During those first few weeks of the Covid-19 outbreak, the Rome newspaper Il Foglio ran a panicky headline that proclaimed “La morte del bacio” (The Death of Kissing). In the age of social distancing, Italians wondered if smooching would soon go the way of the Roman Empire. One hundred and forty miles down the coast, in Naples, where restaurants were twice shut down in lengthy lockdowns, natives mulled a more existential threat: La morte della pizza. Would the virus be the Neapolitan pie’s kiss of death?

Faced with a financial meltdown of Pompeiian proportion, the pizzerias of Naples tweaked their centuries-old business models to fit the moment, ushering in such previously blasphemous practices as home delivery and—heaven forfend!—pizza kits. “Eating pizza is not a Naples norm that will be upended by the pandemic,” maintains Luca Del Fra, an official with Italy’s cultural ministry. “Pizza is economical, it’s fast, it’s Naples. So I doubt the public will forget.”

Naples is the birthplace—and, as any Neapolitan will tell you, the spiritual homeland—of pizza. In this southern Italian city of 963,000 people and 8,200 pizzerias, it’s said that fathers want their sons to be one of two things: soccer players for SSC Napoli or pizza chefs, called pizzaioli, or in the local dialect, pizzaiuoli.

There are 15,000 pizzaioli in Naples, and the virtuosos are like pop stars, admired, even revered, with fervent followers who seldom stop arguing about their favorite’s place in the pizzaioli pantheon. “All Neapolitan pizzamakers think they are the best in the city, even if all their relatives are Neapolitan pizzamakers,” says Francesco Salvo, whose grandfather, father and two brothers are pizza chefs, too. “The essence of Neapolitan pizza is family sharing its passion. Your execution must be meticulous, because if you let quality slip, you are cheating on your family tradition, which is like cheating on your wife.” The exacting standards of these pizzaioli are responsible for changing the perception of the fare from a humble pie into a deeply respected cuisine.

The classic Neapolitan pizza is as soft and floppy as a basset hound’s ears. It’s chewy rather than crunchy, with a moist if not soupy top, abundant scorch marks (“leoparding”) and an airy cornicione, the pillowy ledge that frames the crust. The steamy crust is blast-cooked to perfection in 90 seconds or less at about 900 degrees—almost double the temperature of most American pizza ovens—and is thinner than the plate it’s served on.

“What most distinguishes Neapolitan pizza is the ferocious heat in which it’s cooked and the soft, supple pliability of the dough,” says Zach Pollack, chef and owner of Cosa Buona, a Naples-inspired pizzeria in Los Angeles. “Everything is about the dough. When a pie is so dough-centric, you get a totally different outcome than if the toppings are the focus of the event.”

Consisting of only water, salt, yeast and highly refined wheat flour, Neapolitan dough is the most elemental of all formulas, but the apparent simplicity hides a great complexity. The maestros allow their dough to ferment anywhere from 12 hours to several days. The only thing that keeps it from levitating above their heads are gently oozing splodges of buffalo mozzarella from the marshlands of the southern Apennines and blobs of pulpy plum tomatoes, grown in the volcanic soil of Mount Vesuvius. This combination of bright acidity and sweet, cheesy smoothness inhabits that taste space the Japanese call umami, or pleasant savory flavor. A Neapolitan pie is designed to be consumed fresh and hot, as close as possible to the igloo-shaped oven in which it was cooked.

Perhaps the pie’s most important virtue is digeribilità (digestibility), a charming term for pizzas that are easy to eat, and that your body welcomes with seeming effortlessness. Though some American pizzerias reach those lofty heights, most Americans buy their pizzas frozen or eat them at churn-and-burn pie chains. The dough has been turbo-boosted with sugar to rise quickly, and an unctuous sea of cheese and meat has been piled atop rubbery underdone or brittle overdone crusts, sometimes occurring in the same pizza. (The quality of the tomato sauce? Not a consideration.) “Frankly, what passes for pizza abroad is all too often a travesty,” Neapolitan pizzaiolo Ciro Moffa has lamented. “Enough is enough!”

Neapolitan pizza is not just a source of epicurean pleasure and civic pride; its preparation is considered an art form, one that four years ago Unesco, the United Nation’s cultural arm, elevated to “intangible cultural heritage” status alongside such practices as Indian yoga, South Korean tightrope-walking and Burundi’s ritual dance of the royal drum. Ironically, Naples’ treasured “intangibles” are made tangible every day in pretty much every major city on earth. But despite dozens of regional adjustments (think the tomato pies of New Jersey, the “apizza” of New Haven, the Provel cheese and crackers of St. Louis), no variation, no matter how delicious, is as central to the local culture as pizza surely is to Naples.

“Pizza here is thoroughly rooted in the community life,” says Gino Sorbillo, whose eponymous Naples pizza palace has offshoots in Milan, New York, Rome, Tokyo, Miami, Genoa and, soon, Abu Dhabi. “It’s the soft warmth of the Mediterranean sun. It’s the violence of Vesuvius. It’s the great moments of humanity the city offers at every street corner. In Naples, pizza is more than just food: It’s the identity of the people.”

Four hundred years ago, Caravaggio revolutionized painting with a chiaroscuro style reflecting the splendor and squalor of Naples—brightness and light contrasted with the blackness of deep, menacing shadow. “It’s a dark, enchanted city,” the American actor and director John Turturro told me. His 2010 documentary Passione is a rapturous celebration of Neapolitan music. “When Odysseus’ ship stopped nearby on the way back from the Trojan War, the sorceress Circe mixed a magic potion that turned most of his crew into swine. Today, the natives call their hometown La Strega—The Witch—and say, ‘Come to Naples, lose your mind and then die.’ They’re fatalistic, and yet the coffee and the pizza have to be perfect.”

* * *

Sprawling and endlessly vibrant, Naples marries joyous confusion with a sense of mild danger. The city’s insalubrious reputation derives from its recent history of mounting garbage, ceaseless traffic and the depredations of one of Italy’s oldest organized-crime syndicates, the Camorra, whose moped-straddling banditos zoom the wrong way down the medieval warren of one-way streets. Along those narrow alleys, wrought-iron balconies drip with buntings of faded laundry, and walls are buried beneath layers of posters, graffiti and grime.

In the belly of Old Naples squats Antica Pizzeria Port’Alba, the world’s oldest pizza parlor. Port’Alba was established in 1738 as an open-air stand for peddlers who got their pies from the city’s bakeries and kept them warm in small, tinned copper stoves balanced on their heads. The stand expanded to a restaurant with chairs and tables in 1830, replacing many of the street vendors. Twelve years later, Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies, otherwise known as King Nasone (big nose), came incognito to the pizzeria to survey the mood of his people. “The king probably ordered aal’olio e pomodoro,” says Gennaro Luciano, the current proprietor. That’s the pizza topped with tomato sauce, oil, oregano and garlic that’s commonly called marinara, derived from la marinara, the fisherman’s wife, who typically prepared the dish for her husband when he returned from trawling in the Bay of Naples.

Luciano is a sixth-generation pizzaiolo with shambling charm and a studiously unkempt style. “Neapolitan pizza-making is not acrobatic,” he says flatly. “No flipping, no juggling, no DJing, just the art of lavorazione, the way the dough is worked.” That art informs every aspect of Luciano’s technique, from kneading and flattening (he says the dough has been ammaccata, “crushed”) to the blister and puff of a pie’s cornicione.

He’s explaining this between bites of pizza a portafoglio, literally a “wallet pizza” that has been folded in half and then quarters. Since the tomato sauce has been gathered and protected in the folds, Luciano recommends holding the pie out away from your shirtfront. Port’Alba claims to have invented this portable street food, and for nearly three centuries has stocked the eight-inch mini-pies in a display case by the entrance. “Without the glass case, Pizzeria Port’Alba would no longer be the Pizzeria Port’Alba,” says Luciano. “Customers stopped in to buy portafoglio when they were students; now they return with their grandchildren.”

Luciano is 59 and has been making pizzas for the last 46 of those years. He’s packed with an endless supply of pizza lore, which he retails more or less nonstop for hours, pausing only to stoke the fire in the back of Port’Alba’s lava-lined oven with kindling and small chunks of oak. He says that not far from his pizzeria, in the Greco-Roman ruins beneath the 18th-century cloister at San Lorenzo Maggiore, are the remains of a first-century A.D. Roman market, a shopping arcade and a proto-Neapolitan pizza oven. Similar baking chambers, with hollow spaces to insulate hot air, drafts for smoke and terra-cotta tile floors, were found during excavations at nearby Pompeii and Herculaneum. Inside some were loaves of bread, preserved in charcoal, covered in ash and stamped to identify the baker. One 2,000-year-old loaf was divided into eight wedges and inscribed: Celer, slave of Quintus Granius Verus.

The story of pizza, says Luciano, dates to Neolithic times, when tribes baked a crude batter on the stones of their campfires. The Neapolitan variant was the product of two cultures, Greek and Etruscan. The Greek city-states feasted on plakous, a flat and round cheese pie with a rim of crust that served as a kind of handle. From the eighth century to the fifth century B.C., the Greeks colonized the coastal areas of southern Italy that made up Magna Graecia, bringing their “edible plates” along. It has been speculated that pita, the English word for a flat hollow unleavened bread, had etymological roots in pikte, the ancient Greek term for “fermented pastry,” which in turn passed to Latin as picta, hence pizza.

At about the same time, says Luciano, the Etruscans left Asia Minor and settled in the northern and central parts of Italy. Their pizza dough precursor was a sort of grain mush baked in the stones beneath cooking ashes and topped with herbs and seasoned oils. After swallowing Etruscan folkways whole, the Romans renamed the ashcakes panis focacius (fireplace flour bread), which evolved into focaccia.

Luciano grabs a tomato from a ceramic bowl, holds it aloft and sinks his teeth into the fleshy pulp. “This changed the face of flatbread,” he says. “The tomato gave Neapolitans the right to claim pizza as our own.”

In the early 16th century, Spanish conquistadors returned from the New World with an exotic, yellow, cherry-size fruit that the Aztecs called the tomatl. Fear and loathing were quick to follow. In 1544, the Italian botanist and physician Pietro Mattioli was the first to formally classify the plant, likening it to a cross between mandrake and deadly nightshade—both poisonous. Soon the tomato was tarred with the Latin name lycopersicum, literally “wolf peach.” Wolf because of its alleged toxicity; peach due to its shape and texture. Word spread that wealthy people got sick and died after consuming tomatoes, and for some 200 years, most Europeans avoided them like the plague, which, incidentally, nearly eradicated the population of Naples during the mid-1600s.

As it turns out, says Luciano, it was all a big misunderstanding. The wealthy ate their food off pewter, an alloy with a high lead content. Combined with the tomatoes’ acidity, the flatware would leach lead, sometimes resulting in the diner’s death. The poor, on the other hand, used plates made of wood. “They could eat tomatoes and not get sick,” he says. It wasn’t until the invention of pizza, somewhere in the early 1700s, that tomatoes began to gain wider acceptance.

Pizza took a little longer. Though it nourished the poor of Naples, who substituted tomato sauce for meat, the piquant dish wasn’t to everyone’s liking. Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph, described pizza, which he sampled on a visit in 1831, as “a species of most nauseating cake” not unlike a piece of bread “that had been taken reeking out of the sewer.”

The 19th-century slight elicits a laugh from Luciano. Oven logs crackle continuously in a low, ominous mutter as he pads through the age-softened galley, occasionally lifting up the crusts of pies to check that they are properly cooked—elastic, but not limp and not burned like toast. “The magical breakthrough of pizza came in 1889,” he says. “That was when Queen Margherita of Savoy, consort of King Umberto I, observed peasants in Naples enjoying the people’s food.”

Supposedly, the queen summoned the city’s most famous pizzaiolo, Raffaele Esposito, to the royal residence on Capodimonte Hill and had him prepare three pizzas for her. This was 28 years after the unification of Italy, and the pie she liked best bore the colors of the new national flag: tomato red, mozzarella white and basil green. So pleased was Her Highness that she sent Esposito a letter of thanks. So flattered was Esposito that he named this tricolor sensation the margherita.

“At that moment pizza conquered the world,” Luciano says.

* * *

The patron saint of Neapolitan pies is Sophia Loren, who grew up just outside the city. Her canonization was propelled by the 1954 movie L’Oro di Napoli (The Gold of Naples), in which she played a seller of pizza fritta, deep-fried half-moon pockets stuffed with ricotta and crispy bits of fatty pork. Though Neapolitan pizza-making is dominated by men, the wives of pizzaioli played a key role after World War II, hawking fried pizza—the original pie, born before the oven-baked variety—to the poor. “Standing before an oven was an arduous task, so making traditional pies was a man’s job,” explains Isabella De Cham, Naples’ most renowned female pizzaiolo. “Instead of costly mozzarella, fried pizza used common ingredients and was smaller in size, which made it easier for feminine hands to fold.”

* * *

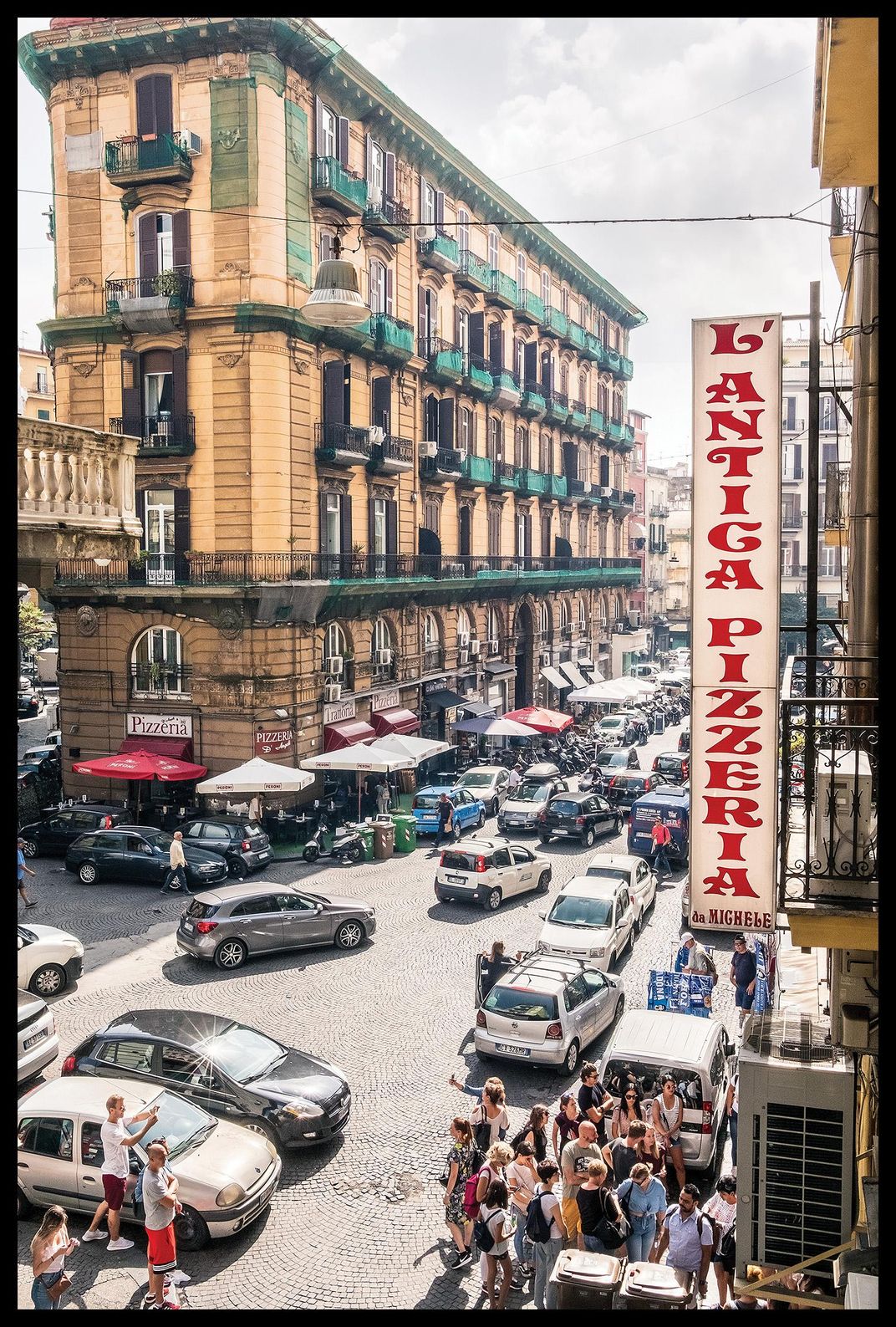

L’Antica Pizzeria Da Michele, a storefront operation, is tucked behind the 14th-century Duomo in the working-class Forcella neighborhood. The peppery scent of basil and the aroma of warm dough precede the place, a pair of dining rooms watched over by a statue of St. Antonio Abate, the patron saint of bakers, enshrined in a neon-lit glass cabinet.

Da Michele is the most determinedly traditional of all the Naples pizzerias. Paterfamilias Salvatore Condurro got his license to make pizza in 1870. He prepared and sold fried pizza on the street outside his home. Since 1930, when his son Michele opened the family’s first pizza emporium, the Condurros have been turning out marinaras and margheritas and...nothing else. The waiters, whose white polo shirts bear the phrase “Il tempio della pizza” (the temple of pizza), dismiss all other forms as papocchie—Neapolitan slang for phony tricks.

Thirty-six years ago the Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (AVPN), established by the city’s 17 most prominent pizza-making families, set up a protocol to promote and protect the reputation of “true Neapolitan pizza.” Accordingly, any pizzeria that wants to display the association’s logo—and in Naples only 125 (less than 2 percent) have made the grade—must make its marinaras and margheritas (the only official civic pizzas) from hand-kneaded dough (no rolling pins!) that should be cajoled into a disk not to exceed 13.8 inches across and baked in a wood-fired brick oven. The cornicione must not rise above four-fifths of an inch.

For all their pizza purism, Da Michele’s pizzaioli seem to revel in flouting conventions. Rather than extra virgin olive oil, they use cheaper vegetable oil; instead of mozzarella made from the milk of water buffaloes, they use a cow’s milk alternative, which they insist maintains its soft consistency better in the intense dry heat of the ovens. Da Michele’s amoeba-like pies overflow the plate, and you’re not sure whether to eat them or keep them as pets.

* * *

The Dalai Lama walks into a pizza shop and says, “Can you make me one with everything?”

Of all the chefs dreaming up ethereal Neapolitan pizzas, none is as learned as Enzo Coccia. His pie-making academy in Naples’ affluent Vomero district lures pilgrims from great distances, all seeking red sauce enlightenment. Coccia disciple Daniele Uditi, of Pizzana in Los Angeles, says no other chef is so analytical: “Enzo thinks about pizza from an intellectual perspective. He changed the way modern pies are made and brought respectability to the craft.”

Quiet and professorial, Coccia, who’s 58, has dabbled in chemistry, anthropology and physics to better understand what he calls the “delicate dance” of assembling a proper Neapolitan pizza.

“I can see a pizza from across a room and diagnose what is wrong with it,” says Coccia. La Pizza Napoletana, the handbook he co-wrote in 2015, bubbles over with sprightly entries such as

“The quantity of heat transferred from the floor of the oven to the pizza is given in the equation:

Qcond = k A (Tb – Timp).”

Coccia began working at his family’s trattoria near the Napoli Centrale train station at the age of 8, and he now runs the school and two pizzerias, most notably La Notizia. He launched the city’s “new pizza” movement in 1994, becoming the first pizzaiolo to experiment with dough using a variety of flours and lengthy proving times. Among the surprising flavor combinations on his more avant-garde pies: eggplants and mint burrata; broad beans and asparagus; and lemon, licorice and zucchini pesto. (Pepperoni, an American invention, is a Naples no-no.)

Yet, he cautions, “A pizzaiolo should not combine more top-of-the-line garnishes than is absolutely necessary. A terrible pizza chef who uses excellent raw materials will produce terrible pizzas, and an excellent pizza chef who uses terrible raw materials will also produce terrible pizzas. Nothing is more critical than the quality of ingredients.”

Except maybe the baking chamber. Coccia notes that Neapolitan pizza ovens have unique thermal properties, incorporating three means of heat transfer: conduction, convection and radiation. The brick floor cooks the pie by direct contact, or conduction. The curved interior circulates hot air throughout the chamber (convection), and heat absorbed into the masonry radiates from the dome.

Radiant heat is what actually cooks the pizza, and because the heat waves come from so many angles, the temperature of the cooking surface isn’t uniform. “Every oven has hot spots,” Coccia allows. “The pizzaiolo must be familiar enough with an oven’s quirks to eye a pie and know where to move it next. With a single pizza, no problem. But when four or five bake at once, anyone less than a master is likely to cremate them all.”

Like many restaurants in Italy, the pizzerias of Naples were hit hard by the pandemic. Many parlors survived the three-month spring lockdown on the back of Cassa Integrazione, a government program that covers up to 80 percent of employees’ wages for companies that apply and are accepted into the relief scheme. The plight of the pizzerias was also partly alleviated by a “heal Italy” decree that suspended loan and mortgage repayments for companies and families, thanks to state guarantees for banks, and increased funds to help firms pay laid-off workers.

Coccia reports that during the first Covid-19 wave, the money brought in by carryout—deliveries were prohibited—wasn’t even enough to cover his staff’s salaries, let alone his overhead costs. He estimates that his business was down some 75 percent. The outlook got rosier over the summer, but on October 25, after coronavirus deaths in Italy had tripled in a month, the state imposed a strict curfew: Restaurants were forced to close at 6 p.m. and could offer only takeout.

The pizzas that Coccia concocted for home delivery during the pandemic’s second wave require lower oven temperatures and longer cooking times, making for a slightly drier pie. “We will continue with home deliveries and takeaway,” he says, “but always giving the priority to the customers at the table.”

I ask Coccia to name a Neapolitan pizzaiolo at the pinnacle of his profession. “Attilio Bachetti,” he says without hesitation. “He makes the lightest, most digestible pizza there is.”

Bachetti, who shapes the pies at Pizzeria Da Attilio, is smiling but ascetic, a lovable obsessive whose devotion to pizza is complete. The son of a pizzaiolo who himself was the son of a pizzaiolo, he began his apprenticeship at age 6. He’s now 56.

Da Attilio is an unpretentious gastronomic shrine smack in the middle of the lively Pignasecca market. You are greeted at the door by Maria Francesca Mariniello, daughter-in-law of the Attilio Bachetti who opened the joint in 1938 and mother of the Attilio Bachetti who presides over it now. The walls are blanketed in press clippings, celebrity photos and framed napkin doodles, many of which picture the chef molding his precise and studied creations.

Bachetti says the secret to Da Attilio’s airy crusts is “little yeast, lots of time.” His signature dish is the Carnevale, a baroque fantasy of tomato, sausage and fior di latte (flower of milk) mozzarella that sports an eight-pointed crust folded around sweet ricotta. His other showstoppers: pizza giardiniera, also eight points packed with grilled mushrooms and sautéed vegetables; pizza cosacca, a marinara-margherita hybrid (mozzarella out, grated cheese in); and bacetti (little kisses), spiral rolls of dough bursting with ricotta and provola and perfumed with nutmeg and black pepper.

The precision of Bachetti’s hand movements is something to behold. He’ll grab a ball of dough, bloated from a two-day prove, and slap it onto a lightly floured marble countertop. Pressing his fingertips gently from the center of the bloat toward the edges, he gingerly massages, punches, stretches and turns it back on itself. He spreads a few tablespoons of tomato sauce over the dough, crowns it with cheese and herbs, drizzles on olive oil, and pulls the edges of the crust taut over the small, round palette of a palino, a long-handled, stainless steel turning peel. Then he slides the impasto into the glowing mouth of the oven and gently rotates the pie while it cooks. After a minute, he centers the palino under the crust and lifts it slightly to give the underside a final char, a technique known as doming.

On the journey between plate and mouth, the bouncing strings of molten cheese seem to be alive. They’re not, of course, though technically the crust was before it was browned.

* * *

Before I arrived in Naples, Katie Parla, author of Food of the Italian South, warned me, “Once you’ve been to Pepe in Grani, you’ll never be able to eat pizza anywhere else ever again.” For three years running, Pepe in Grani—the showplace of pizzaiolo Franco Pepe—has been voted Italy’s finest pizzeria in the 50 Top Pizza Guide, a prestigious list judged by Italian culinary heavyweights.

Los Angeles chef Nancy Silverton, whose Pizzeria Mozza is North America’s pre-eminent sourdough establishment, likens Pepe’s pies to perfectly roasted marshmallows. “The perfect marshmallow is not one that goes right into the flame and chars,” she says. “It takes patience to be near a flame and get that beautiful caramelization. Franco has achieved perfection through his mastery of pizza-making. It feels almost like he invented pizzas and the rest of us are just copying him.”

Deliberately working outside Naples and the reach of the Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana, Pepe excels by breaking all the laws governing Neapolitan pizza. He fashions outlaw pies that triumph despite everyone’s worst wishes for them. On this mild Mediterranean evening, Pepe lopes through his restaurant looking happy, proud, at peace. Pepe in Grani is housed in a restored 18th-century palazzo in the old Roman hill town of Caiazzo, located about an hour or so northeast of Naples. It’s a block away from his grandfather’s bakery, where there were no recipes, scales, clocks or machinery.

Pepe’s family cooked a occhio, guessing at a glance. “Year after year, I watched my father construct dough from scratch,” he says. “He never wrote anything down for me. He didn’t have to. I know instinctively how dough should feel. Day by day, to suit the weather and humidity, I change the mix, the leaven times, the quantity of yeast. I never refrigerate the dough. Tactile experience teaches you it is wet and asking for flour, when it’s stiff and needs to be bathed, when it’s ready to be stretched and no longer wants to be touched. Mechanical technique will not help. Dough is like a baby: You must listen closely to grasp what it desires.”

Evidently, what the dough desires is to stay home. Pepe is the most noteworthy holdout against takeout and delivery. Since nearly all his diners are out-of-towners, he decided to cease operations until the restaurant could reopen. “The distance that delivery would have to cover is way too long for enjoying the product—it would be ruined,” he says. “I don’t believe the pizza would ‘hold.’ My pizzas can only be eaten on the spot.”

Pepe credits much of his success to his flour, some of which is milled from an indigenous grain last grown in the region in the 1950s. He rejects the commercial flour decreed by the AVPN. “To help preserve customs and established practices, I source ingredients almost exclusively from local suppliers,” he recounts with terse modesty. The cheese is made and the onions grown for him alone. He collaborates with small farms to revive disappearing heirloom species such as the pomodoro riccio. Vernino genuine, the extra virgin olive oil, is produced from age-old groves a couple of miles away; the oregano comes from the nearby town of Matese; the sausage, from a breed of black swine that, some 20 years ago, pig farmers in the Caiazzo area brought back from the brink of extinction. “I change the future of pizza by looking backward,” says Pepe.

A Neapolitan pizzaiolo is only as good as his margherita, and Pepe’s are otherworldly. His margherita sbagliata—roughly “margherita gone wrong”—is a playful deconstruction of Raffaele Esposito’s 19th-century pie. Rather than spoon tomato sauce on a cheesy crust and bake it together, he bakes just the cheese and the crust. When the white base emerges from the oven, he embellishes it with a basil reduction and a few graphic lines of tomato purée—a marriage of hot and cold, cooked and raw. You get the classic margherita flavors turned upside down.

Pepe treats many of his specialties the same way, placing individual toppings—fig jam, mortadella with crème fraîche—upon the heated pies. Parla observes: “Every pizza is the fruit of thoughtful planning, planting, producing and harvesting which respects the rhythms of nature and transmits flavor, which will simply change the way you think about food.”

* * *

If there’s a millennial chef capable of taking Neapolitan pizza to the next level, it may be Ciro Oliva. The 28-year-old behind Pizzeria Da Concettina ai Tre Santi has a boyish, uninhibited manner and a spontaneous, beaming smile. His great-grandmother Concettina began selling fried pizza in the same building in the earthy Sanità section of the city. “The entire shop consisted of an oven and a window to hand out food to customers on the street,” he says.

Order Oliva’s decadent 12-course tasting menu and he’ll serve you himself, with elaborate explanations of each experimental dish. The novelties run the gamut from pizza bagels to butter, salmon and caviar-studded pies to “The Memory of Sunday,” a hodgepodge of tomato, parsley and creamy clam sauce. “No forks or knives required,” Oliva counsels. “Eat with hands, always.”

His response to the lockdown restrictions was to devise four different boxed pizza kits: the standard margherita; salami; deep-fried; and anchovies and black olives. The DIY instructions come with a caveat: The premade dough should rise for no more than 48 hours. Let the dough prove too long, Oliva warns, and the yeast expends its gas-producing energy, leaving you with a dense, deflated pie.

He’s a generous soul who genuinely cares about fellow Neapolitans in need. He pays the cost of English lessons for neighborhood kids so they won’t be tempted to join the Camorra. For about $3, Oliva will provide a pie to anyone who can’t afford to buy his or her own. If the customer is broke, he’ll defer payment for eight days, a longstanding Neapolitan practice called pizza a otto, or eight-day pizza.

The citizenry of Naples lives close by a volcano that’s both a memento mori and an index of the human condition. In a city with a predilection for light and shade, optimism coexists with the sober reality of death. During this era of Covid, when time can seem suspended, perhaps no Neapolitan custom is as poignant as the “pizza sospesa” (the suspended pizza), a form of generosity that involves eating one pie and paying for two, leaving the other for a less fortunate stranger. “No one should be denied a pizza,” Oliva says. “It’s the food of solidarity.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/fa/e1fa4450-5399-4761-a50e-acd474dce65e/mobile_-_mar2021_c05_pizza.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/8d/198d7111-d3e9-4060-b615-f12c44f479b1/opener-1.jpg)