Sweet! You Can Now Cook the Food From the African-American History Museum’s Award-Winning Café in Your Own Home

Smithsonian Books introduces the Sweet Home Café Cookbook, chock full of delicious riffs on classic African-American recipes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/98/e2/98e2fa30-8711-4a10-8453-5704d2b530ee/sweethome_0290.jpg)

Editor's note, March 28, 2019: Congratulations to Smithsonian Books for being nominated for the highly coveted James Beard Foundation Book Awards.

From the artful ascending layout of its exhibitions to the assertive beauty of its architecture, the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. offers many enticements to visitors. One essential aspect of the museum experience that may be less apparent to first-time guests, however, is the Sweet Home Café, the museum’s in-house cafeteria.

A far cry from your typical mess hall, the Sweet Home Café offers a large menu of complex dishes intimately connected with the African-American experience. Helmed by Maryland-born executive chef Jerome Grant, the Café categorizes its diverse, but invariably hearty, meals by region of origin: Agricultural South, Creole Coast, Northern States or Western Range.

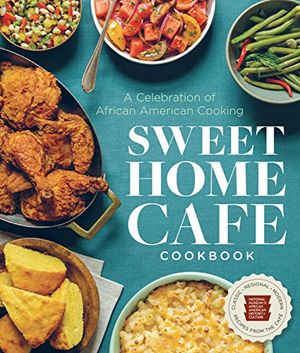

These regions are likewise a roadmap of the just-released Sweet Home Café Cookbook from Smithsonian Books, which graciously ushers the mouthwatering entrees, desserts and sides of the Café directly into the homes of readers.

The agricultural south, once the nexus of plantation slavery, was the site of wide-ranging African-American culinary innovation from colonial times onward. Scant resources and brutal circumstances meant that a spirit of creativity was required to survive. Pioneering black cooks like Hercules, George Washington’s enslaved personal chef, or George Washington Carver, who ideated scores of novel uses for the peanut, helped lay the groundwork for a gourmet legacy.

In the Café Cookbook, Smithsonian chefs showcase updated takes on southern classics including chicken livers and grits (an evergreen example of culinary resourcefulness), fried okra (complemented by a dip of rich pimento cheese aioli), buttermilk fried chicken (a favorite at the museum), crackling cornbread (named for the pork rinds that impart a husky flavor to the product), and the tried-and-true New Year’s concoction known as Hoppin’ John (whose defining ingredients are black-eyed peas and rice).

Sweet Home Café Cookbook: A Celebration of African American Cooking

The National Museum of African American History and Culture's Sweet Home Café showcases the rich culture and history of the African-American people with traditional, authentic offerings as well as up-to-date dishes. The award-winning culinary historian Jessica B. Harris served as advisor to the museum as it developed the café. Chef Albert Lukas crafted the innovative and highly acclaimed café menu, which ties together food history, heritage ingredient sourcing and modern tastes. Executive Chef Jerome Grant develops inventive special meals for holiday celebrations.

The flavors of the Creole coast, a sizable stretch of territory rimming the Gulf of Mexico, diverge significantly from those of the southern staples above, largely due to the region’s confluence of disparate immigrant cultures. “Local foodways mixed and mingled with those of Europe, Africa and the Caribbean,” write coauthors Albert Lukas and Jessica B. Harris, “as well as with those of Native Americans through extended contacts within the Atlantic world.”

Creole selections from the cookbook include pickled Gulf shrimp (seasoned with allspice berries and celery seeds), Frogmore stew (a boiled blend of shrimp, crab, kielbasa sausage and corncobs), a catfish po’boy sandwich (the pride of New Orleans, served on a “French-style loaf”), and, for dessert, a filling rum raisin cake (whose molasses flavoring gestures to the region’s deep history of sugarcane cultivation).

Many tend to think of African-American cooking as strictly southern, but black chefs exerted ample culinary influence in New England and environs as well. The northern states region of the Sweet Home Café Cookbook—“which includes not only the ‘mythic’ north of the enslaved but also the north of the Great Migration”—was a hotbed of African-American experimentation with seafood recipes. The text notes that black northerners in early America would often leverage their culinary chops to climb the social ladder, as Rhode Island oyster and alehouse entrepreneur Emmanuel “Manna” Bernoon did upon his emancipation in 1736.

Connoisseurs of northern fare can look forward to sampling the book’s interpretations of pan-roasted oysters (blanketed by a piquant chili cream sauce), oxtail pepper pot stew (a Guyanese Christmas dish featuring cassava root syrup and flaming-hot wiri wiri peppers), Maryland crab cakes (fried and bearing traces of Dijon mustard, Old Bay, Worcestershire sauce and Tabasco) and their cod cake cousins (served with gribiche, a French twist on tartar sauce).

The featured region that may be most surprising to readers is the western range, but the authors of the Sweet Home Café Cookbook note that enterprising African-Americans who pushed westward in the age of conestoga wagons regularly devised rugged but tasty recipes on the fly. They also brought with them meals from their birthplaces, as was the case with ex-slave Abby Fisher, a postbellum migrant who established herself in San Francisco. Fisher built from the ground up a robust catering and pickle business, and penned a seminal African-American cooking text, What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Old Southern Cooking.

The Café Cookbook’s nods to the old west include a barbecued brisket sandwich (“In much of the South, barbecue is about pork. In Texas, however, beef brisket is the chosen meat on the barbecue trail.”), pan-roasted rainbow trout (glazed with hazelnuts and brown butter), empanadas (stuffed with black-eyed peas and chanterelle mushrooms in a cross-cultural twist), and cowboy campfire-appropriate son-of-a-gun stew (replete with onions, turnips, corn kernels and abundant short rib meat).

The selections from the four featured regions are complemented by a handful of dishes served exclusively at the African American History museum, ranging from curried goat and jerk chicken preparations playing on Jamaican traditions to a collard, tomato and cashew stew in which cardamom, curry powder and coconut milk put an Asian spin on African-American eating.

And if you’re struggling to liven up Thanksgiving this year, look no further than the Sweet Home Café Cookbook’s reinventions of Big Easy grillades (gravy-bathed turkey medallions garnished with fried apple wedges), candied sweet potatoes (“This version has so much taste that you won’t even miss the marshmallows.”), and peach and blackberry cobbler (paired with cold vanilla ice cream). All are guaranteed to content at least six quarrelsome relatives.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)