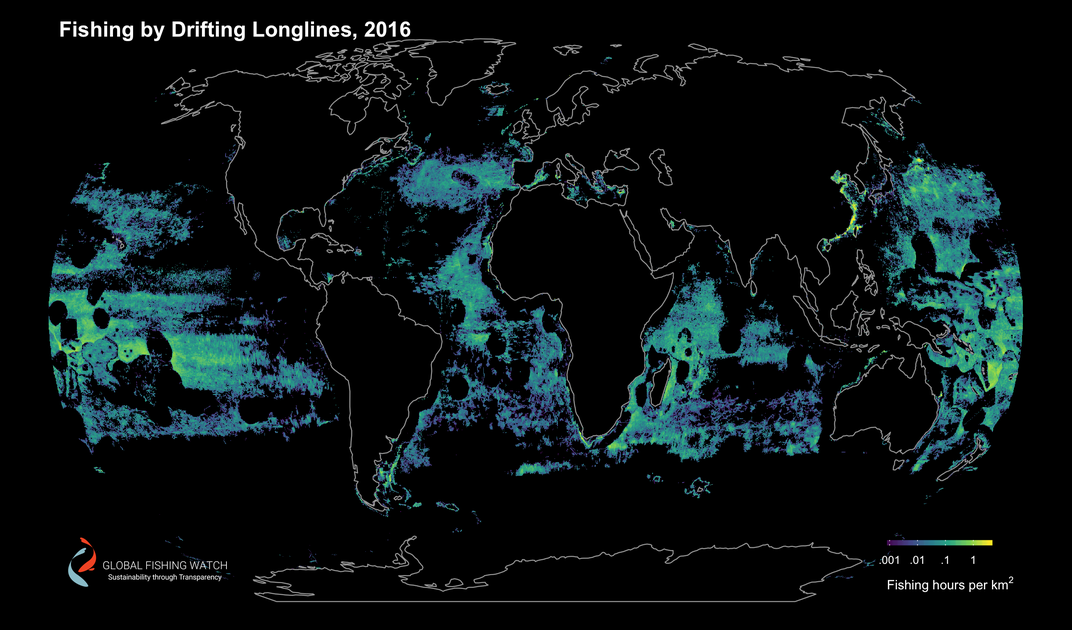

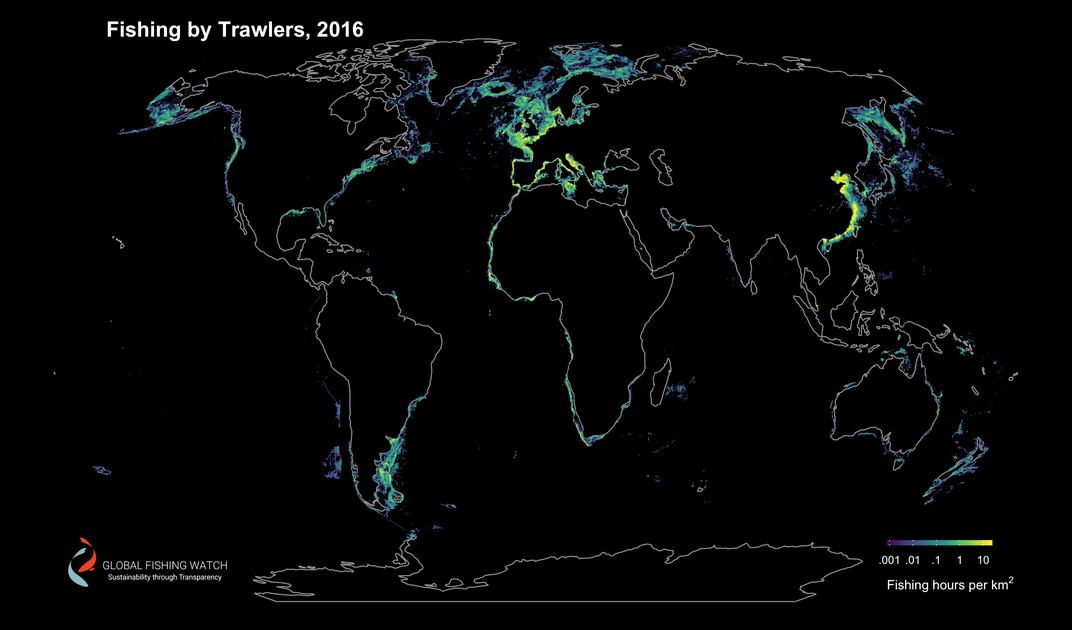

The study, published in Science, uses several maps to detail where fishing vessels go, when they fish and how. The scientists explain that past fishing surveys have relied on data collected in logbooks, by observers at fishing ports and electronic vessel tracking. But that hodgepodge of methods fails to capture a complete, global picture of fishing. This time, the researchers turned to more impartial, distant observers: satellites.

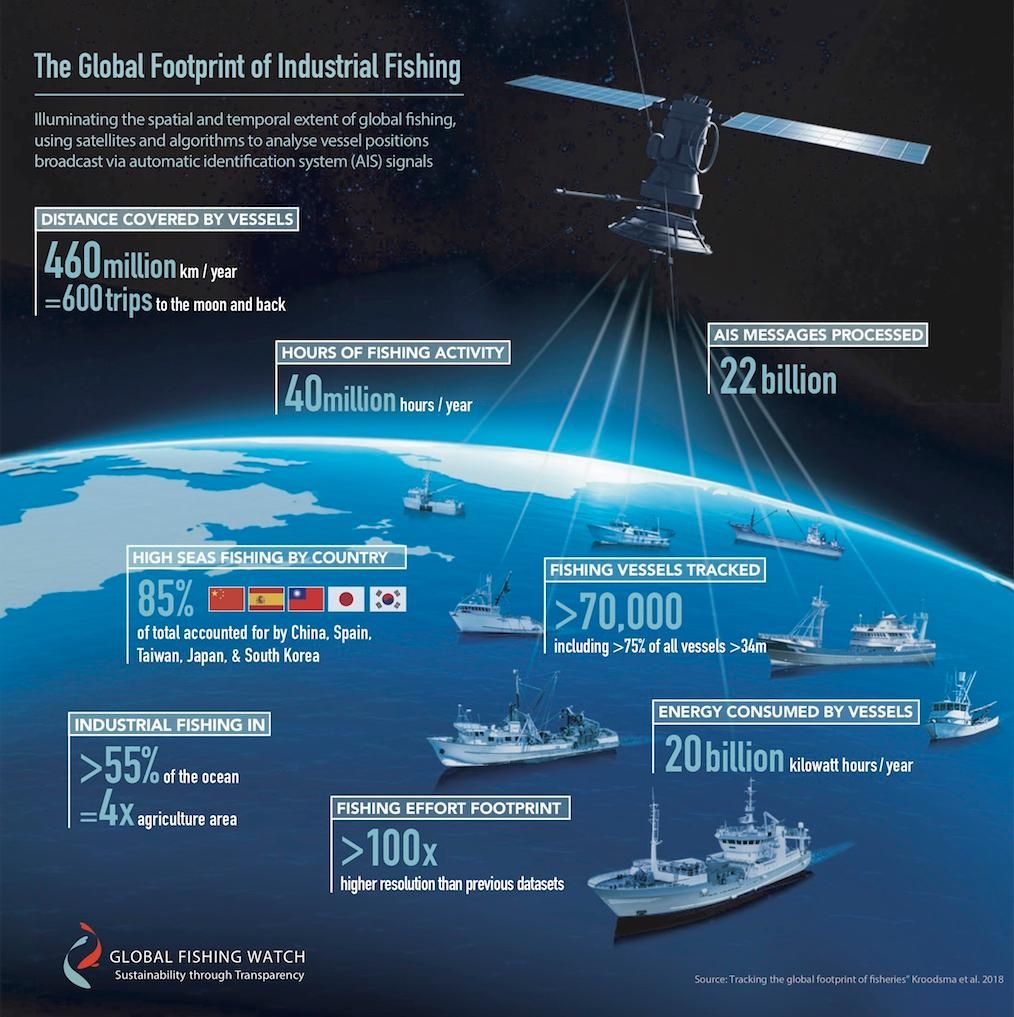

Recently, an increasing number of fishing vessels are required to carry an automatic identification system (AIS), originally meant to prevent ship collisions. The AIS sends data about the ship's location, identity, speed and turning angle to satellite and land-based receivers. The scientists were able to use that data in their work. Dubbed the Global Fishing Watch, the effort unites scientists from several institutions and universities as well as a remote sensing company called SkyTruth, based in Shepherdstown, West Virginia.

The effort "provides a stunning illustration of the vast scope of exploitation of the ocean," says SkyTruth's president, John Amos, in a press release. "Now that we can observe and directly measure fishing effort, governments, fishers, the seafood industry and consumers have new tools to manage these important resources, and a strong foundation to build toward sustainability.”

The team took 22 billion AIS positions collected between 2012 to 2016 and fed that data into two neural networks — computer algorithms that learn and look for patterns in large data sets. One matched vessels to official fleet registries to come up with the type of vessel, size and other identification information. The other looked at vessel tracks to figure out when the vessel was fishing and how.

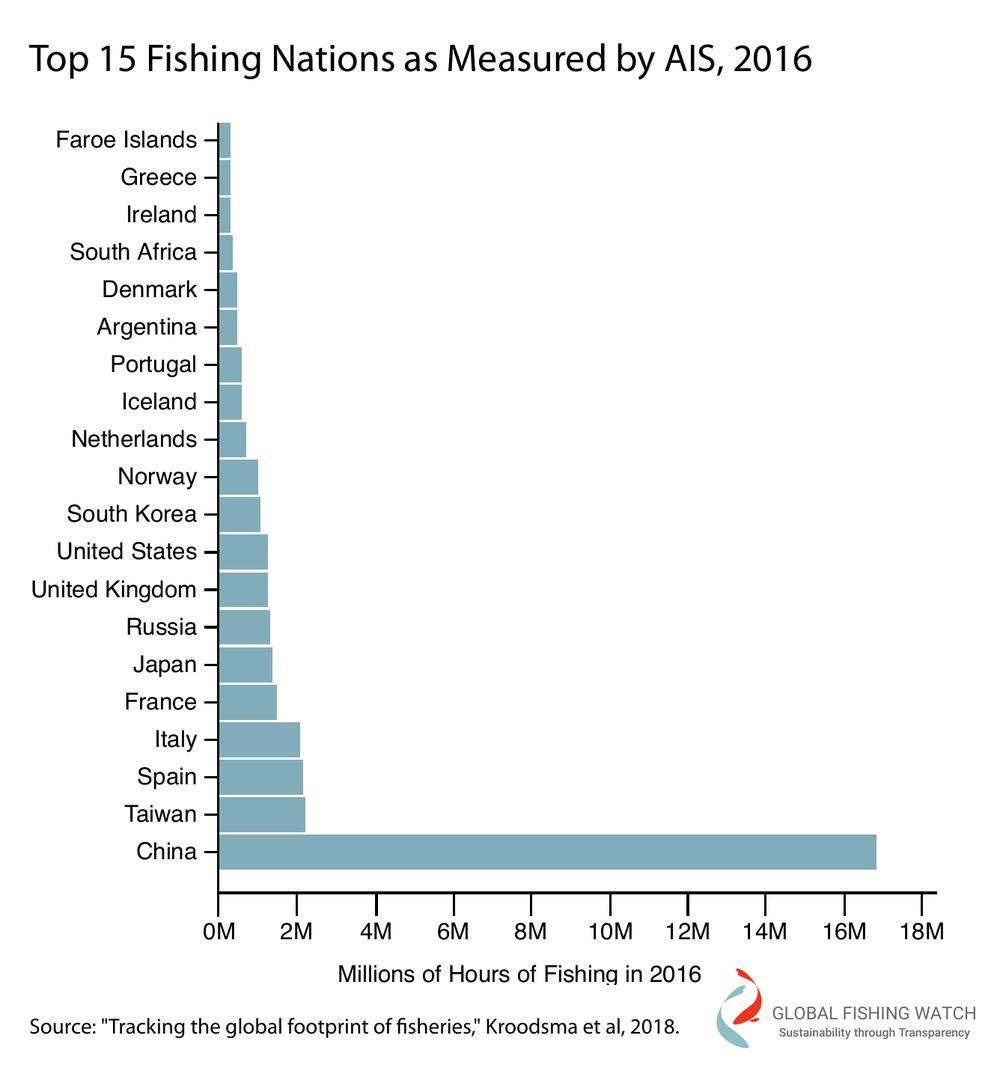

In 2016 alone, the data set included more than 40 million hours of fishing. The tracked vessels consumed 19 billion kilowatt hours of energy (one kilowatt hour is roughly equal to the electricity needed to power the average microwave for an hour, according to a video from Ontario government services.) The ships traveled more than 460 million kilometers—a distance equivalent to traveling to the Moon and back 600 times.

The vessels captured represent just a portion of fishing boats on the seas, but it is enough to give the researchers a clearer picture of global fishery activity.

Most fishing happens near coastlines, where countries tend to stick within their own economic zones, but there are hot spots in open ocean, writes Carolyn Gramling for Science News. Those spots include the northeastern Atlantic and spots off the coasts of South America and West Africa where nutrient-rich waters well up from deeper waters. As Gramling writes, just five countries — China, Spain, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea — are responsible for more than 85 percent of fishing that happens on the high seas, outside of their own economic zones.

“The results are remarkably consistent with the catch data that have been traditionally employed to measure fishing effort,” Jeremy Jackson, a marine sciences expert at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, tells reporters Chris Mooney and Brady Dennis for The Washington Post. “Ditto the fact that China, Spain, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea take 85 percent of it all on the high seas. Still, it’s good to see the strong confirmation, and of course it’s unsustainable without massive restrictions in effort.”

The completeness of the data could be improved if the results can help pressure the International Maritime Organization to require even small fishing vessels to be satellite-monitored, Daniel Pauly a fisheries expert at the University of British Columbia tells The Post.

Already the study offers a clearer large-scale picture of fishing than past efforts. With information, experts have the tools to see problems with overfishing and more importantly, the solutions.