On the Cheese Trail in the Pyrenees

Make a fuss in the road and someone will appear. Spit out some gibberish about “fromage a vendre,” and that should do it. You’ll get your cheese

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120607092026CheeseDeBrebisSMALL.jpg)

For the past eight months, for a variety of environmental reasons, I have abstained from eating any cheese—but last week I went tumbling off the wagon. I couldn’t help myself any longer. For the Pyrenees, I’ve discovered, is a cheese-producing district about as moldy and musky as they get outside of Roquefort. Cows and sheep seem to outnumber people, grazing on the hillsides in vast herds and clogging the roads as villagers drive them into the high country for the summer—an annual occasion for festivities and celebrations in many villages. These are the animals that have indirectly caused the extermination of bears and wolves from most of the nation. About two dozen brown bears do still tiptoe through the woods in the Pyrenees, leery of gun-toting shepherds, but mostly they have been replaced by milk-making grazers. So you can bitterly hold your grudge and boycott all things milk-related, like I periodically do, or go tasting.

Villagers drive a flock of more than 2,000 sheep into the high country of the Pyrenees, where the animals will graze for the summer. Photo by Alastair Bland.

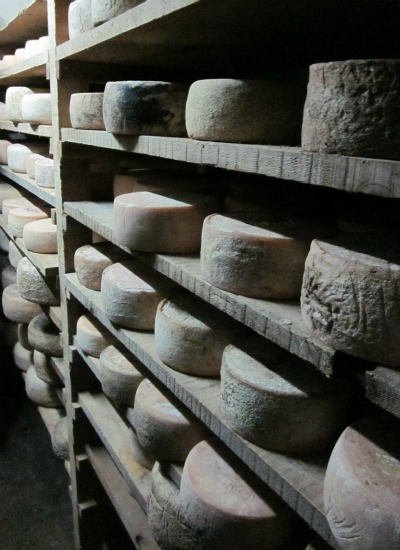

In Gez, on the road from Argeles-Gazost to the Spandelles pass, a small sign midway through the village tells passersby of fromage in the vicinity. Knock on the nearest door, and if that fails to draw a response, make a fuss in the road and stomp your feet, and someone will appear. Spit out some gibberish about “fromage a vendre,” and that should do it. Someone will lead you into the cool damp cellar, quiet and regal as a chapel and home to a hundred-something wheels of cheese—and never illuminated with more than a dim fluorescent bulb.

In the damp and darkness of a cellar, creamy wheels of sheep cheese age into fragrance and maturity. Photo by Alastair Bland.

Some of the wheels are fresh and white as snow, but not yet for sale. Others are covered in greenish fuzz—unintended mold that will be scraped from the rind before long. Still others are crusty, brown, veined inside with the desired Penicillium mold and smelly—and ripe for purchase. Ask for some sample tastes, then buy a hunk for the hills. (This is your last chance for fuel as you ride into the wilderness.) And in Poubeau, along highway D-76 on the east side of Col de Peyresourde, the village fromagerie sells a tomme cow cheese, made on-site from a dozen heifers. Follow the signs, knock on the door, and if no one answers, go bug the neighbors. You’ll get your cheese. And just uphill from Luz-Saint-Sauveur, en route to the spectacular Luz-Ardiden summit, the Ferme de Cascades, operated largely by WWOOF workers (world wide opportunities on organic farms) makes and sells goat cheese. Their hours are odd—just 4 to 6 p.m.—so plan accordingly. The cheese, including creamy day-old chevre and old crusty bricks, is a bit expensive for the area (20 Euros a kilo, or about $10 a pound), but it’s organic, it’s tasty and—as good goat cheese should—it really smells and tastes like a goat. Down in the foothills in the town of Tilhouse, another fine and friendly cheese-making operation is La Ferme de Baptistou. Home to 100-something sheep, the farm also buys cow and goat milk and makes several blends, all up to par with French cheese-making standards (much like European wine is regulated) and classed as Pyrenees tomme. Follow the signs reading “fromage de brebi” (sheep cheese).

Where milk comes from: At La Ferme de Baptistou, pumps draw the milk from each sheep in just minutes. The cave is just down the hallway---and for the author a sheep's milk coffee would be had at a picnic table just down the road. Photo by Alastair Bland.

For the cyclist, it’s a heartbreaking descent down a steep hill to the farm (I had just climbed about 800 feet out of the Arros River valley, all my gear doubled in weight by a night of rain), but the experience is well worthwhile. Ask to see the cave, and they’ll show you inside. Ask for a few samples, and they’ll taste you through young and old cheeses of goat, sheep and cow. I chanced to arrive just before milking time, and a friendly farm apprentice in training named Julien allowed me to watch the operation and even sent me away with a spot of milk for my coffee. It was my first sheep milk cafe au lait.

Not into cheese? Then tour the local morning farmers markets for other goodies—Thursday in Arreau, Wednesday in Bareges, Tuesday in Argeles-Gazost, Sunday in La Barthe-de-Neste, to name several. Chantecler apples, white asparagus, pre-baked beets and farm-fresh eggs are my staples of living. You might also run into Geert Stragier, who keeps court at multiple farmers markets—including Thursday morning in Arreau. He is not a farmer or an artisan of any sort—just a merchant—but he sells what few else do in this wine-oriented culture: about 50 Belgian beers. Want some locally brewed beer? Of the 400-plus craft breweries in France, three, I’m told, dwell in the Pyrenees. One, L’Aoucataise, is based in Arreau—a homebrewing-size setup in the rear of a small cheese-and-wine boutique. Five year-round staple beers in bottles, including an amber beer, a blonde beer, a honey beer and a beer with no alcohol, make up the repertoire of owner and brewer Christian Arzur, who told me that wine sales are dropping nationwide as artisan beer sales slowly climb. The shop offers beer tastings during the summer months, if you arrive with a group large enough that Arzur isn’t left with several half bottles. Step inside the shop, located across from the market plaza, to inquire.

Geert Stragier with his selection of Belgian beers at the Thursday Arreau farmers market. Photo by Alastair Bland.

If you just can’t get enough of the hills, then stay in the mountains—but forget about the trophy climbs of the Tour de France and consider some lesser known but just as grand ascents, like Col de Spandelles, Col de Couraduque, Port de Boucharo and Port du Bales. By the numbers, these ones—oh, never mind meters for a while. Just enjoy the ride. I climbed Bales from the south side. The north side is absurdly steep and a terror just to ride down—but on top was a view about as mighty as any I’ve seen in Europe. To the north and a mile below, the expanse of France lay before me. Out there, on that brown distant landscape, was the Armagnac region, the Landes forest, the lovely Perigord farther north and the posh wine-making castles of Bordeaux off to the northwest. England could not be seen, hidden beyond the curved surface of the Earth, but I almost swore I could see the tip of the Eiffel Tower.

This just in: Want a hot deal on Parmesan cheese? A correspondent of mine who lives in the north of Italy (Aunt Bobbie) reports that in the city of Ferrara, cheese houses damaged by the recent earthquake are selling off their quake-damaged wheels of immature Parmesan at about 25 percent off normal prices. Most families, Bobbie reports, are snagging 10 kilos at a time. Better get there quick.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)