Cappadocia’s Fairy Chimneys and Cave Dwellings

Doorways still lead into cool, cozy chambers where people grilled kebabs, served tea and worshiped until 1952

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111018095012cappadoccia-turkey-alastair-bland.jpg)

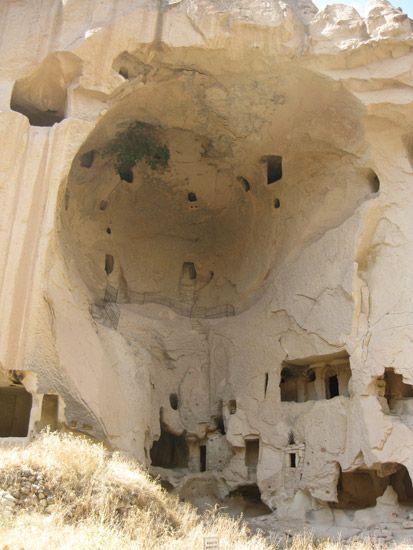

This country is plain weirdness, and the history of the cave-dwelling communities of Cappadocia is as peculiar as the landscape itself. The place bears a resemblance to the Badlands or parts of Utah; so-called “fairy chimneys” spill out of canyons and off mountains, created when erosion sheared away the top layers of soil and left these unearthly spires. The element of ancient human culture adds a mystical quality to the geologic beauty; old doorways and windows from defunct societies remain in the rock like the eye sockets of unearthed skeletons. Who, they beckon us to wonder, once peered from them? When? And, with all the real estate available elsewhere, why?

Fresh off the bike after the long haul from Ankara, at sunset I take in Cappadocia from a distance on the rooftop terrace of the Bir Kedi bed and breakfast, on which I’ve splurged for a night. The owner, an Italian named Alberto, lives here from April to October. The winters in Cappadocia are continental—frigid with several feet of snow—and this has two significant consequences: There are no figs, and, in the winter, year-round residents burn coal to keep warm.

“When the wind blows north from town, man, you can’t breathe here,” Alberto says, and though many people hack out their lungs all winter, Alberto goes back to Italy when the tourists thin out and the black smoke begins to billow.

After a comfortable night spent sending emails and writing in bed, I eat breakfast with the other guests, two of whom are young French backpackers hitchhiking to Thailand. Then I set out southward into the weirdo world of Cappadocia. Hot air balloons float overhead. At Zelve, a cave town carved centuries ago into the stone walls of a deep canyon, I pay the 8-lira entrance fee and walk into the village. Doorways still lead into the rock, into cool, cozy chambers that cave-dwellers once called home. They had guests for dinner, grilled up kebabs, served tea, chewed sunflower seeds on the stoop, read books by the coal fire, called out “Çay!” if a cyclist appeared—and they did so all the way up until 1952, when they left the crumbling settlement en masse. Today, visitors will even find in Zelve a church, a mosque and a monastery, each hollowed out of the soft stone.

In Göreme, a hive of tourist activity and shops selling cave-dweller paraphernalia, rugs, other assorted souvenirs and a million postcards, I can’t find a thing to eat.

“How can a whole town not have a melon vendor?” I wonder. I haven’t eaten since morning. Then, outside the Nature Park Cave Hotel, I find two huge, gnarly-trunked mulberry trees. The trees are loaded with plump black berries within easy reach. Thirty minutes after diving in, I emerge from the foliage draped with cobwebs and sticky with crimson juice. Two pretty British women walk past. Oops. time to get clean, I think, and I roll to the mosque for a wash-down. As I sit and scrub at the mosque-yard fountains, the afternoon prayer call begins, drawing men who wash their feet at the spigots before entering the mosque to pray. I feel like an infidel—unshaven, quite dirty (forgot to shower at the guesthouse) and my main concern of the moment being what wine I’ll drink tonight.

I find a fruit market, buy my dinner and a Turkish Chardonnay and pedal into the scrub country. I camp on a plateau and watch the sun set as Cappadocia ends another day of history in shades of orange and blue. The wine tastes like paint thinner, and I notice then the vintage: 1998. I think back. I was fresh out of high school. France was still on the franc. Wolves were re-colonizing Montana. The George W. Bush era was yet to begin—and sometime during his second term, I reckon, this wine went south.

In the morning, I meet a German cyclist named Ingolf in Göreme. I tell him I feel obliged to stay here longer, to see, for one thing, Cappadocia’s old underground cities.

“We’re tourists, and it’s our job to do these things,” I say, only half joking.

Ingolf puts my head back on straight. He says we aren’t tourists but bike tourists and that the greatest places are those uncharted, unpaved and unnamed—and to which we have access. He has just come from the Toros Mountains in the south, and he’s ready to return to the high country. One night here, he says, is plenty, and he adds brazenly: “If you’ve seen one cave in the rock, you’ve seen them all.” The words come off like blasphemy, yet it’s the most refreshing thing I’ve heard since the hiss of an espresso machine in Bulgaria.

Alberto at Bir Kedi had tried to convince me that one must spend a week sightseeing to truly know Cappadocia. (More realistically, one must probably spend a lifetime.) But I’m experiencing Turkey through the eyes of a traveler. That’s the whole point: I come, I glance, I go—and so I go. I take a bus 200 miles across the flats of the great Turkish inland sea, Lake Tuz, and by nightfall I’m camped in the cool mountains east of Konya. If I develop a sudden craving for a postcard or a cheap bracelet, I’ll be out of luck—but I’m sated on silence and the sunset.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)