The Hunt for a Bottle of Asturias Cider and the Stories of More Drinks From Northern Spain

In this part of Europe, a glass of rioja is nice, but nothing beats apple cider, a way of life

Manuel Martinez, bartender at the family-operated La Figar Bar in Nava, pours a glass of cider. He stood by to provide pour after pour until the bottle was finished. Photo by Alastair Bland.

If you have lemons, you make lemonade, and if you have honey, you make mead, and if you have Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc grapevines in soil so rich and sweet that you could almost eat it with a little salt, you make Chateau d’Yquem.

And if you have apples, you make cider—and so the people do in Asturias, in northern Spain. Apple trees grow prolifically on the rolling green hills here, many stubby as shrubs, others as large and ragged as oaks. Many grow randomly, as scattered as the sheep and cows, while other property owners tend checkerboard orchards of trees. Just about every household has several, and behind many a roadside bar—usually sub-headed as a “sidreria”—grow trees used to make the house apple cider, which is often served from the spigot of a barrel.

Cider is a thirst quencher here, and it’s a way of life. In the fall, thousands of people participate in the harvest, sending the fruit to about two dozen local commercial producers (many other unregistered sellers bottle cider at home) where the fruit is crushed, the juice fermented and the drink eventually released in wine-sized bottles. Essentially every bar and restaurant in the area serves cider, and here is where one must go to experience cider as Asturians do—and to experience what a lot of fuss Asturian bartenders and patrons put up with for a bottle of some local farmhouse tipple. The bartender makes a grand show of popping the cork and pouring the cider from overhead into a glass held at waist level. The first splashes generally miss and hit the floor before he finds the stream. He fills the glass only about a quarter full, and the recipient must be standing by to drink immediately, to enjoy the bubbles created by the aeration (the cider here is not carbonated). The customary fashion is then to dump out the last splash, a gesture that supposedly freshens the glass for the next person (the presumption is that people are sharing glasses). Want more cider? Somebody, if not the bartender, must go through the pomp and circumstance again, often in a designated corner of the bar, and by the end of a 750-milliliter bottle, about a third has been spilled. I can only presume Asturian bartenders don’t wear their best shoes to work. Relax over a beer, then get back to work with another splash-dance of cider.

Asturias cider is protected by a Denomination of Origin status, the European Union system of guidelines that lays out laws for the making of regional products like cheese, wine, beer and breads. For cider to wear the proud name of Asturias on its bottle, it can be made using only 22 certain varieties of apples, though more than 250 grow in the region. Most producers use an unspecified mélange of apples, generally five or six varieties, and the wide range of possibilities allows for a great diversity in Asturian cider—though to some degree it’s all roughly the same: usually dry and a bit tart, about 6 percent alcohol by volume, with smells and flavors suggestive of hay and barnyard. Called sidra natural, it’s still as a swamp, and about as green and cloudy, too. It’s also delicious.

Sidra natural, as it’s called in Spanish, is simply apple juice, fermented, barrel aged and bottled without carbonation. This particular bottle pulled the author through an especially rigorous day of cycling over Puerto de Tarna. Photo by Alastair Bland.

In the town of Panes, I loafed around the streets for several hours, looking at the displays of ciders carried in every bakery, butchery, grocery store and gift shop—but nowhere, unfortunately, was there a place to taste through a lineup of ciders by the pour; that is, you’ve got to buy the whole bottle and be ready to get your feet wet. I visited the fish market—Huly Pescaderia, it’s called—and talked with the owner, named Julian. Our conversation diverged quickly from farmed Norwegian salmon to cider, for Julian said he makes his own. He invited me, in fact, to a cider party that night in his home, but I had other obligations. Julian doesn’t sell his cider but still abides by E.U. guidelines in making proper Asturian cider. His cider includes (he wrote these names for me) Francesca, Berdalona, Solalina and De La Ruega apples—and it takes about seven pounds of fruit for a liter of juice. Julian said he even ages some cider and has tasted some phenomenal stuff stashed, forgotten then found more than a decade after the cork went in.

But cider is generally had fresh, with the first bottles opened the May after the fall harvest—meaning the 2011 vintage is just hitting the floorboards—and things are about to get crazy. Because each July, the Nava Cider Festival draws thousands of people to the small town of Nava, just west of the Picos de Europa. This year, from July 6 to July 8, the population of 3,000 will boom for a weekend in the main plaza (where a large mural depicts a man pouring cider from overhead), with lectures and talks and demonstrations preceding the free tasting on Saturday. Sunday always includes a pouring competition, in which competitors show their skills in pouring cider from great height, with as little as possible splashed to the floor. I visited Nava, and stopped at La Figar Bar, a dark but cozy wood place with an old bar, animal mounts on the wall and cider festival memorabilia occupying almost every available surface. Bartender Manuel Martinez opened me a bottle of Asturias Foncueva Sidra and showed me the way the pouring is done—and with no annoyance that he had to get his shoes sticky on my account. He took me to the rear parlor, too, to show me the barrel in the wall, containing cider in bulk (no need for a whole bottle) and served me a portion from the spigot, glass held five feet from the tap (he admitted that the barrel is “falso,” fed by a tube from a keg behind the wall).

The mural above the festival plaza in Nava depicts the magnificent image of a champion cider server in action. Photo by Alastair Bland.

The next day was Huelga General, June 18, when everyone in Asturias does no work at all and instead stands on the streets in the drizzle, celebrating the holiday with their feet to the curb and watching the traffic go by. Not even the cafes were open, and I pedaled on empty the fastest way out of the province that there was—over a mile-high pass called Puerto de Tarna. Every restaurant was closed along the way, and I was nearly crazed with hunger by 2 p.m., when, halfway up the climb, I pounded on the door to a tavern and talked my way into buying a bottle of cider. I found a nearby bench and fueled up. It was gold and spritzy and would have done well with a blue cheese—but what I would really have almost killed for is a fig tree. The cider, with 6 calories per gram of alcohol and a few more in the residual apple sugar, pulled me through, over the pass and into the region of Castilla y Leon, where the towns were operating and the stores open. Now about 3,000 calories in the hole, I found a shop in Riano, 20 miles below that horrible pass. It was 6 p.m. I had gone all day without food, thanks to that strange Asturian holiday on which tourists are left to starve. I bought walnuts, beets, an avocado and a beautiful melon—and I asked for a bottle of “sidra natural.” The lady shrugged and said sorry.

“For cider,” she advised, “you should really go to Asturias.”

What Else to Drink in Northern Spain

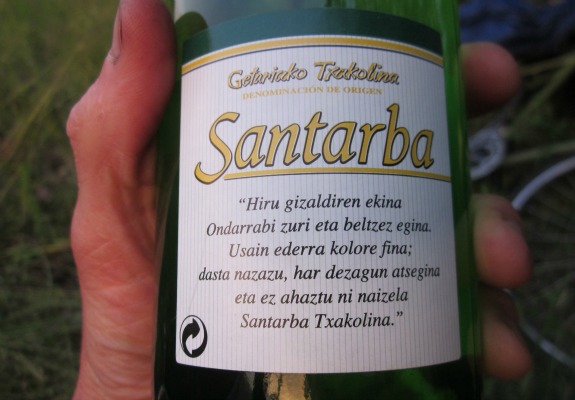

Txakoli. The white wine of the Basques, txakoli (say cha-kho-lee), or txakolina, is spritzy and greenish, with an herbal grassiness and easy-drinking flow that gains it a reputation among some as a simple wine, not to be regarded seriously like the stodgy old bottles of Bordeaux or the other highbrow districts. Others revere it, handle the bottles like small babies, and charge 8 Euros or more for a bottle. Yikes. I have sampled several. I enjoyed each, especially the Santarba Txakolina, of 11 percent alcohol, with a mint-lime flavor and a cool aftertaste of spearmint, and very refreshing in the horse pasture where I drank it before bed.

Rioja. Grown below the southwest slope of the Spanish Pyrenees, Rioja is often red and made largely of Tempranillo grapes. It tends to be heavyset, forceful and fruity, with powerful tones of raspberry and cherry. I’ve been seeking out the 2005 vintage for no reason other than that 2005 was a good, and eventful, year for me. I was in Spain that fall, watching the grape harvest. It was also one of the driest years in history on the Iberian peninsula, which was interesting. Goats, I recall, were ravenously sifting through the gravel in search of grass sprigs and chasing me in the hope of eating my dirty laundry. And that was also the trip which ended in a crash, dumping me on the asphalt near Valencia with a broken wrist and my splintered collarbone sticking through the skin of my neck. Wine is an experience of time and place, and the 2005 Rioja takes me back to a good one.

Say what? Never mind. Just drink. The language is Basque, and the wine is txakoli, the main white wine of the Basque country of northern Spain and southern France. Photo by Alastair Bland.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)