The Ghost Wineries of Napa Valley

In the peaks and valleys of California’s wine country, vinters remember the region’s rich history and rebuild for the future

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Freemark-Abbey-631.jpg)

Atop Howell Mountain, one of the peaks that frame California’s wine-soaked Napa Valley, the towering groves of ponderosa pines are home to one of the region’s legendary ghost wineries. Born in the late 1800s, killed off by disease, disaster, depression, and denial in the early 20th century, and then laid to solemn rest for decades, La Jota Vineyard — like its countless sister specters found throughout the region — is once again living, breathing, and making world-class wine. And for those who care to listen, this resurrected winery has plenty to say about everything from America’s melting pot history and the long-celebrated quality of West Coast wine to strategies for sustainability and using the power of story to boost sales.

“This is the hot-spot in Napa now, Howell Mountain,” explained Chris Carpenter, head winemaker of La Jota, just one of many resurrected ghost wineries in the Napa Valley. “These guys knew it in 1898,” said Carpenter, referring to the mountain’s optimum grape-growing conditions. “This is 110 years later, and we’re still doing it up here.” Originally founded by German newspaperman Frederick Hess, La Jota rose to prominence at the turn of the century, winning a bronze medal at the Paris Expo of 1900 and then gold at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904. “This is way before the Paris tasting we hear so much about,” said Carpenter, referring to the blind tasting of 1976 where California wines beat out French entries and opened the door for wines from around the world.

Aside from reminding the world that Napa’s juice was beloved 100 years ago, La Jota and other ghost wineries offer vivid lessons about bygone eras. “One of the things I find fascinating is the international flair,” said Carpenter. “It was overseen by Germans, designed by Italian masons, and built by Chinese laborers who were working the nearby quicksilver mines. And they were making French-style wines that were selling to any number of Anglos. There’s a lot of Americana in all that history.”

But the forces that built the old wineries weren’t as strong as the attacks that brought them down. Many early Napa Valley wineries were first decimated in the late 1800s by the vineyard pest phyloxerra. (Ironically, the disease’s previous scourge of Europe actually helped fuel the Napa boom.) Then came the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906, which literally smashed warehouses full of inventory, followed by the economically stressed times of World War I. But the crushing blow was, of course, the 1919 passing of the Volstead Act, which banned all manufacturing, sales, and drinking of intoxicating beverages.

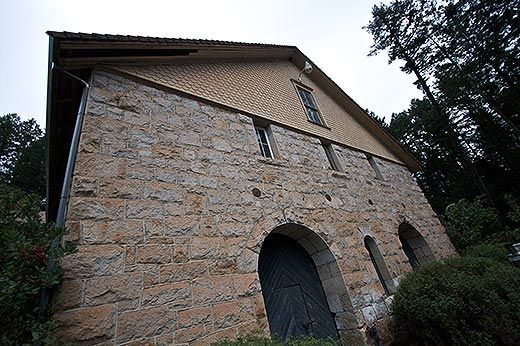

“Prohibition really kicked the industry in the butt,” explained Ted Edwards, winemaker at Freemark Abbey, a fully functional ghost winery located on the valley floor just north of St. Helena. “It was hard to make a comeback.” With vineyards ripped out and the valley widely replanted in fruit and nut trees, Napa’s wine did not make a prominent return until the 1960s, when wineries such as Freemark Abbey — originally founded in 1886 by Josephine Tychson, arguably the first woman winemaker in California — were reborn, with many folks setting up shop in the same stone structures that were used decades before.

Compared to the Old World wines of France and Italy, Napa Valley remained a New World backwater until the famed Paris Tasting of 1976, when Stag’s Leap took home top prize in the red category and Chateau Montelena won the whites. But Chateau Montelena’s history goes back to 1882, when state Senator Alfred Tubbs, who had been romanced by wine during his travels through Europe, purchased about 250 acres of land near Calistoga, brought in French vineyard consultants, and erected a modern castle to house his winery. During Prohibition, the property was turned over to peaches and plums, and it wasn’t until Jim Barrett bought the property in the late 1960s — when, in his words, “it was just ghosts and spiders” — that wine again took center stage. Today, visitors can sip Montelena’s chardonnays, zinfandels, and cabernets amidst the redwood beams and locally quarried stone of the original construction and, if they look hard enough, can find a tattered, hand-written letter posted on a hallway wall. Writing to his French-born winemaker Jerome Bardot, Senator Tubbs requests that a case of 1888 vintage be sent quickly down to San Francisco, asking for “fair-average samples” and reporting that “the red is in most demand now.”

With Napa Valley’s modern quality finally cemented in 1976, the resulting 30-plus years have witnessed an explosion of new wineries, such that setting oneself apart from the pack requires more than just fermenting great grape juice. Many vintners are turning toward sustainability and storytelling to establish their brand, and taking direct cues from ghost wineries to do so. No one embodies this two-pronged push better than Hall Winery, located just south of St. Helena on Highway 29, Napa Valley’s main artery.

First planted in the late 1870s by New England sea captain William Peterson, the vineyard and two-story winery — whose construction was completed in 1885 — fell victim to phyloxerra in the 1890s, was sold in 1894 to German immigrant Robert Bergfeld (who chiseled Peterson’s name off of the façade), and was then bought in 1906 by Theodore Gier, who is rumored to have gone to prison for selling liquor illegally during Prohibition. During World War II, the winery — which had then become the Napa Valley Co-op, where local growers could come to make their wine — was enclosed within a massive redwood shed and cut off from the world. But it’s about to see the sunlight again, as owners Craig and Kathryn Hall plan to dismantle the redwood shed piece-by-piece and reveal the stone structure for all to see. “This will be the focal point,” explained the winery’s Bronwyn Ney. “It’s such a beautiful historic building that has such a signature in the valley and you would never know it was here. We’re going to give it back to the Napa Valley.” Beyond that, Ney, opining that “wine is about celebrating stories,” explained that Hall Winery’s ability to connect with customers via its historical roots will only make popularizing the relatively new label all the easier.

But it’s not just about telling tales, says Ney, it’s about learning from the past too. Across the lot from the old winery is the new one, the first LEED Gold certified winery in all of California. The model for sustainability employs such novel techniques as allowing gravity to move the wine rather than pumps and farming the vineyards organically without unnecessary chemicals — both practices used out of necessity by the ghost wineries of yesteryear. “The more advanced you become,” admitted Ney, “the more back to basics you get.”

With so much to learn from the past, it’s no wonder that the resurrections continue. Few appreciate the ghost winery lore as much as Leslie and Richard Mansfield, who are in the midst of reviving the Franco-Swiss Winery, located amidst the oak trees, stags, bobcats, coyotes, bald eagles, and mountain lions of Conn Valley, a few miles east of Napa. “We are the last ghost winery in the valley,” claimed Leslie Mansfield, who wrote one letter per month for three years to the property’s owner until he finally relented in 2008 and sold them the winery, which which was founded in 1876 and made 100,000 gallons annually during the 1880s. “Napa really wants to preserve the history that it has, and this is still in the historic context of what it was. You could be back in the 1880s here.”

The winery, which eventually became a perlite factory, is now dilapidated and needing much renovation, but its spirit is palpable, symbolized in the painted, circa-1876 sundial that’s still visible on the exterior wall. And, according to the Mansfields, it also puts the ghost in ghost winery. One night after enough wine, Richard and some of his friends went down to the winery and called out the name of Jules Millet, a man who was murdered on the property by a disgruntled worker in 1882. Millet did not respond, but the next night when Leslie was home alone, the six flashlights that had been used in the winery all exploded, even bending a C battery in half. “I didn’t believe in ghosts before,” said Leslie, “but I do now.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.