Your Next Favorite European Wine Region Isn’t in France, Italy or Spain

The wine in this country is so good, they don’t want to export it — keeping 98% for themselves

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/e5/b0e5627a-9d9b-4679-8198-61c19f8ddbf7/lake-geneva-switzerland-swisswines0518.jpg)

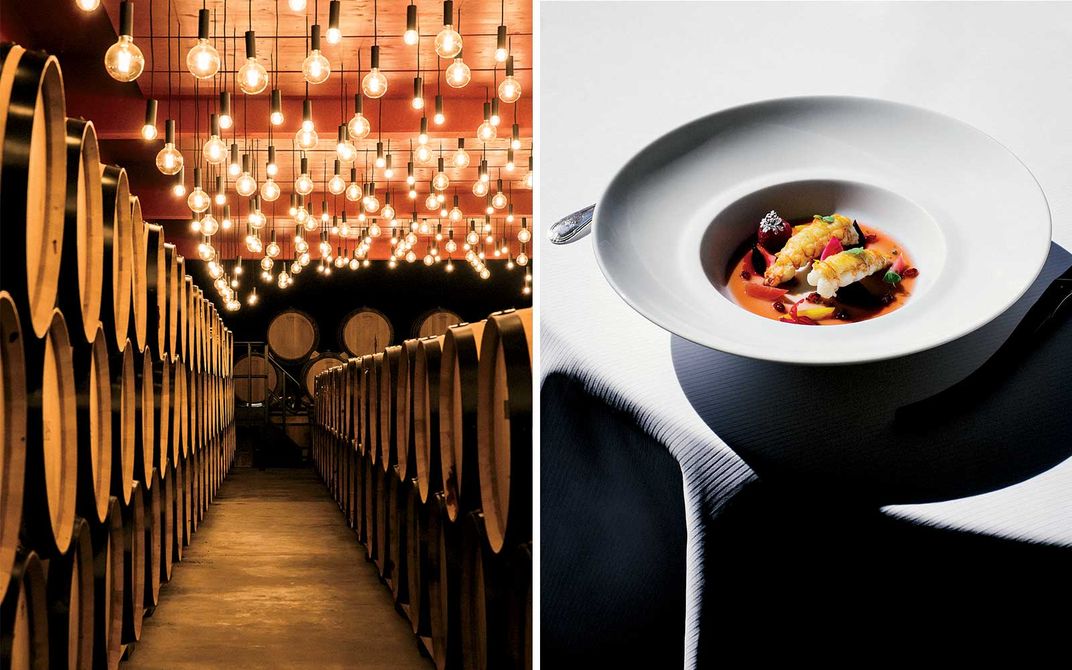

The Beau-Rivage Palace hotel in Lausanne, on the shores of Lake Geneva, maintains one of Europe’s great wine cellars. Earlier in the day I’d made my way through it, a maze of 80,000 bottles extending all the way under the tennis courts, with sommelier Thibaut Panas. The cool underground rooms held the usual suspects—grand cru Burgundies, first-growth Bordeaux, Barolos—as well as plenty of fine Swiss wines. It was one of the latter that I was drinking now, as I sat on the terrace at Anne-Sophie Pic, the acclaimed French chef’s namesake restaurant at the hotel: a glass of 2007 Les Frères Dubois Dézaley-Marsens Grand Cru de la Tour Vase no. 4. A Chasselas from the terraced vineyards of the Lavaux wine region, just outside the city, the white wine was rich, complex, and subtly spicy all at once. And it was exactly why I’d come to Switzerland, since there was little chance I would ever find it back home in the U.S.

The Beau-Rivage was built on the Swiss side of the lake in 1861, and it’s what a grand old European hotel should be, which is to say it keeps the feeling that you might at any moment drift into a black-and-white movie set between the wars. Its Belle Époque salons, ballrooms, and suites have played host to the likes of Charlie Chaplin, Coco Chanel, and countless others accustomed to grandeur and privilege. Case in point: the woman in red leather pants at the table next to mine, who was surreptitiously feeding morsels to her miniature dachshund. The dog would poke its snout out of her red leather handbag to receive bites of $85 duck, then disappear. It had manners. I drank my good Swiss wine, pondering the quirkiness of rich Europeans.

The reason you won’t find much Swiss wine in the U.S. is simply this: 98 percent of it stays in Switzerland, where it’s drunk quite contentedly by the Swiss, who are well aware that their wines are extremely good, even if the rest of the world is not. This situation isn’t entirely intentional. The wines are dauntingly expensive outside Swiss borders, and the fact that they’re made from unfamiliar native varieties doesn’t help, either. A $50 bottle of Swiss Chasselas would be a tough sell in your local American wine store.

That said, once you arrive within their borders, the Swiss are more than happy to share. Visiting wineries in Switzerland is actually easier than in many other European wine regions. Most have shops that double as tasting rooms and keep regular hours. Plus, Switzerland’s wine country, which includes the popular cantons of Vaud and Valais, is stare-around-you-in-awe beautiful.

All that is to say why, the day after my epic dinner, I was standing with Louis-Philippe Bovard on the Chemin des Grands Crus, a narrow road that winds among the ancient Lavaux vineyard terraces east of Lausanne, in the Vaud. Bovard is the 10th generation of his family to make wine here. “I have just a small piece of vineyard, which my father gave me, which the first Louis bought in 1684,” he said with the kind of casual modesty available to you when your family has been farming the same piece of land for almost 350 years. To our left, the green vines climbed in dramatic steps—some of the stone walls are 20 feet high—up to bare rock and, eventually, the Savoy Alps. Below us they dropped equally precipitously down to the ultramarine waters of Lake Geneva.

The Chemin des Grands Crus sees a lot of foot traffic these days, a consequence of the region’s having been named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2007. Bovard tolerates this with equanimity. “In September there will be a thousand people on the route,” he said. “They get very annoyed when they have to move aside for my car! But harvest is harvest. The work has to be done. And the winemakers are the ones who built the road, after all.” To give perspective, Bovard’s winery is located in the nearby town of Cully, whose population tops out at 1,800 or so. “And the other villages around here aren’t even this big, maybe three hundred inhabitants,” he added. “But of those, ten to twenty will be winegrowers.” The Dézaley Grand Cru area, which we were standing in the midst of and from which Bovard makes one of his best wines, is a tiny 135 acres, but more than 60 different families farm it.

The principal grape of Lavaux and of the Vaud as a whole is Chasselas. At one extreme it makes light, delicate, floral whites; at the other, rich, supple, full-bodied ones. “In its variety of expression, it’s like Burgundy,” Bovard told me later as we sampled wines in his tiny tasting room. “Chasselas from one cru to the next can be as different as Chablis is from Montrachet.” All of Bovard’s wines are impressive, but the standout was a 2007 Domaine Louis Bovard Médinette Dézaley Grand Cru, his top wine, its youthful fruit notes now shifting toward a layered toastiness. “As the wine ages you have less white flowers, more dried apricots, honey—much like a white Hermitage but just a bit lighter.”

I was exposed to Chasselas’s chameleonic range of styles again during lunch at Auberge de l’Onde, in the tiny town of St.-Saphorin on the old road from Geneva to the Valais. The green-shuttered, 17th-century building has been an inn for most of its existence, but these days it is known mostly for its restaurant. The feel in the downstairs brasserie is homey: wooden chairs, white-painted ceiling beams, white flowers in the window boxes. (The upstairs rotisserie is more formal, and open only for dinner.) As maître d’ and sommelier Jérôme Aké Béda seated us, a young guy carrying a motorcycle helmet poked his head through a window, and he and Aké chatted in French. “He’s a winemaker, a local guy,” Aké explained. “He makes a special cuvée for me, about three hundred bottles.”

Aké’s magnetic personality and extraordinary wine knowledge are this restaurant’s secret weapons. He’s also quick to note his unlikely path in life: “I’m from the Ivory Coast. I was raised on pineapple juice, not wine! But now I’m in wine because I love it. I swim in wine.”

If not for a chance meeting, Aké might still be living in Abidjan, the largest city in the Ivory Coast. In 1988, when he was the maître d’ at Wafou, one of the city’s top restaurants, he went to France on vacation and ran into one of his former professors from hospitality school. They chatted for a while, and eventually the man asked if Aké might like to be on the team for a project of his—in Switzerland. By 1989, Aké had a new life in a very different country. But it wasn’t until the mid 90s, working at acclaimed chef Denis Martin’s restaurant in Vevey, on Lake Geneva, that he fell in love with wine. He began training as a sommelier and, in a remarkable ascent, by 2003 had been named the best sommelier in French-speaking Switzerland by the Swiss Association of Professional Sommeliers.

Now he’s found his home at Auberge de l’Onde. “Chaplin, Stravinsky, Edith Piaf, Audrey Hepburn, they all came here,” he told me. But it was when he started to talk about Chasselas, not famous people, that he became truly passionate: “I have wines from everywhere in my cellar, but I’m going to talk to you about Swiss wine. And Chasselas—it’s one of the great grapes of the world. When you drink it, you feel refreshed. And it’s so subtle, so sensitive, you must read between its lines.”

Right as I was beginning to wonder if I’d wandered into a novel about the Chasselas whisperer, Aké set down plates of perch from the lake and expertly spit-roasted chicken in tarragon sauce. To go with them he poured us tastes from seven different bottles, all Chasselas. Some were bright, citrusy, and crisp; some were creamy, with flavors more reminiscent of pears. Of the two older vintages we tried, one had honeyed notes, the other a nutty flavor suggesting mushrooms and brown butter. “Chasselas...it’s also very earthy,” Aké went on. “It needs salt and pepper to bring out its amplitude.”

The following day I headed west in the direction of Geneva to La Côte, another of the Vaud’s six wine regions, to meet Raymond Paccot of Paccot-Domaine La Colombe. Here the land was less abrupt, the vineyards flowing down toward the lake in gentle slopes. Paccot’s winery was in Féchy, a rural village. Above it, higher on the hillside, was Féchy’s aptly nicknamed sister town, Super-Féchy, “where Phil Collins lives,” Paccot explained. “The rich people.” Even in less celebrity-filled Féchy, the local castle was currently for sale for $36.8 million, Paccot told me. “With a very nice view of the lake, if you’re interested.”

Rather than buy the castle, I ended up at La Colombe’s little shop and tasting room. Paccot, one of the first vintners in Switzerland to farm biodynamically, makes a broad range of wines, both red and white—Chasselas is not the only grape grown here. He set out an abundance of charcuterie and cheeses, and surrounded by bottles, we chatted about the history of the region.

As with essentially every European appellation, it was the Romans who cultivated vines here first. Later, in the 10th or 11th century, Cistercian monks established their own vineyards. Lavaux’s spectacular terrace walls were erected in the 1400s by northern Italian masons. By then the Vaud was part of the French-speaking Duchy of Savoy; that was also, Paccot told me, around the time when his family received its coat of arms, which features a dove (la colombe), a symbol of peace, and of course the winery. “It was given to us by Amédée, one of the Savoy counts, because in 1355, my ancestor helped secure peace. Plus, it was easier to give him a coat of arms than to pay him.” Through Europe’s many wars, vignerons grew grapes and made wine here. In French-speaking Switzerland you find local whites like Chasselas, Petite Arvine, Amigne, and Humagne, together with French transplants such as Marsanne (here known as Ermitage) and Pinot Gris (here known as Malvoisie). In the eastern, German-speaking regions, reds are more popular, particularly Pinot Noir (often referred to as Blauburgunder); in Italian-speaking Ticino, Merlot dominates.

Paccot’s 2014 Amédée, primarily made from the Savagnin grape, was a standout among the wines we tasted—melony and earthy, full-bodied but brightened by fresh acidity. “With Chasselas, it’s the delicacy, the lift, the fruit,” he said after taking a sip. “But with Savagnin it’s more like a mushroom. It smells the way it does when you’re walking in the forest.”

That comment came back to me the next day when I was, in fact, walking in a forest. But I was in the Valais, a very different place. If the Vaud is defined by the openness of Lake Geneva, Valais is defined by mountains. It’s essentially a vast gorge carved by the Rhône glacier, which before it began its retreat some 10,000 years ago stretched for nearly 185 miles and was, according to Gilles Besse, the winemaker I was walking with, “more than a mile deep. But what it left behind was this extraordinary mosaic of rocks. The soil in the Valais changes every fifteen yards—it’s not like Bordeaux.”

Nor, except for that mosaic-like soil structure, is it much like the Vaud. Here, the Alps towered up on either side of me, jagged and stunning. The previous day I’d had a conversation with Louis-Philippe Bovard and a Swiss wine-collector acquaintance of mine, Toby Barbey, about the difference between the Vaud and the Valais. Bovard had said, “The Valais, well, the soils are very different, the climate is very different, it’s very dry.” At this point Barbey interjected, “And the people are very different! They’re lunatics over there.”

I told Besse this and he laughed. He is trim, in his forties, with the requisite interesting eyewear and expensive watch that all Swiss men are apparently issued at birth. An accomplished skier, he’d recently completed the Patrouille des Glaciers, a frigid, all-night, cross-country-ski race covering some 70 miles from Zermatt to Verbier. Proof enough of a lunatic streak for me.

His family’s winery, Domaine Jean-René Germanier, opened for business in Vetroz in 1886. But at the moment we were deep in the precipitous Val d’Hérens. The forest we’d walked through gave way to one of his prized vineyards, Clos de la Couta. It is absurdly steep—your average mountain goat would be daunted. But somehow Besse harvests grapes from it, and very good ones at that. His peppery, nectarine-scented 2015 Clos de la Couta Heida (the local name for Savagnin), which we tried later on, was sublime. He also informed me that Val d’Hérens’s true fame comes less from its grapes than its fighting cows.

“Fighting cows?”

“Of course! Really angry animals. A top cow might sell for eighty-five thousand dollars, you know.”

“Not like a bullfight, right?”

“No, the cows fight each other. It’s to determine the queen—which lady rules the herd. There are many fights, but the finale is in Aproz in June. It’s a very big event. People come from all over Switzerland.”

Visual confirmation would have helped me wrap my brain around the concept. But for dinner we did indulge in an equally Valaisian tradition, raclette, at the ultimate destination for it, the Château de Villa, in Sierre.

It’s easy to look at raclette and think, “Well, that’s melted cheese on a plate.” And yes, raclette is basically melted cheese on a plate. But sit outside at Château de Villa on a spring night, looking at the turreted tower and white walls of this 16th-century building, and order the dinner tasting of five different cheeses from five different alpages (high mountain pastures) throughout the Valais. You will realize it’s much more than that.

At Château de Villa, the raclette master slices great wheels of Raclette de Valais AOC cheese in half, mounts them on metal racks, and positions them just close enough to a fire that the edge of the cheese crisps and the center melts without burning. He then scrapes the molten cheese onto a plate with a single stroke. Some cheeses are more earthy, some more oily, some more floral. All are distinct. After you try all five, you can have more of whichever you prefer, along with “light” accompaniments: boiled potatoes, bread, and pickles. And ask for the pepper mill. The correct amount of pepper? That, Besse told me, is a matter of debate.

The next day I took the train to Zurich, because of a new rule I’ve decided to apply to my life: if someone offers to show you vineyards from a speedboat, always say yes.

The someone in this case was Hermann Schwarzenbach, the debonair owner of Schwarzenbach Weinbau, a few miles south of the official city limits in the town of Meilen. Zurich’s not really known as a wine region—the city itself is too dominant, with its focus on international business and the arts—and as the villages on the northern shore of Lake Zurich have been absorbed into its sprawl, the historic line between what’s urban and rural has blurred. But the vineyards are still there, semi-hidden. Schwarzenbach pointed them out from the water—dozens of one-acre parcels up and down the lake, tucked in between stands of old plane trees, riverside parks, and the gabled summer homes of rich Zurichers. “Most of them are on land that’s protected against development,” he noted. “Otherwise they wouldn’t be there anymore.”

After zooming up and down the lake several times, we parked the boat in Schwarzenbach’s boathouse and repaired to lunch in the garden at a local restaurant, Wirtschaft zur Burg, to taste his wines. Though the building dates back to the mid 1600s, chef Turi Thoma is known for his lightly modernized takes on traditional Swiss dishes—pike from the lake simply roasted but served with a poppy, lime, and chile butter, for instance. Thoma, a compact, bald fellow with an impish smile, also buys all the wine for the restaurant. He joined us to taste Schwarzenbach’s 2008 Meilener Pinot Noir Selection. Pinot Noir is a more significant and increasingly popular red grape in German-speaking Switzerland than in the French areas, and the wine was a revelation—full of black tea and spice, intense dried-cherry fruit, juicy acidity. “You can really see the similarities to a great Côte de Nuits,” Thoma said. “You like the food?”

“Great!” I said. “Brilliant.” He was giving me that intent look that chefs give you when they feel like you might be politely hiding your actual opinion, so I ate another bite of the venison course we were on for emphasis. “And fantastic with the wine, too.”

“Great!” I said. “Brilliant.” He was giving me that intent look that chefs give you when they feel like you might be politely hiding your actual opinion, so I ate another bite of the venison course we were on for emphasis. “And fantastic with the wine, too.”

“Good,” he said, leaning back.

I said I was surprised to find Pinot Noir—and very good Pinot Noir at that—by the shores of Lake Zurich. “Yes,” Schwarzenbach said thoughtfully. “But think about it. The tradition of Pinot Noir here is over four hundred years old. Perhaps even longer. It was always our main variety of red wine. Classic cool-climate reds, that’s what we do. Yes, it was brought here by the...oh, the duke of whatever. But it’s our variety. Right?”

Exploring Swiss Wine Country

The cantons of Vaud, Valais, and Zurich offer all the pleasures of the world’s best-known wine destinations without the crowds. Give yourself a week to experience all three, along with the urban pleasures of Geneva.

Getting There and Around

Swiss International Air Lines offers 73 flights per week from Canada and the U.S. to Geneva and Zurich. To get between cities by train, invest in a Swiss Travel Pass. Though you can visit most wineries and tasting rooms unannounced, a good option is to work with a tour company like CountryBred, which plans dinners with winemakers, luxury transportation, tastings, and more.

The Vaud

To explore the wine regions of the Vaud, stay in the city of Lausanne. The recently renovated Beau-Rivage Palace (doubles from $565), originally built in 1861, has spectacular views over Lake Geneva, both from its exquisitely appointed rooms and from chef Anne-Sophie Pic’s namesake Michelin two-starred restaurant. A walk along the Lavaux terraces’ Chemin des Grands Crus, just 15 minutes from Lausanne, is not to be missed. Then visit Domaine Bovard, in Cully, one of the region’s benchmark Chasselas producers. Domaine du Daley, founded in 1392, is in Lutry. Its terrace has the best view of all the Lavaux wineries. Closer to Geneva in La Côte, Raymond Paccot’s Paccot-Domaine La Colombe is another highlight. Make sure to try the three Chasselas bottlings — Bayel, Brez, and Petit Clos — all from different terroirs. I loved dining at Auberge de l’Onde (entrées $13–$41), in St.-Saphorin, where sommelier Jérôme Aké Béda preaches the gospel of Swiss wine and the rotisserie-grilled meats are incomparable.

The Valais

Hotel-Restaurant Didier de Courten (doubles from $240), in Sierre, is a pleasant, relaxed base for your excursions. Thirty minutes away in Ardon, Domaine Jean-René Germanier is known as one of the Valais’s best producers, both of whites such as Fendant (as Chasselas is known in the region) and reds such as Syrah. Twenty minutes southwest brings you to Gérald Besse’s brand-new winery outside Martigny. Taste his impressive wines, such as the Ermitage Vielle Vigne Les Serpentines, from a vineyard planted on a dramatic 55-degree slope. Cheese-and-wine fanatics should try Château de Villa (entrées $11–$55), in Sierre, not only for the raclette tasting but also for the attached shop, which stocks some 650 different wines.

Zurich and Its Environs

Staying in Zurich gives you access to all the attractions of the big city, but just outside lie wineries that produce lovely whites and surprisingly good Pinot Noirs. In Zurich, the Baur au Lac (doubles from $926) is one of the great historic hotels of Europe, built in 1844 — the same year its founder, Johannes Baur, started his wine business, which the hotel still runs. At Schwarzenbach Weinbau, a wine producer 15 minutes away in the town of Meilen, you can sip subtle Pinot Noirs and citrus-apricoty white Rauschlings, available nowhere else on earth. Dinner at Wirtschaft zur Burg (entrées $15–$30), also in Meilen, is excellent. Chef Turi Thoma relies on ingredients such as pike and hare for his brilliantly executed spins on traditional recipes.

Other articles from Travel + Leisure:

- Hawaii's Kilauea Volcano Is Causing Earthquakes After Shooting Out 'Ballistic Blocks' Three Times Larger Than Bowling Balls

- Your Airline Seat Could Soon Be Able to Disinfect Itself and Give You a Massage

- You Can Play With Adorable Cats All Day on This Hawaiian Island

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.