Finding Lessons on Culture and Conservation at the End of the Road in Kauai

In the remote, tropical paradise called Ha‘ena, the community is reasserting Native Hawaiian stewardship of the land and sea

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/79/b4/79b42fb9-3ec7-4305-bb17-2c964a96960f/unspecified_2.jpg)

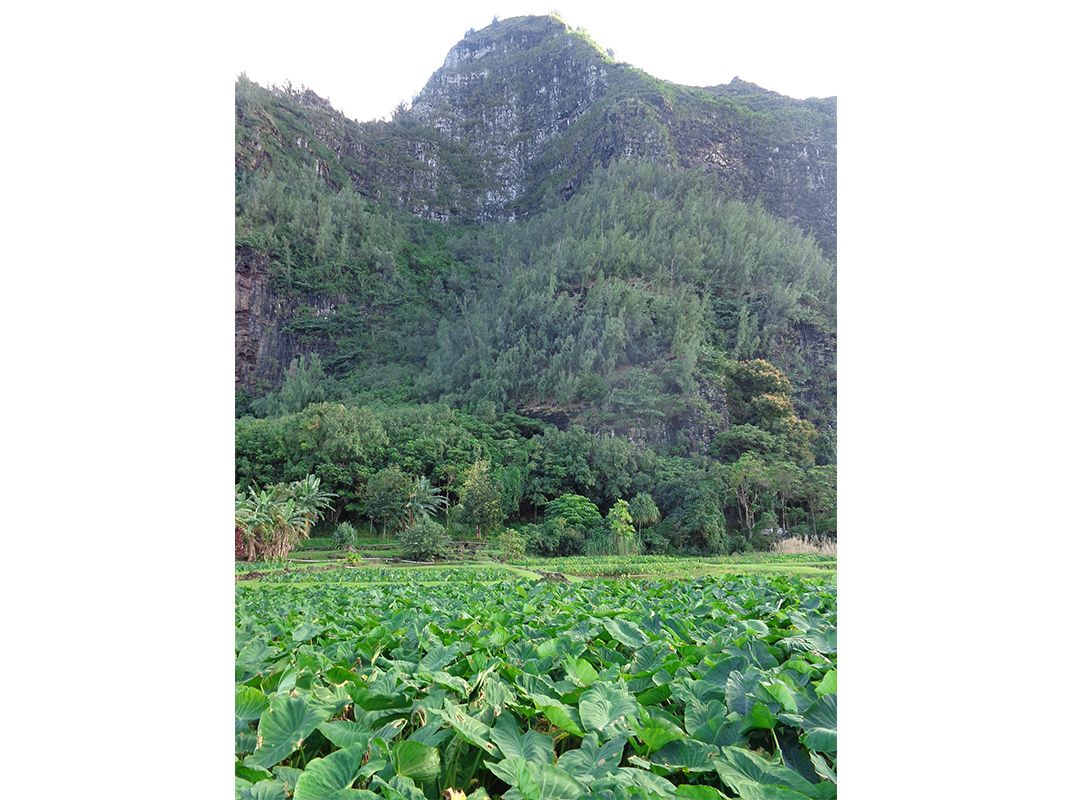

Our feet squish in the mud of the taro patch and water is halfway up to our knees. Around us the heart-shaped leaves of the gorgeous plants swirl with a rich green that looks more like it belongs in an oil painting. The sun rises, casting a morning light against the great pyramid shape of Makana mountain above us.

We are pulling weeds in the recently restored taro pond fields, called loʻi, that are now tended by the Hui Maka‘ainana o Makana, a non-profit group comprised of the Native Hawaiians, descendants of those who once resided in this land known as Ha‘ena, and a group of their supporters. “We define community as ‘whoever shows up to do the work,’” explains one of our hosts.

Here at the end of the road on the island of Kaua‘i—as in many other small places around the islands—the community is reasserting Hawaiian stewardship of the land and sea.

I first came to work here in 2000, researching for a start-up project called “Pacific Worlds.” The idea, based on the “Geografía Indígena” (Indigenous Geography) project I had worked on at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian a year before, was to create community profiles of place-based indigenous cultural heritage, in which all the content came from members of the community.

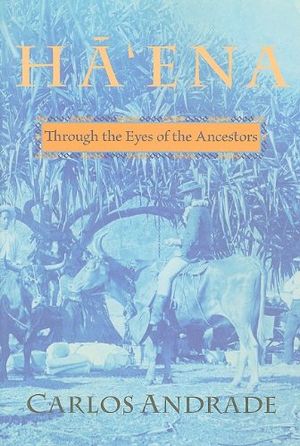

I had a tiny seed grant from the Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities, and with my Native Hawaiian colleague Carlos Andrade, we did a handful of interviews that produced my first such profile. The project itself was web-based, and was accompanied by curriculum for teaching Pacific Island cultures from Pacific-Islander points of view. Now here I am, 16 years later, back to redo that project on a larger scale.

“In the mid-'60s the state condemned the land, evicted all the families, and then did very little except to make a couple of small parking areas and limited “comfort station” for visitors,” recounts Andrade. Born and raised on the island, Andrade spent many years working, living, and raising his family in Hāʻena. His book, Hāʻena, Through the Eyes of the Ancestors, is based on his life experiences there. “Consequently,” he says, “without any real commitment of labor to take care of the area’s resources, what was once an area of homes and cultivated pond fields of taro became a dumping ground and jungle of trees and shrubs, all invasive species.”

The descendants of Hāʻena families and their supporters grew tired of the government’s inability to care for the place, he says. The area was once sacred to their ancestors and it was filled with storied places of gods and the Hawaiian people. Ha‘ena is also one of the most famous centers for the art of hula dance and music.

“So we set about to find a way to intervene,” says Andrade.

Hāʻena is a special place. Except for the privately owned island of Ni‘ihau, Kaua‘i is the most geographically remote of the main Hawaiian islands; and Hāʻena is literally at the end of the road on the island’s lush north shore. It lies about 7 miles past the town of Hanalei, made famous for its mispronounced appearance in the song “Puff the Magic Dragon.” The beauty is so spectacular that scenes in the movies South Pacific and Jurassic Park were filmed in this area. If you want remote tropical paradise, this is the place.

But we are here for a different reason: to document the efforts at restoration—both environmental and cultural—that are taking place on these gorgeous tracts.

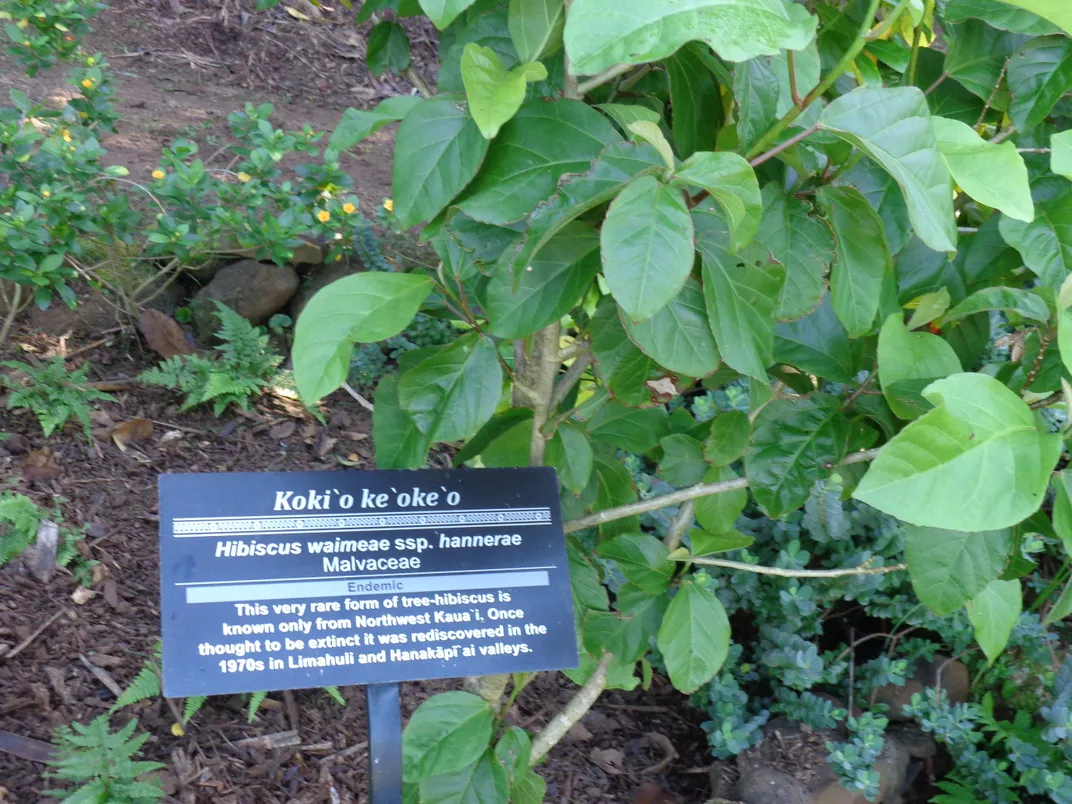

As the most remote landfall on Earth, the Hawaiian Islands are replete with unique species. The few plants and animals that managed to make it out here spread out and diversified into multitudinous new species to take advantage of diverse ecological niches.

“The vast majority—90 percent—of the plant species in Hawai‘i are endemic,” says Vicki Funk, senior research botanist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. “They may have cousins elsewhere, but the Hawaiian species are unique.” Since Captain Cook put the islands on the map in 1778, introduced species have wreaked havoc on the less aggressive native flora and fauna.

The onslaught has been devastating. As the Hawaii State Division of Forests and Wildlife states: “Today Hawaiʻi is often referred to as the ‘Endangered Species Capital of the World.’ More than one hundred plant taxa have already gone extinct, and over 200 are considered to have 50 or fewer individuals remaining in the wild. Officially, 366 of the Hawaiian plant taxa are listed as Endangered or Threatened by Federal and State governments, and an additional 48 species are Proposed as Endangered.” While only comprising less than one percent of the United States land mass, Hawaiʻi contains 44 percent of the nation’s Endangered and Threatened plant species.”

The unique birdlife has also been devastated. “Before human arrival in Hawaii, I estimate there were at least 107 endemic species of birds living in the islands,” says Helen James, also from the Natural History Museum and a world expert on Hawaiian birds. “Only 55 of those species were found alive in the 1800s. By the end of 2004, only 31 endemic species still survived. Today, there are very few endemic Hawaiian birds that are not considered threatened or endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.”

The Native Hawaiian way of life has been devastated. Statistically, they are among the most challenged “minorities,” and in their own homeland. Many are afflicted by chronic health problems. They make up a high percentage of the prison population, and appear in the lower rungs of educational, economic and other statistics, indicating a population under stress.

Enlightened Hawaiian chiefs as far back as the 14th century instituted what is called the moku-ahupua‘a system of management throughout the islands. The concept is simple: divide each island like a pie into big sections running from the mountaintops to the sea, then subdivide each of those into smaller slices. The bigger sections, called moku, are intended to be self-sustaining in natural resources. Most everything one could need should be available there. Then the smaller slices, or ahupua‘a (AH-hoo-poo-AH-ah) are administrative divisions within the moku. All of these were administered by the ali‘i, the traditional leaders of their society.

In traditional Hawai‘i, each ahupua‘a would have a land manager, or konohiki, appointed by the chief to ensure the fruitfulness of the land. The konohiki had to know what was in the forest, where the best agricultural lands were, and what was going on in the sea, for the ahupua‘a extended out to the edge of the reef (or, if there was no reef, a certain distance out into the sea).

When certain species became scarce, or during spawning seasons, the konohiki would place a kapu (taboo) on harvesting, to ensure that the species regenerated. Fruitfulness is not a one-time thing, after all, but requires sustainable practices. The konohiki also ensured that the maka‘ainana—the people of the land—were cared for.

Recognition was accorded to them for their skills, and the resources were managed effectively for all who lived on the land. Thus when the paramount chief and his representatives made their yearly circuit of the island, offerings for continued peace and prosperity as well as gifts to honor the elevated genealogies would be placed on the pig’s-head altar (ahu pua‘a) that marked the boundary of each of these land divisions. If the bounty was deemed not sufficient, it indicated that the management of that ahupua‘a was not up to par, and a shakeup of governance would ensue.

All that changed starting in 1848 when King Kamehameha III, under incredible pressure from outsiders, divided the land of the kingdom and created private property.

This move is known as the 1848 Mahele (“division). For the average Hawaiians, this mostly meant they lost much or all of their lands. The clash of two systems was incomprehensible, the surveying techniques rudimentary, and the culture shock enormous.

Sugar plantations blanketed the islands and eradicated much of the landscape Hawaiians had known for centuries. Under U.S. law since 1900, the traditional ahupuaʻa fisheries were condemned and opened to the general public and the traditional place-based management regimes discarded and replaced by central government controls essentially leading to a classic “tragedy of the commons,” where self-interest trumped the common good.

But here in Ha‘ena, something very different took place. The people formed a group (hui) and managed the land collectively. In 1858, the chief who owned the ahupua‘a, Abner Paki, deeded his land to a surveyor, who later deeded it to William Kinney. In 1875, Kinney was approached by a group of Ha‘ena residents seeking to establish a collective landholding arrangement that would keep the remainder of the ahupua‘a intact and in use by the community. Consequently, Kinney deeded the land to "Kenoi D. Kaukaha and thirty-eight others." These people formed an organization called the Hui Ku‘ai ‘Aina—“the group that bought the land.”

The Hui allowed for a more traditional land-holding relationship in which shareholders owned the land in common. Interests were undivided unless agreed upon by the shareholders who were able to identify their own house lots and cultivated grounds. Each shareholder could graze designated animals and gather from the other resources on the common lands. This was much more in keeping with traditional Hawaiian land tenure than the privatized system spurred on by the Mahele.

But over the next century, changes that were affecting the rest of the Hawaiian Islands gradually reached Ha‘ena—wealthy individuals—non-Hawaiians, who had purchased shares in the Hui—successfully sued the remaining shareholders, resulting in the partitioning of the lands that had once been held in common. After Statehood in 1959, the Hawaii state government created a state park at Ha‘ena, evicting all of the remaining Hawaiian residents from their homes and farmlands. A group of young people from the mainland, and part of the “flower power” movement, built and occupied what became known as “Taylor Camp,” leaving the productive and well tended taro lands of Ha‘ena to become an overgrown forest of invasive trees, shrubs, abandoned automobiles, and other detritus.

But over the past few decades, three major changes have taken place—the most recent being in the past year. First is forest conservation: the Wichman family, who came to own almost the entire valley portion of Ha‘ena, turned it into Limahuli Gardens, now part of the National Tropical Botanical Gardens. The land is in conservation, and the staff is working against the onslaught of invasive species.

Limahuli Gardens’ director, Kawika Winter, points out three restoration scenarios they are trying to implement: “The first is ‘pre-rat,’” he says. “We now know that introduced rats, not humans, were the major drivers in the change of forest structure and composition. Forests went from being dominated with large-seeded species dispersed, by flightless birds, to smaller-seeded species that rats do not eat or prefer.

“Second we call ‘20th-Century Optimal,’” says Kawika. “This is the crumbling forest community that was witnessed by 20th-century botanists, and mistakenly labeled as ‘pristine.’ Both of these are the aims of many conservationists, but they are impractical and financially unsustainable for us to restore.”

“Third we call ‘future resilient.’ This is a native-dominant forest of a structure and composition that may have never before existed, but is most likely to survive the onslaught of invasive species and global climate change.” He adds, “We are working towards each of these scenarios, the first two on a small scale, and the last one on a more large-scale.”

The second initiative is manifesting on the kula—the gently-slooping agricultural land between the mouth of the valley and the seashore. Here a group of mostly former residents, who had farmed the fertile lands between the valley and sea, approached the State regarding the semi-abandoned State Park.

“A few of us sat around the table in Grandma Juliet’s house,” recalls Makaala Kaaumoana, “and we decided that we would form Hui Maka‘āinana o Makana as a non-profit. And the ultimate purpose was for the families of Ha‘ena to take care of that place.” The Hui Maka‘āinana o Makana—“People of Makana Mountain”—is a 501(c)3 non-profit, the mission of which is to work in the park, to improve the recreational and cultural resources there, “and most importantly, at least from our perspective, to fulfill our traditional responsibility to care for our elder sibling, the ʻāina (land),” says Andrade.

“After building trust by assisting state park archeologists in documenting significant resources, and working with state personnel to get much needed work done, the Hui entered into a curatorship agreement with the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) State Parks division, whereby we are able to augment the efforts of that agency to fulfill its mission,” Andrade says, “and we are also able to fulfill our kuleana (responsibility) to our ancestors.”

Taro (or kalo), the staple food of Hawaiians, grows in terraced pond fields similar in construction to rice paddies. The steamed starchy corm was pounded with water into a creamy paste called poi.

Poi and the cooked green leaves, stalks and flowers of the taro was central to most traditional Hawaiian meals. And in the time since the Hui was founded, more than two acres of taro fields have been cleared of forest and restored to production and now present a beautiful and well-tended landscape.

“We could sustain ourselves throughout our whole life,” recalls Kelii Alapai, who grew up in Ha‘ena. “Anything happens, we don’t need to worry—hey, we did it. Before, we had only two stores. We never had Foodland, Safeway—we never needed all that. We raised our own beef, we raised our own poultry, and we raised our own pork. We got our poi, we had our fish in the ocean. We had our limu (seaweed) in the ocean. So, simple life, man, simple life.”

But finally overexploitation started to affect the fishing grounds of Ha‘ena, spurring the last and most recent initiative: The Ha‘ena Community Based Subsistence Fishing Management Area. The first of its kind in the Hawaiian Islands, if not in the U.S.A., this area offshore of Ha‘ena is designated for subsistence fishing only—no commercial fishing. And the rules for subsistence fishing are based on the traditions passed down by the elders.

“It was the dream and the vision of several of the kupuna (elders) from Ha‘ena,” says Presley Wann, head of the Hui Maka‘ainana o Makana. “They had the vision. They felt that it was starting to get overfished and they wanted to pass on to the next generation the same area that fed us so well.”

The traditional code is simple: take only what you need.

But it also involves knowing the spawning and growth cycles of the different fish. “Uhu (a type of parrotfish that can change its sex) is a fish that our divers love to catch, they love to show off the fact that they have an uhu,” notes Makaala. “And I explained to them that if you caught the blue uhu, then they can’t have any babies until one of the red (female) uhu turns into a blue uhu and becomes the male. It just takes time.”

“Why do they come to fish in Ha‘ena?” Alapai asks. “Because we have fish. And why do we have fish? Because we take care of fishing. So now let everybody see what we’re doing with our fishing boats. Hopefully they can pass the word on to their community, where they come from. Anybody can come fish at Ha‘ena, but when you guys come fish in Ha‘ena, you just got to follow our rules, respect our place. Simple, and then that’s how it was back then, simple. You take what you need, that’s all.”

Education about the rules is extended to the broader community by the members of the Hui and other volunteers from the Hāʻena community. Enforcement comes through a solid relationship with the DLNR. “Makai (beach) Watch is basically you have no enforcement powers,” Presley explains. “It’s like a neighborhood watch. And it trains the community, people are involved and want to be a volunteer. They’re taught how to approach people that are behaving inappropriately.”

“It teaches them non-confrontational communication skills to assist in caring for ocean resources,” Andrade adds. “And, if rule-breakers aren’t responsive, watchers are taught the proper way to document irresponsible activities to assist enforcement personnel in their efforts to adjudicate the offenders.”

“I’d like to see it where we wouldn’t have to have much enforcement,” Presley continues. “It would work on its own and everybody would be on the honor system. Deterrence is key: once the word gets out that people are going to be watching, you’d better not do anything stupid down there, just follow the rules, right? So ideally that would be the situation in 20 or 30 years.”

All of this is part of the larger trend of conservation biology that the U.S. Forest Service is exploring. “Conservation biology is continually evolving—from protecting nature for nature’s sake to today supporting socio-ecological systems,” says Christian Giardina, research ecologist for the U.S. Forest Service’s Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry, who is funding our research. “It’s moved from focusing on biodiversity and protected-areas management, to focusing on natural-human systems, and managing for landscape-scale resilience and adaptability.”

“It is logical then that natural resources professionals would turn to indigenous cultures for guidance and collaboration, as these cultures have focused on socio-ecological systems for millennia,” Giardina says. “Here in Hawai‘i, Native Hawaiian communities are leading a transformation in how conservation views and interacts with the natural world. For the USDA Forest Service’s Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry, being a part of this transformation is essential to being an effective land-management focused organization today and into the future. We are embracing this change by immersing ourselves in partnerships that operate from this bio-cultural foundation.”

In the busy rush of contemporary life, it takes commitment and hard work to care for the ʻāina. In a community where homes now sell for multi-millions of dollars, most descendants of the original Hāʻena Native Hawaiian families no longer can afford to reside there due to skyrocketing land prices and extremely high property taxes.

Subsequently, many have moved to less expensive parts of the island and but still commute back to plant and fish. “We hear the name ‘community’ all the time,” points out Andrade. “Who is the community? We have Native Hawaiians, we also have people descended from the immigrant workers that lived here. We now have people who are absentee landlords, we have movie stars’ and rock stars who own lands in Ha‘ena. We have transient people, just in and out for vacations, and people just driving through—there are literally thousands of them every day. And so who is the community? We, the ones who clear the invasives, restore the taro fields to production, maintain the ancient water systems and do the daily and weekly work of maintenance of this ʻāina feel that the community are the people that show up on work day, and do the work that needs to be done. That’s the community.”

Here at the end of the road at the end of the Hawaiian Islands, such an integrated approach to integrating environmental management and traditional culture is setting a model for the rest of us.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Doug-BPBM-2011.jpg)