Celebrating Master Chefs and Revolutionary Culinary Moments

Smithsonian’s Food History Weekend pays homage to José Andrés and other celebrity chefs; and places new artifacts on view

:focal(1271x485:1272x486)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/dc/d5dcd46f-6416-42a9-8846-b1bebd8baf52/cooking_up_history.jpg)

Out of the great American melting pot comes some pretty delicious food. At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, a newly re-opened exhibition, “Food: Transforming the American Table,” chronicles the development of cuisine in America over the past 70 years. This week, the museum kicks off its annual Smithsonian Food History Weekend with the Smithsonian Food History Gala. As it gears up to recognize José Andrés, famed chef and philanthropist at the helm of the disaster relief organization World Central Kitchen, the conversation is all about food and why it matters in the American story.

“How can you talk about food?” co-curator Steve Velasquez says. “What is that entry point? What is that intriguing object?” The answer lies in the modern look of the American plate—its new cultural influences, the advances of revolutionary food technology and the maintenance of tried-and-true cooking traditions.

The Museum’s “Food” exhibition first opened in 2012 as the popular home of Julia Child’s kitchen, which was transferred from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to the museum in 2001. Multitudes of visitors queue up at the exhibit’s windows and doors to peer into the world of America’s much-loved chef where her pots and pans hang on the pegboard walls just near her huge stove that she preferred to call “Big Garland.”

Food has since become a significant research focus for the museum’s curators and historians, who jumpstarted multiple collection projects on food, beverage and agriculture, and toured the country to collect stories and artifacts. “You can feel it when you meet someone who has a story they really want to tell—not just to you, but to a lot of people,” says the museum’s Paula Johnson, who directs the American Food and Wine History Project. “It’s about the food, but the cultural story is really front and center here.”

Display cases from the original exhibition outline technological advancements in the history of food production and processing, but now added to the mix are meal prep delivery boxes and “better for you” snacks, which have gained popularity since the show opened. Newer artifacts also showcase important countercultural food movements over the past several decades. Signposts from Alice Waters’ Berkeley, California restaurant Chez Panisse and artisanal goat cheese-making tools counterbalance the Krispy Kreme donut machine and Tyson TV dinner kits used to portray the industrialization of food production.

A host of stories detail the lives of chefs arriving as migrants from other countries and who helped shape American cuisine. Objects include the guestbook from “dine and learn” pioneer Paul Ma’s China Kitchen and a ceremonial Ethiopian coffee set from Sileshi Alifom’s D.C. restaurant, DAS.

Curator and food historian Ashley Rose Young says the museum team tried to offer stories that everyday Americans could relate to, as well as entirely new ones. The “Migrants’ Table” section celebrates the successes of certain immigrants’ journeys into the American food scene. The first frozen margarita machine and Goya microwavable tamale boxes represent the joint rise in food processing and packaging technology, and the introduction of more ethnic foods into the mainstream.

Mexican-American winemakers in California, men and women who came to the U.S. as the primary field laborers and in large part provided the backbone of the industry, are now revolutionizing winemaking as cutting edge vintners.

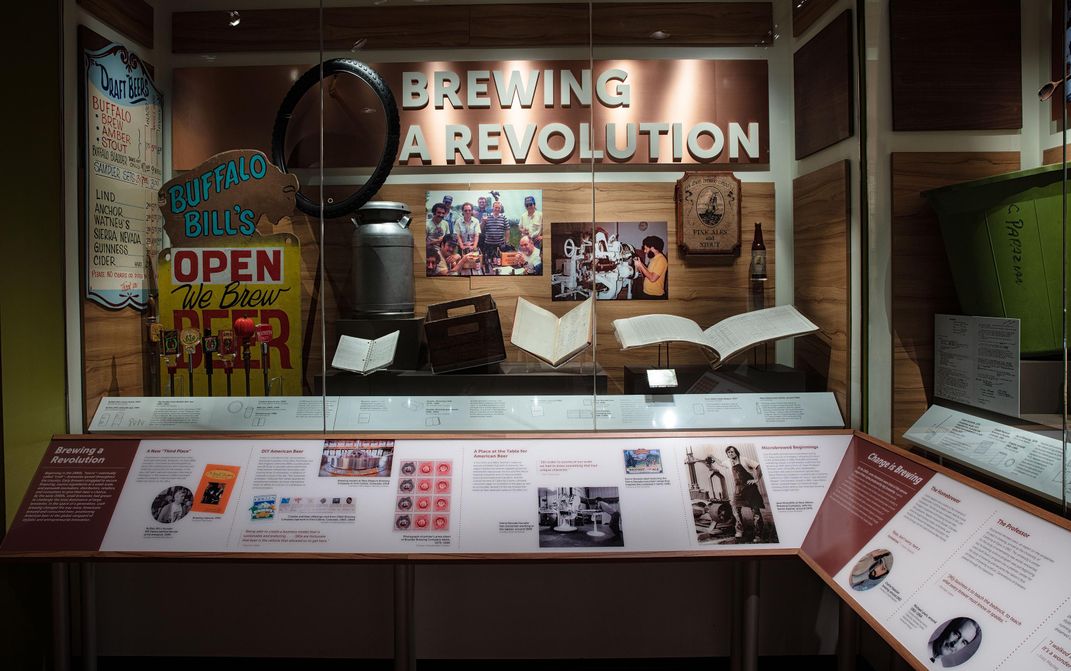

Similarly, the rise of craft brewing in the late 1970s re-shaped how beer was produced and enjoyed. A scratched milk can used in the early days at the New Belgium Brewing Company in Colorado and home-brewing pioneer Charlie Papazian’s beer-stained wooden spoon are unassuming, but they illustrate how pioneers in the industry worked before craft brewing entered the mainstream.

“These are prosaic, everyday items,” says Johnson, who adds that they resonate with meaning because of “how they were used, and the stories we collect that bring that into focus.”

At the monthly “Cooking Up History” at the museum’s demonstration kitchen, chefs create dishes like crêpes suzettes and Chinese congee, while Young, who hosts the events, engages them in conversations about the history and significance of the food and its traditions. Events planned for the weekend focus on the empowerment of migrant women chefs and restauranteurs. This includes demonstrations by Dora Escobar, Zohreh Mohagheghfar, Jacques Pépin and Genevieve Villamora of D.C.’s Bad Saint, and conversations about food activism and empowering refugee chefs.

Visitors won’t be able to eat the food prepared during the demonstrations. But as the stories and objects in this exhibit show, eating is only a fraction of understanding the story of food in the U.S.

“Food: Transforming the American Table” is on view on the first floor of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The museum’s fifth annual Food History Weekend takes place November 7 to 9, 2019. The Smithsonian Food History Gala and presentation of the Julia Child Award to José Andrés takes place Thursday, November 7.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)