Jacques Pépin Donates a Hand-Painted Menu From His Last Supper With Julia Child

This month the modern traditionalist chef is honored with the first-ever Julia Child Award

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/47/50/4750f30a-455e-48bf-9f4e-57443610ae53/jp-illustratedmenujc-houseoct-292001web.jpg)

The food world these days often seems as crazily polarized as so much else in our lives: You’re either a no-gluten, anti-carb, sustainable-everything consumer of cage-free eggs and nitrate-free bacon or else you’re a devotee of the drive-through lane, the freezer case and the Crock-Pot.

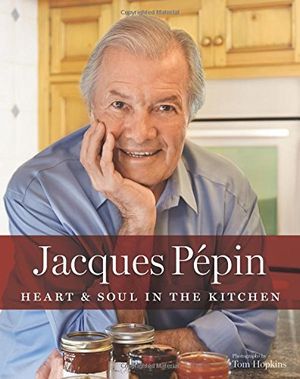

Although it can seem hard to find a middle ground, cooks and eaters everywhere can find an island of sanity in the person of master chef Jacques Pépin, who this year celebrates his 80th birthday with the publication of a new cookbook, Heart & Soul in the Kitchen.

Pépin has cooked, tasted and nibbled his way through more than two dozen cookbooks and innumerable television shows, and among the most beloved was “Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home” with the indomitable Madame Child. He created countless dishes in Julia’s iconic kitchen, whose delightfully anachronistic pegboards and beautiful copper pots are now on display at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

The duo’s nonstop light-hearted bantering became a storied part of their collaboration. Be it a debate about if the proper way to begin cooking a chicken dish—wash the bird or not. Or whether or not to squeeze water out of spinach. These small disagreements became their signature. (For the record, Julia firmly insisted that Jacques’ boil-and-squeeze spinach method resulted in a “slight bitterness.”)

“People always talked about the way Julia and I would argue on the show,” Pépin recalls. “She liked white pepper; I liked black pepper. I liked kosher salt, she didn’t. But really, you know, these were small differences, just for fun. We did agree on what’s important: the family sharing a recipe, the value of the best possible ingredients, the emphasis on taste more than presentation.”

Because of his long association with Julia, it is only fitting that Pépin is being honored with the first-ever Julia Child Award, to be presented to him at the American History Museum by world-renowned chef Daniel Boulud at a gala dinner on October 22.

Tanya Wenman Steel, director of the award, explains that once a short list of possible honorees was assembled, it quickly coalesced around him. “He exemplifies all the award’s criteria: educator, mentor, bridge-builder, tremendous integrity, great communicator. He has all of the wonderful qualities that Julia had.”

In Heart & Soul, likely the valedictory to his long career, the chef shows that he can go both ways: French and global, traditional and modern. The cookbook presents simple, easy-to-understand recipes for such classics as salmon rillettes, duck liver mousse, and cheese gougères, but these hallmarks of French cuisine mix it up with tostadas and tortillas lifted from the Mexican pantry and a chicken version of pho, the wonderfully aromatic soup from Vietnam.

And although Pépin may have strong feelings about which kind of pepper is best or the importance of choosing a good knife, make no mistake about it: He is no food snob. And what’s more, he is funny! In Heart & Soul, he writes of small fish such as sardines and anchovies, “Much is made of the omega-3 health benefits of eating oily fish. I’m a cook, not a doctor. I eat them because I like them, and if they happen to be good for me, all the better.”

Although he has now lived for so many years in the United States that he will tell you that he’s from Connecticut, not from France, he still retains the French reverence for certain culinary traditions, among them foraging. (Even today, every small-town French pharmacist will advise mushroom foragers about whether their specimens are poisonous or not.) Pépin used to run regularly in the woods near his home, and although he no longer does that quite as much, he still goes out in the fall and collects nature’s bounty–rosehips to make jelly, dandelion greens for salad.

“This year, I got 15 to 20 pounds of mushrooms. I use them for all kinds of things: stews, soups, sautéed with herbs. I put a whole bunch in the freezer. I clean them, put them in the oven then freeze them with their liquid.” Many of them go into the stuffing for his turkey at Thanksgiving, that most American of holidays.

Another French passion he has retained throughout his New World life is the love for organ meats. Young chefs in recent years have brought back a renaissance in so-called “nose-to-tail” eating, in which all parts of an animal grace the table, but Pépin never lost his enthusiasm for tripe, tongue and kidney. “Years ago, we made these things at home,” he says. “But we didn’t think they were for restaurants, at least not in America.” The new book includes not one but two tongue recipes—one for a cold beef tongue with ravigote sauce and the other for veal tongue.

But if nose-to-tail cuisine is not appealing, fear not—Pépin will never look down his nose at you. He has nothing but praise for real-life home cooks. “There is nothing more creative than feeding a family of six every night,” he maintains. “When you’re under a time constraint, to do it in an hour, that is really an achievement. And then to diversify the menu, to do it under a low budget—that is true creativity.”

Chef Daniel Boulud, who is creating a menu to honor Pépin at the award dinner, remembers that when he himself came to the U.S. in the early 1980s, Pépin was already here. “He was such a figure of French cuisine in this country,” Boulud says. “He was really the reference for French cuisine—for the American novice, even for professionals. He really wanted to make sure that people understood first and foremost.”

It was this ability to impart his knowledge that Pépin shared with Julia Child. “Jacques always enjoyed communication—teaching, doing TV shows, cooking, inspiring. And always in a very French way. Jacques is so French when you put him in the kitchen. Yet he is always interested in everything, from around the globe.”

Over the years, Pépin has added ingredients and recipes from around the world to his repertoire—hoisin sauce and the now-ubiquitous Asian sriracha sauce, sushi and Argentinian chimichurri sauce. He’s a fan of Wondra flour from the good old American supermarket and is not above picking up cooking tips from food TV star Rachael Ray (she didn’t peel the potatoes in a dish they were making together, and he decided to go with her method in future versions of the recipe).

But ask him about his last dinner in Julia’s kitchen and he seems to remember it as if it were yesterday.

A few weeks before the Smithsonian’s curators came to pack up the kitchen and its contents to be crated and sent to Washington, D.C., a fundraising dinner for 15 lucky souls was held at Julia’s house. Pépin, his old friend Jean-Claude Szurdak, along with ten students from the Boston University culinary program (where Pépin has taught for more than 30 years), created a menu to please Julia on the old Garland stove she loved.

“Believe it or not, after 45 years of friendship, that was the first time I ever ate in Julia’s dining room. Before that, it was always in the kitchen—her me, her husband my wife—but always in the kitchen,” Pepin remembers. “At the dinner, I kept moving from the dining room to the kitchen to cook with the students, from my friend Jean-Claude to Julia, constantly back and forth.”

The very French menu that night consisted of an oyster soup with fresh corn because Julia loved oysters, puffy cheese gougères, rillettes of rabbit, raie (the fish usually known as skate in the U.S.), a grapefruit granité (sorbet to the layperson), and much more, all accompanied by wines carefully selected by the team of Jacques and Julia.

Pépin has recently announced his donation of the menu from that long-ago meal, adorned with his colorful artwork, to the Smithsonian, so museumgoers will soon be able to stand, nose pressed against glass, and salivate over what Pépin fondly remembers as “an embarrassment of riches.”

Jacques Pépin Heart & Soul in the Kitchen

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Smiling-Anne.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Smiling-Anne.jpg)