Why the Humble Sweet Potato Won the World Food Prize

Researchers are helping to fight malnutrion and childhood blindness in Africa with new varieties of starchy, orange-fleshed sweet potatoes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/d4/b7d43493-3ce5-439a-8b57-70f29f71b6b1/5183843480_478eee5564_b.jpg)

Most Americans are familiar with orange sweet potatoes—as slivers fried in oil or cubes smothered in cinnamon and sugar, possibly topped with marshmallows. But there's a whole tuber rainbow commonly eaten elsewhere in the world, including white, yellow and even purple varieties.

In parts of Africa, the firm-fleshed white or yellow sweet potatoes are a daily staple. And although the tasty tubers are fairly nutritious, a group of food scientists set out to engineer something better. This week their tireless efforts earned these scientists the 2016 World Food Prize, reports Tracie McMillan for National Geographic.

The $250,000 prize is awarded each year to individuals or groups who improve the “quality, quantity or availability of food in the world.” This year’s laureates include Maria Andrade, Robert Mwanga and Jan Low of the International Potato Center and Howarth Bouis whose research organization Harvest Plus works on “biofortification” of crops.

Traders introduced the sweet potato to Africa in the 1600s, and the locals chose the starchier white potatoes over the mushy orange ones. But the starch came at a cost. While the orange variety is full of vitamins and nutrients, the pale varieties are nutrient poor—and over time the people suffered greatly from malnutrition.

But research recently showed that just one capsule of vitamin A every six months could cut child mortality by 25 percent, reports Dan Charles at NPR. Up to half a million children go blind each year because of vitamin A deficiency, and six percent of deaths under the age of five are caused by lack of the nutrient.

“This number really astounded the nutrition community,” Bouis tells Charles. “Then they started looking at iron and zinc and iodine deficiencies.”

Even so, getting vitamin capsules to millions of people in remote villages is a pricey and difficult endeavor. But Bouis reasoned that if researchers could breed crop varieties that naturally produce those nutrients, they could provide steady access to vitamins and other micronutrients. “Once that seed, that variety, is in the food system, it’s available year after year after year,” he tells Charles.

After several other attempts, the researchers turned to one of the area's major food staples: the sweet potato. If they could get populations to switch to the orange-fleshed varieties, they believed that they could combat some of those health challenges. But the problem was in the texture.

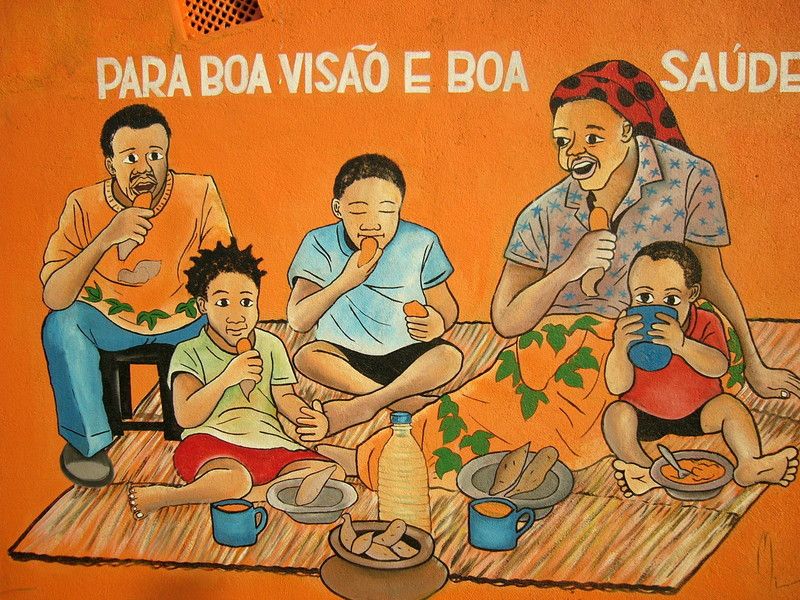

The people in Africa were used to the firm white or yellow sweet potatoes—the mushy orange potatoes just wouldn't fly. So, the research team began breeding starchier varieties of orange sweet potatoes that still contained high amounts of nutrients including beta carotene, which the body uses to make vitamin A.

The last hurdle, however, was getting people to adopt the new crop. Maria Andrade, one of the team members and a plant geneticist from Cape Verde, began introducing the crops in Mozambique and Uganda in 1997.

She created a marketing campaign for the potatoes, including radio advertisements and visits to villages in her bright orange Land Cruiser with sweet potatoes painted on the side. According to Charles, she taught children songs about the potato's nutrition, put on skits about it and helped develop recipes for the potato. Potato advocates also helped farmers create small businesses selling cuttings of the vines.

And the campaign is working.

Two million households in ten African countries either consume or grow the orange sweet potatoes now, McMillan reports. At markets, sellers often cut off the tip of the potato to show the orange flesh inside, which has become a selling point.