There’s More to Classic Tiki Than Just Kitsch

Bartender Martin Cate reveals eight fun facts about the past, present and future of tiki culture

:focal(-312x-286:-311x-285)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/e9/c4e9a5fc-7001-45e7-ad7f-53b764ec809d/nmah-rws2012-05501.jpg)

Once associated with dopey midcentury kitsch, the elaborately decorated tiki bar is suddenly springing up everywhere, serving quaffable concoctions in pineapples and elaborately carved mugs.

In its heyday, the movement was even bigger. Its aesthetic spread beyond bars and restaurants to encompass otherwise distinct areas of American life: Car dealerships were built to resemble thatch-roofed huts and bowling alleys adopted imitation South Seas décor. That decades-long vogue eventually came to be known as Polynesian Pop.

On August 24, Martin and Rebecca Cate, of the acclaimed San Francisco bar Smuggler’s Cove, will speak at a Smithsonian Associates' event to discuss tiki’s legacy and share some of their own creations. In advance of that event, I spoke with Martin Cate about the rise, fall and resurgence of tiki. He led me through its historical underpinnings, explained what makes a good exotic cocktail, and speculated about why these fun (and sometimes flammable) drinks are popular again.

American tiki culture has origins dating back to the 19th century

The American fascination with what would come to be known as tiki culture begins more than 100 years ago. “Its origins go back to the 19th century, when Americans became quite interested in the South Pacific, tales of South Sea adventure, Robert Louis Stevenson and such,” Cate said. “Even into the early 20th century, we fell in love with Hawaiian music, creating this genre called haole music.”

Many other factors would continue to feed that interest over the years, including the Norweigan ethnographer Thor Heyerdahl’s harrowing 1947 journey from Peru to French Polynesia on a balsa wood raft that he had named the Kon-Tiki. To find the true starting point of tiki as we know it now, however, you have to go back 14 years earlier. In 1933, an itinerant and curious bootlegger named Ernest Raymond Beaumont Gantt opened a Hollywood restaurant that would come to be known as Don the Beachcomber.

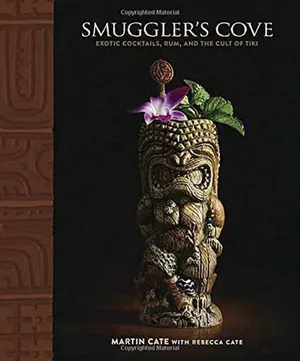

While Gantt decorated the space with relics from his nautical travels, it was the drinks—notably, complex multilayered rum concoctions—that really stood out. As Martin and Rebecca Cate write in Smuggler’s Cove, “Mixing and layering multiple spices and sweeteners provided a vast array of possibilities, and even small tweaks to a recipe could yield a much different result.” Thus, as the Cates write, was the exotic cocktail born.

Smuggler's Cove: Exotic Cocktails, Rum, and the Cult of Tiki

Winner: 2017 Spirited Awards (Tales of the Cocktail): Best New Cocktail and Bartending Book "Martin and Rebecca Cate are alchemists—Reyn Spooner–wearing, volcano-bowl-igniting, Polynesian-popping, double-straining, Aku-Aku swilling alchemists. Which is to say, they are the finest kind of alchemists known to walk the earth. Buy this book. It will bring you a little bit closer to paradise.”

Tiki bars arose during the Great Depression

While Don the Beachcomber was the first tiki bar, it obviously wasn’t the last. Imitators such as Trader Vic’s—the arguable origin point of the Mai Tai—soon began to spring up elsewhere in California and around the country. While the movement eventually assumed a life of its own, it might not have taken off if Don the Beachcomber’s island-themed aesthetic hadn’t been such a perfect fit for the economically troubled era.

“It created this escapist environment that fit perfectly with what people were looking for in Depression-era America,” Cate told me. “At a time before Internet and color TV and travel, it created an imaginary South Seas island getaway that was the perfect place to forget about your worries and troubles, and unwind with some soft music underneath a thatched roof.”

Tiki thrived during the post-World War II economic boom

If the Depression lit tiki’s fuse, it blew up during the post-World War II boom. One source of that growing enthusiasm, Cate suggests, may have been the huge number of G.I.s returning from overseas with fond memories of island downtime in the Pacific.

But, according to Cate, it was also important that theirs was a prosperous era.

“This was Eisenhower’s America. The Protestant work ethic. It’s nothing but work, work, work,” he said. “These tiki bars become the place where everything slows down. Where time stops. There’s no windows. It’s always twilight. You can loosen a tie and you can relax. They became these shelters that you could go to to decompress.”

Most classic exotic cocktails follow a strict formula

When Gantt—who would later rename himself Donn Beach, since everyone assumed that was his name—first began debuting exotic cocktails, he built them on the much older model of a drink called Planter’s Punch. Despite tiki culture’s Polynesian trappings, this seminal rum drink has Caribbean origins. “Remember, there’s no rum in the South Pacific, no tradition of cocktails,” Cate told me.

Traditionally, Planter’s Punch is built according to a simple rhyme that dictates its proportions:

1 of sour

2 of sweet

3 of strong

4 of weak

In the classic version, the sour is lime, the sweet is sugar, the strong is rum, and the weak is water. As Cate tells it, Donn Beach’s innovation was the realization that there was still room for experimentation within that formula.

“What Donn did, and this is what created these unique cocktails, which we call exotic cocktails, was to take these things and make them as baroque and complex as possible,” Cate said. “In so doing, he created yet another uniquely American form of cocktail, alongside these great historic things like the cobbler, the julep and the fizz.”

In an exotic cocktail, spice was more important than sweetness

While many treat tiki cocktails serve as a sugar delivery mechanism, Cate suggests that they’re missing the point. Donn Beach’s true innovation arguably derived from his willingness to raid the spice cabinet, introducing flavors such as pimento that Americans were only familiar with from their cooking.

“The essential parts are going to be a fresh citrus component and some kind of spice component,” Cate said. “The spice component can take the form of cinnamon syrup, it can take the form of a dash of angostura bitters. That was the secret weapon of Donn’s. That was what brought the layers in. Spices in tropical drinks.”

Though the tradition of using spice had deep roots in Caribbean cocktails, it lent an unexpected air of mystery in American bars. Bartenders continue to exploit this sense of surprise to this day, often embracing its potentially theatrical qualities. Some tiki bars, for example, will grate cinnamon over a flaming cocktail as it’s being delivered to the table, sending sparks into the air.

Exotic cocktails suffered a precipitous fall from grace

While Donn Beach and some of his immediate imitators made their complex drinks with, as Cate puts it, “precision and care,” tiki bartenders eventually grew careless. Part of the trouble was that many of the original recipes were closely guarded secrets (more on that in a moment).

“If you want to get into [exotic cocktails], it really does take a bit of effort,” Cate told me. “And it’s important, because this is where it all fell apart in the 1960s and, particularly, the 1970s. Bartenders had all these drinks written down as code. Getting recipes became a game of telephone.”

But Cate also attributes the decline to the mid-century vogue for cooking with powdered and canned foods designed to make the busy home chef’s life easier. Soon, bartenders were finding shortcuts such as substituting dry sour mix for fresh squeezed limes. Once subtle cocktails grew increasingly syrupy and indistinguishable, leaving us with the sickly sweet beverages that many associate with the movement today.

Recreating classic tiki recipes was hard work

As the art of exotic cocktails fell into disrepair, a few intrepid investigators attempted to pull it back from the edge of the abyss. Key among their number is likely cocktail historian Jeff Berry—author of books such as Potions of the Caribbean—who went to great lengths to recreate once secret recipes.

“It definitely took Jeff’s scholarship and his attempts to communicate with old bartenders who used to be in the trade to bring these things to light,” Cate said. “By doing that, he saved them virtually from extinction, but also put them on a platform where the craft cocktail bartender looked at them and said: 'I recognize a lot of what I do here. Housemade syrups, and great spirits and fresh juice.'”

The resurgence of tiki culture is partly a response to the craft cocktail movement

In the past 15-odd years, many bartenders once again began to think of their work as an extension of the culinary arts. Drawing on the lessons of farm-to-table cuisine, they started paying renewed attention to ingredients and technique. But that shift also brought an elevated level of self-seriousness to bars. As Cate puts it, “Everyone was in their sleeve guards with their waxed mustaches, telling their guest to hush. 'Don’t look at me, I’m trying to stir your cocktail. You’re going to bruise the ice by looking at it.'”

Though the new wave of tiki bartenders paid just as much attention to the details of mixology, Cate thinks that they also set out to deflate some of the pomposity. Serving their drinks in fanciful mugs with elaborate garnishes, they aimed to entertain.

“We can still adhere to the tenets established by Don the Beachcomber, and reestablished by the craft cocktail renaissance,” Cate told me. “Of course we’re going to use fresh made juice, we’re going to use quality rums, we’re going to use house-made ingredients, but what we’re going to do is bring our guests an experience that puts a smile on their face.”

"Tiki Time! Exotic Cocktails and the Cult of the Tiki Bar," is currently sold out, but names are being accepted for a wait list. The Smithsonian Associates program takes place Thursday, August 24 at 6:45 p.m.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.