When Cane Juice Meets Yeast: Brewing in Ecuador

The sugarcane trail takes the author across the Andes, into liquor distilleries and from juice shack to juice shack as he pursues fermented sugarcane wine

A juice vendor near Paute, just east of Cuenca, grinds sugarcane—the main source of sugar and alcohol in Ecuador—on a busy Sunday afternoon. The sweet and delicious greenish-blue juice runs out a spigot into a bucket and is sold by the glass or bottle. Photo by Alastair Bland.

First, there was sugarcane juice. Then came distilled cane liquor, dribbling out of a steel pipe.

And somewhere in between was the stuff I was interested in: fermented sugarcane juice touched by the ethanol-making labors of airborne yeasts and containing 8 to 9 percent alcohol by volume. But fully fermented cane drink with 8 or 9 percent alcohol by volume is not easy to find in Ecuador. I have been on the lookout for this stuff since Day 1 in Ecuador a month ago, when I began seeing extensive sugarcane fields, and I have yet to land a used plastic soda bottle filled with the beverage. The clear liquor—90-proof stuff, or thereabouts—whether commercially bottled or sold out of kitchens in Inca Kola bottles, is easy to find. Ditto for the raw, algae-green juice, which comes gurgling out of hand-cranked cane grinders on street corners in almost every town and is sold for 50 cents a cup.

The only way to go from raw, sweet juice to hard, throat-raking liquor is to ferment the juice’s sugar using yeast, then distill this sugarcane “wine” into the hard stuff. In Vilcabamba, at last, I knew I was getting close to this almost theoretical product when, in a grocery store, I found homemade vinagre de cana. Vinegar, like hard booze, is a product derived directly from fully fermented juice, or malt water like beer wort. So a local household, it seemed obvious, was engaged in the cane juice industry.

The presence of homemade sugarcane vinegar means that fermented cane juice cannot be far away. Photo by Alastair Bland.

“Who made this?” I asked the clerk.

She directed me to a home several blocks away where, as she said, a man fermented cane juice and sold a variety of cane-based products. I cycled over, but the man’s wife answered and said they only had distilled liquor, which may be called punta or traga. I bought a half liter for $2 after making sure that it was safe to drink. I mentioned the tragic scandal in 2011, when dozens of people died from drinking tainted distilled alcohol. “We drink this ourselves,” the woman assured me.

Before I left she said that in the next village to the north, Malacatos, many people grew sugarcane and made traga and that I could find fermented juice there. But I had already done the Malacatos juice tour the day prior, while riding through on my way to Vilcabamba from Loja, without luck. At every juice shack I visited, the proprietor said they had none but that they would make some overnight and that I should return in the morning. They all spoke of a drink called guarapo—fermented cane juice.

This sounded almost right—but not quite. Because I know from experience making beer and wine that it takes a solid week or more for a bucket of fruit juice or sugar water to undergo primary fermentation, the vigorous bubbling stage that turns 90 percent of a liquid’s sugars into ethanol. Brewers and winemakers cannot make their products overnight.

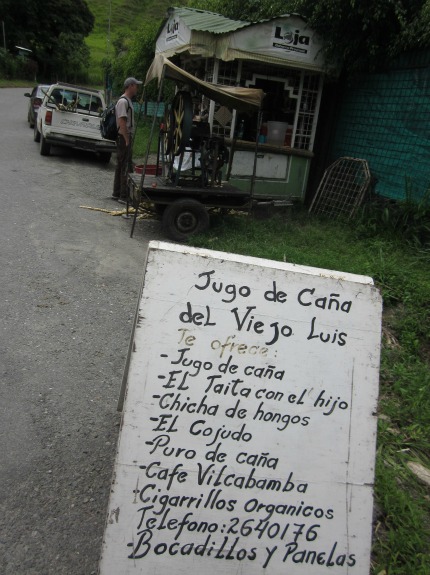

The sign by the juice shack of Viejo Luis, in Vilcabamba, advertises several of the many products that originate from sugarcane. Photo by Alastair Bland.

I learned more about this matter in Vilcabamba’s eastern outskirts, just outside the entrance to the village zoo. Here I found a woman selling cane juice under the business name “Viejo Luis,” who, it seemed, was her husband. I bought a liter of juice, then was treated to a taste of guarapo fermented for one day—a sweet-and-sour rendition of fresh cane juice. At the risk of sounding crass, I got straight to business: “Does this guarapo have alcohol?” I asked. Yes. “How much?” A tiny little bit. “I want more.”

To better explain myself, I asked the lady to tell me if this was correct: “First, there is juice. Then, you ferment it to make alcohol. Then, you distill it to make liquor.” She nodded and smiled with a genuine sparkle, pleased, I think, that I recognized the labors of her business. “OK, I want the middle juice—the juice with alcohol. Not fresh juice, and not punta.” She nodded in understanding and said that if she were to leave this one-day fermented guarapo for another week, it would contain as much alcohol as a strong beer. She even said she would sell me a liter for $2—if I came back the next weekend.

This wasn’t possible—but she did have another fermented product ready to sell—chicha de hongos. That translates into, roughly, “fruit beer of fungus.” She poured the thick, viscous drink through a sieve and into my plastic bottle. I had a taste immediately and complimented the rich and buttery green drink, tart like vinegar, and teeming with an organism she said was tivicus but which most literature seems to present as tibicos. This fungus-bacteria complex turns sugary drinks sour, thick and soupy and allegedly provides a wide range of health benefits. She assured me it was an excellent aid for facilitating digestion.

A pinch of baker’s yeast will bring to life a half liter of sugarcane juice, producing “wine” in about a week. Photo by Alastair Bland.

Meanwhile, I hatched a plan. I took my liter of Viejo Luis’s cane juice to the village bakery. “Can I have just a tiny, tiny, tiny pinch of yeast?” I asked in Spanish. The young man came back with a sack the size of a tennis ball. “That enough?”

Plenty. I took the gift and, on the curb by the plaza, sprinkled a dusting of yeast into the bottle. It came to life overnight. I reached out my tent flap in the morning and unscrewed the cap. It hissed as compressed CO2 exploded outward. It was alive! First, there had been juice—and in a week, there would be sugarcane “wine.” I tended the bottle through many rigorous days, of bus travel and shuttling luggage into hotel rooms and cycling over high passes with the bottle strapped to my pannier. Every few hours for days I gingerly loosened the cap to release the accumulating CO2, the telltale byproduct of sugar-to-ethanol fermentation (methanol, the dangerous form of alcohol that infamously makes people blind or kills them cannot be produced through fermentation). Finally, after five days, I lost my patience. The bottle had been falling off my bike every few hours for two days as I bumped along the dirt road between Cuenca and Santiago de Mendez, in the low Amazon basin. The juice was still fermenting, but I was ready to drink. I gave the bottle an hour in my hotel room so that the mucky sediments could settle to the bottom, then drank. The stuff was a grapefruit yellow now, with a bready, yeasty smell and a flavor reminiscent of raw, green cane juice but less sweet and with the obvious bite of alcohol. I had done it—connected the dots and found the missing link. Or, that is, I had made it myself.

The author discusses fermentation techniques with brewmaster Pedro Molina outside his brewpub, La Compania Microcervezeria, in Cuenca. Photo by Nathan Resnick.

Quick Cane Trivia

- Sugarcane is native to Southeast Asia.

- Consisting of several species, sugarcane is generally a tropical plant but is grown in Spain, some 37 degrees from the Equator.

- Sugarcane yields more calories per land surface area than any other crop.

- Sugarcane first arrived in the New World with Christopher Columbus on his second voyage across the Atlantic, when he sailed to the West Indies in 1493.

From left to right, five different products derived from sugarcane: fresh juice, juice fermenting with baker’s yeast, chicha de hongos tibicos, cane vinegar and punta, or distilled cane alcohol. Photo by Alastair Bland.

Other Local Wines to Taste in Ecuador

If you should visit Vilcabamba and have any interest in wine and fermentation, spend 20 minutes in a small store and tasting bar called Vinos y Licores Vilcabamba. The shop specializes in locally made fruit wines—including grape, blackberry and papaya. The shop also sells liquors made using cane alcohol and a variety of products, like peach and cacao. Most of the wines here are sweet or semi-sweet—and you can put up with that, go in, meet owner Alonzo Reyes and enjoy a tasting. He may even take you to the rear of the facility and show you the fermenting tanks, containing more than 5,000 liters of wines, as well as the cellar, where scores of three- and five-gallon glass jugs contain maturing wines.

Alonzo Reyes, owner of Vinos y Licores Vilcabamba, stands among his many jugs of fruit wines maturing in a small storage space. Photo by Alastair Bland.

The Name of a Dog

I must concede that I spoke a few days too soon in last week’s post about troublesome dogs in Ecuador and the owners that sometimes neglect them. I joked about the unlikelihood that a scruffy street mutt down here might be named Rex, Fido or Max. Well, 11 kilometers south of Sucua on the Amazonian Highway E-45, a dog came trotting out to meet me in the road. Its owners called it back. Its name? Max.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)