Eat Like a Parisian in a Parisian Apartment

An Internet-based service allows visitors an authentic taste of food, friendship and culture

For many years when going to faraway places, I would eat in private homes. I was a foreign correspondent, and many kind and curious locals would invite me to share a meal. Whether sampling a dollop of walnut sauce or savoring a sliver of poppy cake, I would learn about a family and, by extension, a culture, through food. When I returned to the United States and started traveling as a regular tourist, I missed the warmth and intimacy of eating in people’s homes.

That’s why, when planning a trip to Paris recently, I jumped at the opportunity to try Eatwith.com. The Internet-based service offers home-cooked dinners prepared by one of the “hosts” in his or her home. The system is straightforward: Eatwith’s hosts post their menus, list the languages they speak, and say a few things about their personal interests. The guest pays upfront online at a fixed price; the evening itself is free of transactions.

To my surprise, there were only ten hosts for all of Paris, some of whom catered to travelers looking for vegan or ayurvedic (an ancient Indian approach to balanced eating) cooking. Other more established Eatwith cities, like Tel Aviv and Barcelona, have larger rosters. But several choices matched my preference for classic French cooking, including Claudine (A Parisian Dinner in Montmartre, $50) and Alexis (Un Hiver Bistronomique, $59). They emphasized the care with which they shopped for seasonal produce and high-quality ingredients. I booked them both, deciding to participate as a guest, not a journalist. (Later once I decided to write about the experience, I recontacted them.)

Small lanterns cast a soft glow through the large living room. A gilded rococo mirror sparkles. The ceilings are high, and the walls are covered with paintings and folk souvenirs, many from Indonesia. My husband, Joel Brenner, and two Parisian friends, Katherine Kay-Mouat and her 15-year-old-son, Maximilien Bouchard, have settled into comfortable chairs around an enormous rattan coffee table at Alexis’s 8th arrondissement apartment, right around the corner from the celebrated music hall Folies Bergère.

I bite into a crispy homemade chip that Alexis is serving. “Do you know what they are made of?” he asks. I venture a guess: Taro root? I’m wrong; it’s another nubby vegetable: Jerusalem artichoke. The conversation stays on a culinary course. “How do you make them so thin?” Katherine asks. “Easy,” says Alexis. “You just use a mandoline slicer.” Not easy, I think, knowing from experience the skill needed to manage the mandoline’s sharp blades. Alexis offers a toast to the evening ahead, and we all clink glasses filled with sparkling Vouvray. Katherine asks another question, and Alexis gives a sly smile. It’s one he gets all the time: How did you get interested in making meals at your home, in joining Eatwith?

Alexis, who is 28, explains how he decided to abandon the field he had trained in (business) and switch to a culinary career. He’d heard about Eatwith from a friend and realized he had the requisites in place: A passion for cooking, fluent English, and the run of his parents’ gracious apartment.

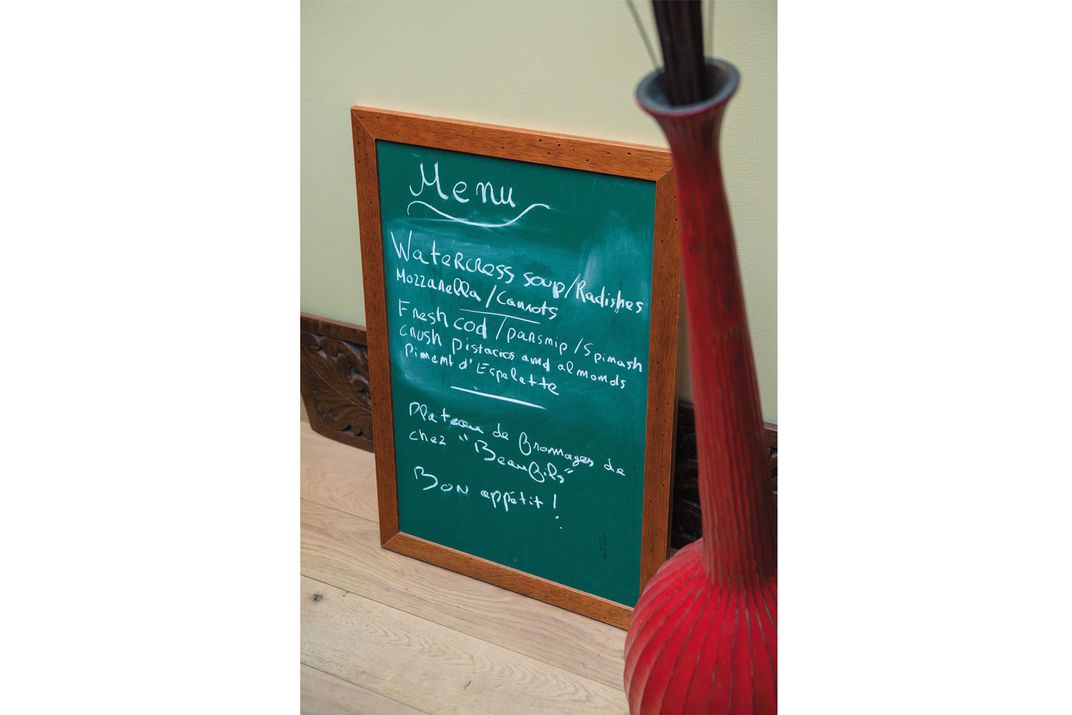

This evening he serves watercress soup with shredded buffalo mozzarella, poached cod on a bed of mashed parsnips and potatoes, a plate of French cheeses, and homemade chocolate truffles. Alexis’s life revolves around food—fresh, organic, and lesser known ingredients. His voice chokes with indignation when he tells me during an interview that France is second only to the United States in the number of McDonald’s hamburgers it consumes.

At Claudine Ouhioun’s apartment, a fire is burning in a small marble fireplace when Joel and I arrive at the apartment. The light is low, candles are lit, and the table is set with glistening crystal wine glasses. I ease into a gloriously French armchair—a bergère upholstered in Pierre Frey linen with a design in the shape of ferns. Nearby is a chest of drawers in the Louis XV style that has been in her family for at least a hundred years.

Claudine, 65, a recently retired English teacher at a local lycée, introduces the guests: Arial Harrington, who lives in Brooklyn, is launching her own clothing line. Her friend Matthew Fox, 27, works for an event planning company in Washington, D.C. Arial, 29, tells me that she sought out the Eatwith experience because as an aspiring cook, she is considering becoming a host herself. When she rises spontaneously to tend the fire, poking the embers and adding a log, much as a close friend or family member would do, I reflect on how the shared economy has equalized the relationship between consumer and service giver. Claudine is pleased by the casual friendliness of the gesture. She tells me later that the exchange of emails that’s customary before each meal makes her feel she is hosting friends, not guests. This, too, seems a sea change. When I lived in Paris in the 1970s as a student, my landlady pointedly told me not to expect the French to want to be friends. A fellow café habitué admitted he made his friends in Boy Scouts and had little desire to widen the circle.

Claudine slips into a galley kitchen to assemble the verrine, a starter made of chopped cooked beets with a layer of Greek taramosalata on top—an inspired combination. Parisians love taramosalata,” she tells us. “It’s not true what they say about the French only wanting to eat French food.” But Americans visiting in Paris do often want classic French food, and everyone is happy to dig into Claudine’s pot-au-feu. She has tweaked the boiled meat/root vegetable recipe by using warm spices—allspice, or maybe cloves—to add a hint of North Africa in the flavor.

It’s cozy and relaxed. As I eat and sip wine, I think of the pluses and minuses of dining this way: The food may not reach the heights of a fine Parisian restaurant, but the advantages of heartfelt hospitality (versus the potentially grumpy or haughty waiter) and conversation with people you might not normally meet more than compensate. Eating with Alexis and Claudine reminds me of the pleasure I felt corresponding with pen pals as a schoolkid. I get to bombard them with every manner of question without feeling the least bit impertinent.

Pen pals are out of fashion. Facebook friends are not. Both Alexis and Claudine stay in touch by social media and email with former guests, mostly foreigners, some of whom call when they are back in Paris and invite them for an evening out. Or, as in the case of Raymond Mendoza, a Francophile from Pomona, California, return with a gift. When Raymond came to Paris on his annual visit recently, he stowed a half dozen homemade cheesecakes in the overhead compartment. He had boasted to Alexis and other French friends about his sophisticated redo of the classic dessert, made with a macadamia nut crust and a pear custard-cream cheese filling. When Alexis pronounced it délicieux, Raymond was over the moon. Laid off from a job in banking, the Californian is contemplating what to do next. He too will soon try his hand at being an Eatwith host.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.