Ajiaco, Cuba in a Cauldron

With origins in the island’s oldest culture, ajiaco is a stew that adapts to the times

:focal(714x1342:715x1343)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ad/94/ad9444f1-3a78-4d56-acec-e0f598358be8/sqj_1610_cuba_atlasofeating_02.jpg)

“Is there ajiaco today?” That was the first question my grandfather Julián would ask when he entered any of the Cuban restaurants spread across Miami. In quick succession he would ask it of the host who was seating us; he’d ask it of the busboy who was passing by; he’d ask it of the waitress before she distributed the menus.

If ajiaco was on the menu, usually as a rotating weekly special, he’d be rewarded with a bowl brimming with smoky cuts of pork, chicken, flank steak, and a dry cured beef called tasajo, along with rounds of starchy corn, golden sweet squash called calabaza, and plantains at every stage of ripeness. The broth could be light, or dense with the tropical root vegetables and tubers that had dissolved into it.

For my grandfather, it was everything he could want, flavors that evoked large family dinners and weekends spent on his ranch outside Havana where the guajiros (farmhands) would prepare large rustic stews. If more people turned up, a few more vegetables would be added so there would be enough for everyone. The next night it would be simmered down for a light soup. Then those leftovers would be milled together to make a smooth purée the following day.

I was never part of this life in Cuba. For me, ajiaco was an unfamiliar blend of rough brown vegetables and strange cuts of meat. My grandfather praised the tenderness of tasajo, but I saw little appeal in the dried beef covered in a thick layer of orange fat we’d find in the grocery store. It was a blind spot in my defiantly Cuban upbringing, like when a Spanish word eluded me but the English one was screaming in my ear. Though I can’t say that I appreciated ajiaco growing up, I did sense that it was fundamentally Cuban, something I should enjoy eating but didn’t. I never wanted to disappoint my grandfather by letting on that I didn’t like it. I hoped to spare him another reminder that we weren’t in Cuba after all.

Many years later, when I was writing a book of Cuban recipes, my research led me to the island, where I believed ajiaco could be the key to fully understanding Cuban cuisine. But what I found was that, like so many traditional dishes, it was more often talked about than tasted. Simpler versions could still be managed, especially in the countryside if there was immediate access to ingredients, but shortages persisted. Beef, in particular, was a rare commodity that was largely out of reach for most Cubans. Ajiaco had become a recipe of subtraction—but it didn’t start out that way.

According to food historian Maricel Presilla, when the Spanish came across the island’s indigenous Taíno population preparing the stew in clay pots over a wood fire, they would have recognized their own olla podrida, albeit with very different ingredients: Small game, like hutias (a local rodent), iguanas, or turtles; simmering with native vegetables like yuca, malanga, boniato, corn and squash; and seasoned with the burnt orange seeds of the achiote plant, which grows wild on the island. Its name came from the caustic peppers, or ajíes, the Taíno used for added heat. Although the elements of the concoction have changed since those times, its primacy as one of the few recipes with roots stretching back to pre-Columbian times is unquestioned.

In a recovered journal from the mid-1600s, maintained by a servant named Hernando de la Parra, early descriptions of ajiaco show a pronounced Spanish influence. Small game was replaced with the fresh meats and salt-cured beef from the livestock the Spanish introduced to the island, including cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, and chickens. But the indigenous roots and tubers, corn, and achiote were still present, as was casabe, a flatbread accompaniment made with shredded and dried yuca. Although de la Parra concedes the dish was largely consumed by the indigenous population, he notes that Europeans quickly became accustomed to this new way of eating, even to the point of forgetting their own traditions.

The push and pull between Old and New World ingredients would continue throughout the brutal years of colonization. Columbus’s second voyage in 1493 brought the sour oranges and limes that would become the basis of creole marinades. Onion and garlic were combined with indigenous peppers to form the trinity at the heart of traditional Cuban cooking. Plantains and yams called ñames arrived from West Africa soon after and were closely associated with the large African population brought to the island as slaves to toil in mining and agriculture, and to supplement a Taíno labor force decimated by famine and disease. Though it’s unclear exactly when these foods were added to the stew, all these ingredients were listed when ajiaco recipes were finally recorded in 19th-century cooking manuals.

Despite the intense social stratification that existed, ajiaco was one of the few dishes that seemed to cross all barriers—a peasant meal ennobled by its origin story. In Viaje a La Habana, a memoir published in 1844, the Condesa Merlin Mercedes Santa Cruz y Montalvo chronicled her return to Cuba after several years in Europe.

Noting the dichotomy that existed among elite, native-born Creoles, she describes the show they made of serving hyper-refined European delicacies to guests, while taking comfort in familiar, tropical foods in private. She rejects an aunt’s efforts to present her with an elaborately prepared French recipe, choosing a simple ajiaco instead, asserting, “I have only come to eat creole dishes.”

For the emerging Cuban-born aristocracy, flush with capital but facing volatility both in sugar markets and politics (the revolution in Haiti at the turn of the 18th century sent shock waves), the European style of cooking projected wealth, stability, and cosmopolitan sophistication. There are 19th-century descriptions of parties where ajiaco was served, but only if no foreign guests were present. Tropical ingredients and ajiaco in particular became synonymous with Cuba’s roots and a growing drive to embrace them.

As Cuba moved toward independence from Spain in 1898, the shaping of a national character grew in importance. In the decades that followed, poets, writers, and academics looked to better define the country’s identity. Ajiaco, with its blended, or mestizo, culinary heritage, became a favorite metaphor in the criollista movement, which embraced Cuba’s Indian and black heritage.

Most famously, the preeminent anthropologist Fernando Ortiz compared all of Cuba to an ajiaco: “This is Cuba, the island, the pot placed in the fire of the tropics…. An unusual pot, this land of ours, just like the pot of our ajiaco, which must be made of clay and quite open,” wrote Ortiz in a lecture delivered at the University of Havana in 1939 and published in 1940. “And therein go substances of the most diverse types and origins…along with the flush of the tropics to heat it, the water of its skies to compose its broth, and the water of its seas for the sprinklings of the salt shaker. Out of all this our national ajiaco has been made.”

Not only did he celebrate the confluence of Taíno, Spanish, and African cultures in the making of ajiaco, he also cited other surprising influences, including Eastern spices introduced by Chinese laborers and mild peppers brought by immigrants fleeing revolutionary Haiti. He even pointed to Anglo-American ingenuity, although with ambivalence, for simplifying domestic life and producing the metal cookware that replaced traditional clay pots used for making the stew.

It wasn’t the final savory result that made Ortiz see Cuba in the cauldron but the process of cooking—varied cuts of meat disintegrating after a long simmer, and vegetables and fruits added at certain intervals to create new textures—a “constant cooking” that was always evolving, creating something new.

It’s harder to know what Ortiz would have thought of this quintessentially Cuban dish establishing itself on the other side of the Florida Straits. But for many Cubans in the diaspora, the longing to connect to their country is fulfilled at the stove. The ritual of finding the right ingredients—the roots that are at the base of the stew, the special cuts of beef or pork, the plantains in various stages of ripening—are ways to experience the island from afar.

Ajiaco has a place in my life, too. My grandfather’s yearning for the dish awakened my curiosity. I now take comfort in the flavors, learning something new with each attempt at the recipe, and never taking a single spoonful for granted.

Recipe: Ajiaco Criollo

This version of ajiaco comes from Miguel Massens, a young Cuban-American chef.

FOR THE MEATS

½ pound tasajo de res (smoked, dried beef)

2 pounds bone-in, skinless chicken thighs and drumsticks

½ pound flank steak or brisket, cut into 1-inch cubes

½ pound bone-in aguja de cerdo (pork collar bones), pork ribs, or ham hock

¼ pound boneless pork loin, trimmed of any excess fat and cut into 1-inch cubes

FOR THE VEGETABLES

1 pound boniato, peeled and cut into 1-inch rounds

1 pound malanga, peeled and cut into 1-inch rounds

1 pound yuca, peeled, cored, and cut into 1-inch rounds

½ pound ñame (or white yam), peeled and quartered

2 ears corn, shucked and cut into 2-inch rounds

2 large green plantains, peeled and cut into 1-inch rounds

2 large yellow plantains, peeled and cut into 1-inch rounds

1 pound calabaza (sold as West Indian pumpkin), peeled, seeded, and cut into 1-inch cubes

1 chayote, peeled and cut into 1-inch cubes

FOR THE SOFRITO

5 large garlic cloves, peeled

1 tablespoon kosher salt

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1 teaspoon ground cumin

½ cup freshly squeezed sour orange juice or lime juice

¼ cup loosely packed fresh culantro (found in Latin markets), finely chopped

¼ cup achiote oil

1 medium yellow onion, minced

5 cachucha peppers (also known as ajies dulces), stemmed, seeded, and diced

1 large cubanelle pepper (also known as Italian frying pepper), stemmed, seeded, and diced

1 small fresh hot pepper (habanero, Scotch bonnet, or tabasco), stemmed, seeded, and minced (optional)

Lime juice to taste

Soak the tasajo to remove some of the salt, changing the water twice, at least eight hours at room temperature or overnight. The next day, drain the tasajo and rinse well under cold water.

Add the chicken, flank steak, pork collar bones, and pork loin to a heavy eight-quart stockpot with five quarts of water and simmer until tender, skimming off any impurities that rise to the top, about one additional hour.

Add the boniato, malanga, yuca, ñame, and corn to the pot and continue to cook covered until the root vegetables are just tender, about 20 minutes. Add the plantains, calabaza, and chayote and continue to simmer until tender, an additional 10 to 15 minutes. Replenish the water if needed. Allow the stew to cook at the stove’s lowest setting until the meat falls from the bone and shreds easily, 30 to 45 minutes.

In the meantime, prepare the sofrito. Using a mortar and pestle, mash the garlic, salt, black pepper, and cumin to form a smooth paste. Stir in the sour orange juice and culantro and set aside.

Heat the achiote oil in a 10-inch skillet over medium heat. Add the onion and cachucha peppers and sauté until the onion is translucent, six to eight minutes. Add the garlic mixture and combine with one cup of broth and one cup of root vegetables taken from the stew. Mash the vegetables into the sofrito and simmer until well blended, about five minutes. If using, add the minced hot pepper to taste. Add the entire sofrito to the stew and simmer an additional 10 to 15 minutes.

Adjust the seasonings to taste. Remove the chicken bones and pork bones from the stew. Ladle the stew into individual bowls and sprinkle with lime juice. Serve with warmed casabe (yuca flatbread) and fresh lime wedges.

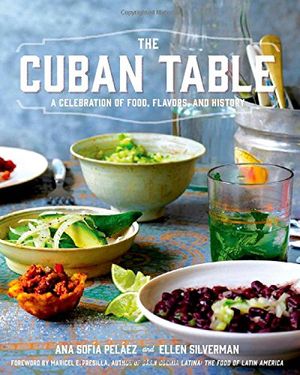

From The Cuban Table, by Ana Sofía Peláez and Ellen Silverman. Copyright © 2014 by the authors and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

Read more from the Smithsonian Journeys Travel Quarterly Cuba Issue

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.